Further inside the mysteries of St. Basil's

Moscow. Cathedral of the Intercession on the Moat (St. Basil's). South view. February 20, 1972.

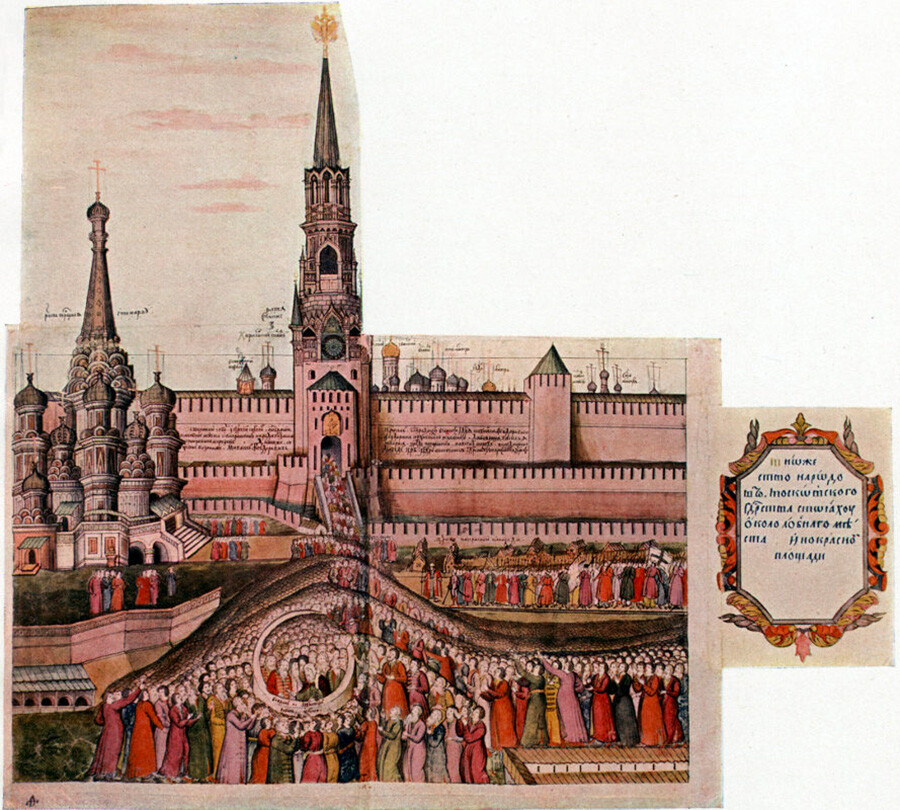

William BrumfieldAlthough Russian chemist and photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky is best known for his photographs of the Russian Empire in the early 20th century, he also established a business that produced color postcards and illustrations in books. Among the publications with his color photographs was a large volume published in 1913 on the occasion of the tercentenary of the Romanov dynasty. The illustrations included his reproduction of a tinted watercolor made for an album presented in 1673 to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in commemoration of the enthronement of his father, Mikhail Fedorovich, the first Romanov tsar.

Red Square. Proclamation of Enthronement of Tsar Michael Romanov. From left: St. Basil's, Lobnoye Mesto, Kremlin wall & Savior (Spassky) Tower. Reproduction of 1673 tinted engraving published in P. G. Vasenko, Romanov Boyars and the Enthronement of Mikhail Fedorovich (St. Petersburg, 1913).

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyThe watercolor purports to show the solemn occasion on February 21, 1613 when the people swore fealty to the newly chosen Tsar Mikhail on Red Square. The main architectural feature of the watercolor is the multi-domed St. Basil's Cathedral. Despite its fame, the complex structure continues to pose riddles. Even its name varies: from the popularly accepted “St. Basil’s” to its formal designation as the Cathedral of the Intercession on the Moat. In the 17th century it was also referred to as “Jerusalem.”

Having photographed this consummate landmark for decades, I was able in 2012 to re-photograph the interior with a digital camera.

Monument to Muscovy and Orthodoxy

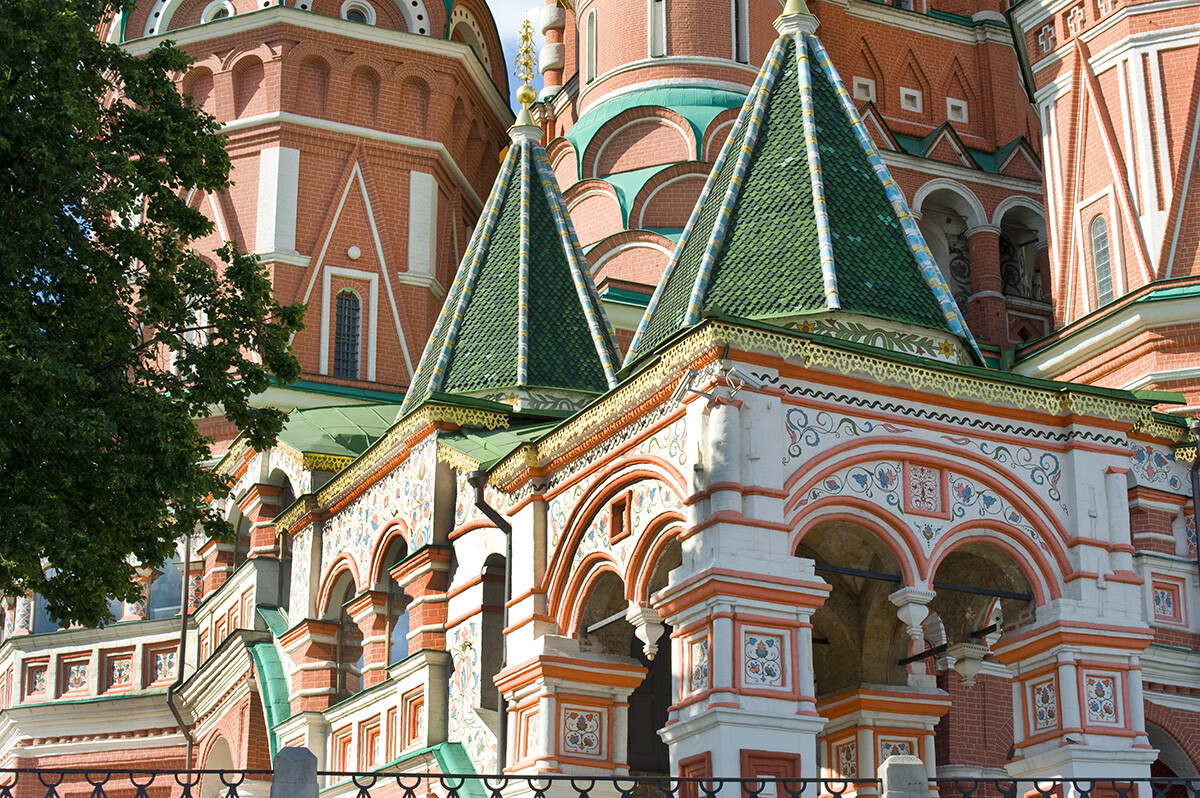

St. Basil's. Southwest entry stairway. May 26, 2012.

William BrumfieldSt. Basil's is located on high ground above the left bank of the Moscow River and provides a visual landmark over a large space known since the middle of the 17th century as Red (or "beautiful") Square. The church accordingly served as a symbolic link between the Kremlin, the center of political power, and the posad, the densely settled mercantile area in Kitay-Gorod. The origins of St. Basil’s are as complex as its form. Soon after Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible) captured the city of Kazan on October 1-2, 1552, he commanded that a church dedicated to the Holy Trinity be erected on the square outside the Kremlin at the Frolov Gate.

St. Basil's, interior. Southwest entry stairway. June 21, 1994.

William BrumfieldIvan intended to rebuild that church on a scale reflecting the importance of his defeat of Kazan, which not only eliminated a troublesome relic of Mongol power, but also opened a vast area for colonization and trade. Although the temple might seem a chaotic agglomeration of parts, its architects – generally recognized as Ivan Barma and Postnik Yakovlev – created a logical plan with a wealth of layered meaning.

Left: St. Basil's. Church of St. Varlaam Khutinsky, southwest view. May 26, 2012. Right: St. Basil's. Church of St. Varlaam Khutinsky. Interior with icon screen. June 2, 2012.

William BrumfieldThe new construction had a dual purpose – to express the triumph of Orthodoxy and of Muscovy. Ivan’s victories were not simply an episode in interminable border warfare, but a defining event in the identity of a nation endowed with a sense of destiny.

To celebrate these ideas, each component of the cathedral was endowed with iconographic and symbolic meanings. Composed of churches grouped around a central tower, this monument has served as a symbol of unifying power since its completion in the mid-16th century.

St. Basil's. Church of the Intercession, south portal. June 2, 2012.

William BrumfieldThe Intercession Cathedral ensemble (St. Basil’s) consists of a central tower surrounded by eight free-standing churches on a common terrace that was enclosed and painted in the 17th century. The plan of the ensemble embodies the trinitarian concept: each axis, diagonal and side has three towers, and the structure on the terrace level is divided into three parts.

On the interior, the plan creates an enchanting maze of decorated portals and low passageways that link the compact towers of the individual churches. Each of these spaces can accommodate only a few worshippers, and services at the temple complex were often held outdoors on an adjacent part of Red Square.

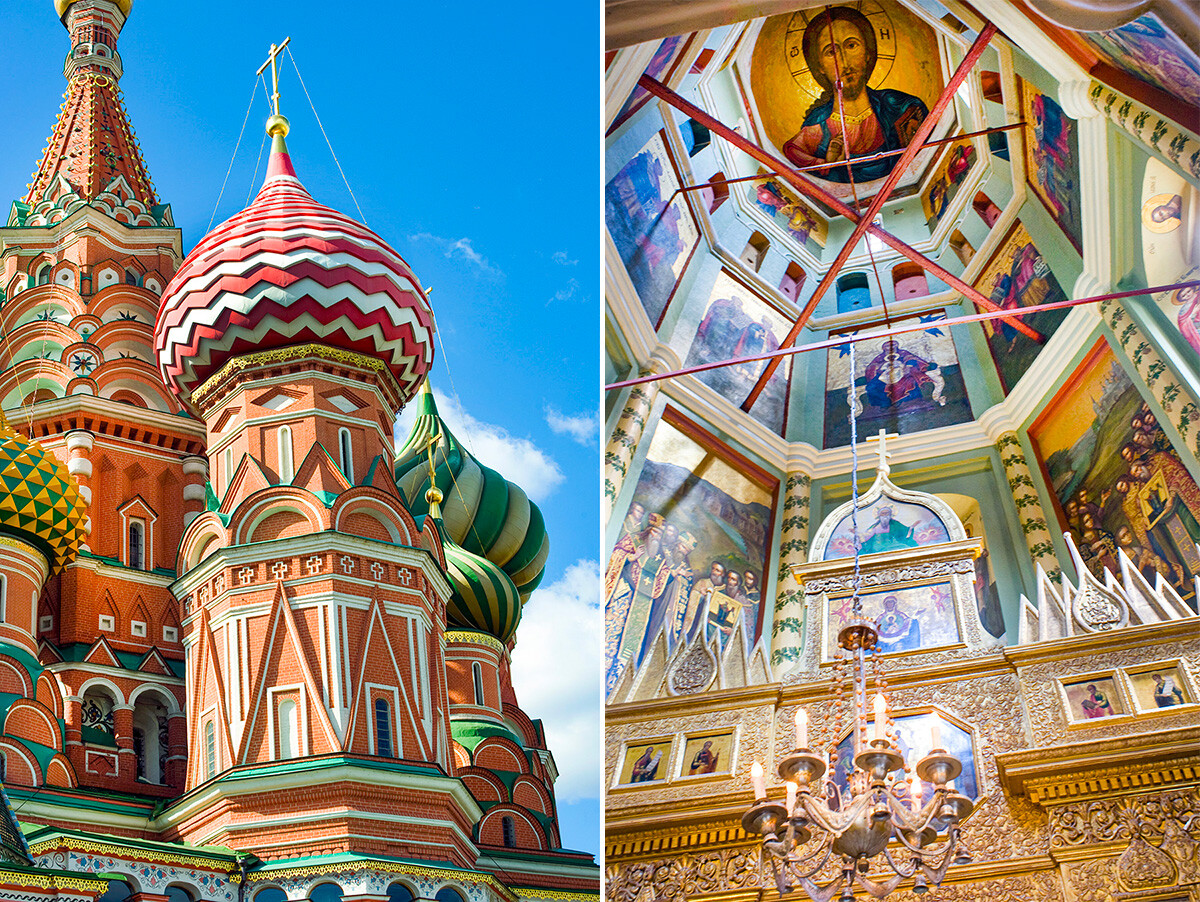

Left: St. Basil's. Church of the Velikoretsky Icon of St. Nicholas, southwest view. May 26, 2012. Right: St. Basil's. Church of the Velikoretsky Icon of St. Nicholas, interior. View of tower with upper tier of icon screen. June 2, 2012

William BrumfieldMy preceding article examined the five tower churches on the west, center, and north together with the connection. This one will survey the remaining five, including the small shrine that was dedicated to Basil himself.

An exploration of the interior begins with the main entrance gallery, located on the west side with flanking stairways (capped with pitched roofs that leads to the elevated terrace connecting the component churches. Originally open, the terrace was enclosed during a renovation of the ensemble in the 1680s. Although tightly constrained, the gallery has a festive appearance with elaborate decorative motifs painted in phases during the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Honoring family

St. Basil's. Church of St. Nicholas Velikoretsky, interior. View of upper tower & dome with image of Christ Pantocrator. June 2, 2012

William BrumfieldTwo churches on the south flank relate to Ivan and his family. The dedication of the southwest church to St. Varlaam of the Khutynskii Monastery near Novgorod commemorates

Ivan's father, Basil III, who shortly before his death assumed the traditional role of monk and adopted the name Varlaam. The tower interior is of unadorned, whitewashed brick. The small, exquisite icon screen was renovated in the 18th century, yet the icons show an earlier style.

St. Basil's. Church of St. Nicholas Velikoretsky, interior. Image of Christ Pantocrator. June 2, 2012.

William BrumfieldThe south church (one of the four major towers at the points of the compass) is dedicated to the icon of St. Nicholas of Velikoretsk, a “wonder-working” icon brought to Moscow from the village of Velikoretskoe (near Vyatka) at Ivan’s command in 1555. Originally placed in the Dormition Cathedral, many miracles were attributed to the icon. It also can be seen as having a dual symbolic reference to the River Velikaya near the ancient city of Pskov, whose monks played a role in articulating the mission of Muscovite authority.

St. Basil's, interior. South gallery passage with 18th-century wall paintings. Left: painting of St. Catherine. June 2, 2012.

William BrumfieldLike the interior of the north tower, the interior of the St. Nicholas Church was lavishly repainted with religious images in the mid-19th century. The culminating point is a youthful image of Christ Pantocrator on the dome vault. The icon screen was renovated in the mid 19th century.

Walls like brick

Left: St. Basil's. Church of St. Alexander of Svir, southwest view. August 5, 1994. Rigth: St. Basil's. Church of St. Alexander of Svir, interior. View of tower with upper tier of icon screen. June 2, 2012.

William BrumfieldThe southeast church, dedicated to St. Alexander of Svir, commemorates the Russian victory on August 30 over Tatar cavalry led by Prince Yepancha, thus eliminating a major threat to Moscow’s hold at the siege of Kazan. St. Alexander (1448-1533) was a monastic leader active in the Novgorod diocese and know for his rigorous asceticism. In 1485, he laid the foundation of what became the Alexander Svirsky Monastery, near the Svir River.

St. Basil's. Church of St. Alexander of Svir, interior. View of tower with painted bricks. June 2, 2012.

William BrumfieldAlexander was canonized during Ivan’s reign at the initiative of Metropolitan Macarius. St. Alexander’s feastday occurs on August 30, and thus both the northeast Church of the Three Patriarchs and the southeast church symbolize the Russian victory on that day.

Although not painted with religious images, the walls of this small tower are a fascinating example of a technique known as pod kirpichi (“like brick”) in which the walls were painted brick red, with white seams limned to resemble mortar. This practice, imported from Italy, was also applied to the brick exterior of the entire ensemble in the late 18th century. The paint not only protected the walls from moisture seepage, but also enhanced the color of the surface.

St. Basil's, interior. South gallery passage with 18th-century wall paintings. From left: St. Catherine, St. Sergius of Radonezh, Metropolitan Peter. June 2, 2012.

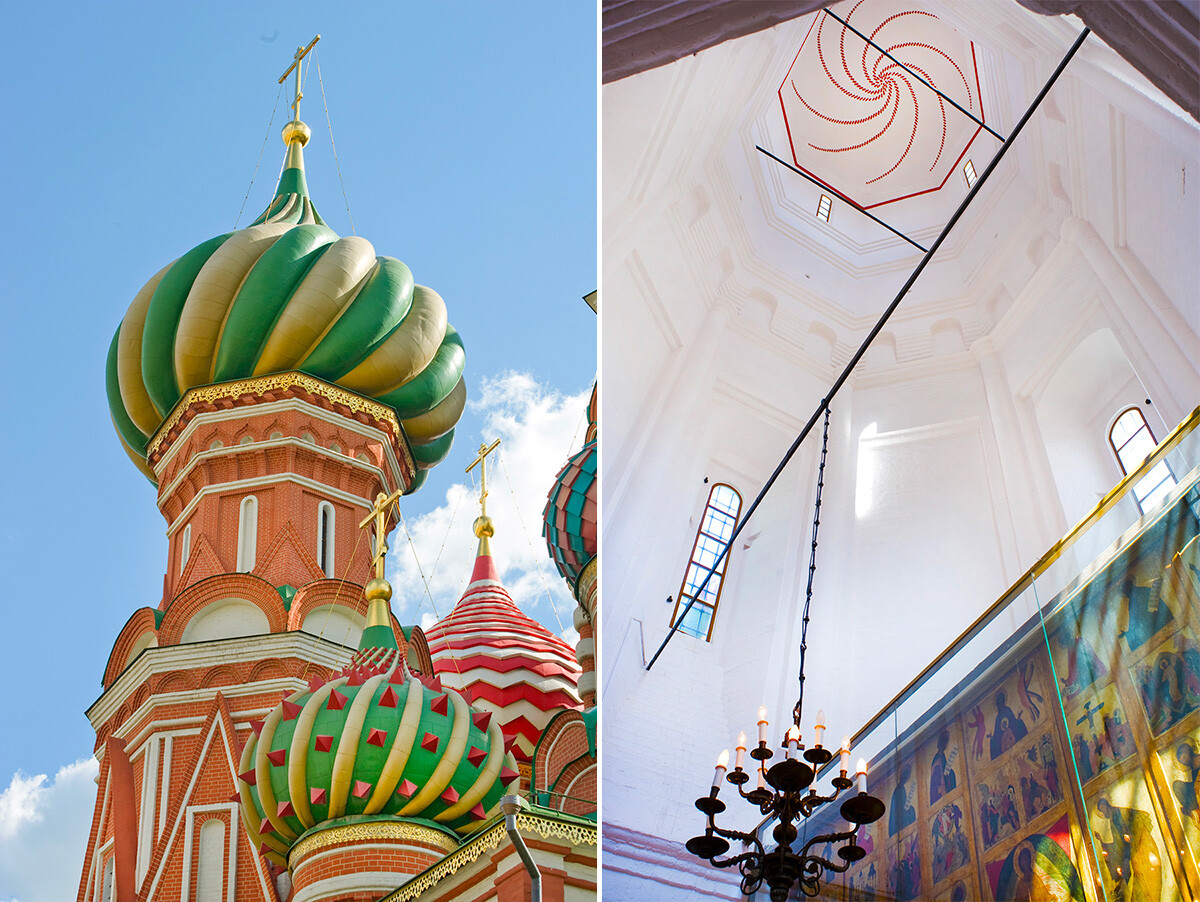

William BrumfieldThe main axis concludes on its eastern end with the major tower dedicated to the Trinity. This church is the holy of holies for the ensemble by virtue of its dedication to the trinitarian concept, which forms the numerological system of the cathedral. The sole decorative element on the whitewashed interior walls is a brick spiral on the vault of the dome. The icon screen was renovated in the 18th century.

Why St. Basil’s?

Left: St. Basil's. Church of the Trinity, north view. Lower center: Dome of Church of Basil the Blessed. May 26, 2012. Right: St. Basil's. Church of the Trinity, interior. Tower with icon screen & decorative brick spiral in dome. June 2, 2012.

William BrumfieldWhen all the original churches are accounted for, there is still the popular name of the temple –St. Basil’s. Basil the Blessed (1469-1552 or 1557) was a Muscovite yurodivy — or "fool in Christ" — revered by the tsar himself as well as by the common people for his saintliness and gift of prophecy. With the support of Metropolitan Macarius, a wooden shrine in his honor of Basil (Vasily Blazhenny) was erected to the east of the original Trinity Church.

St. Basil's, northeast view. From left center: Trinity Church, Church of Basil the Blessed, Church of the Three Patriarchs (in shadow), Church of Sts. Cyprian & Justina. Background: Tower of Church of the Intercession. East view. August 6, 1987.

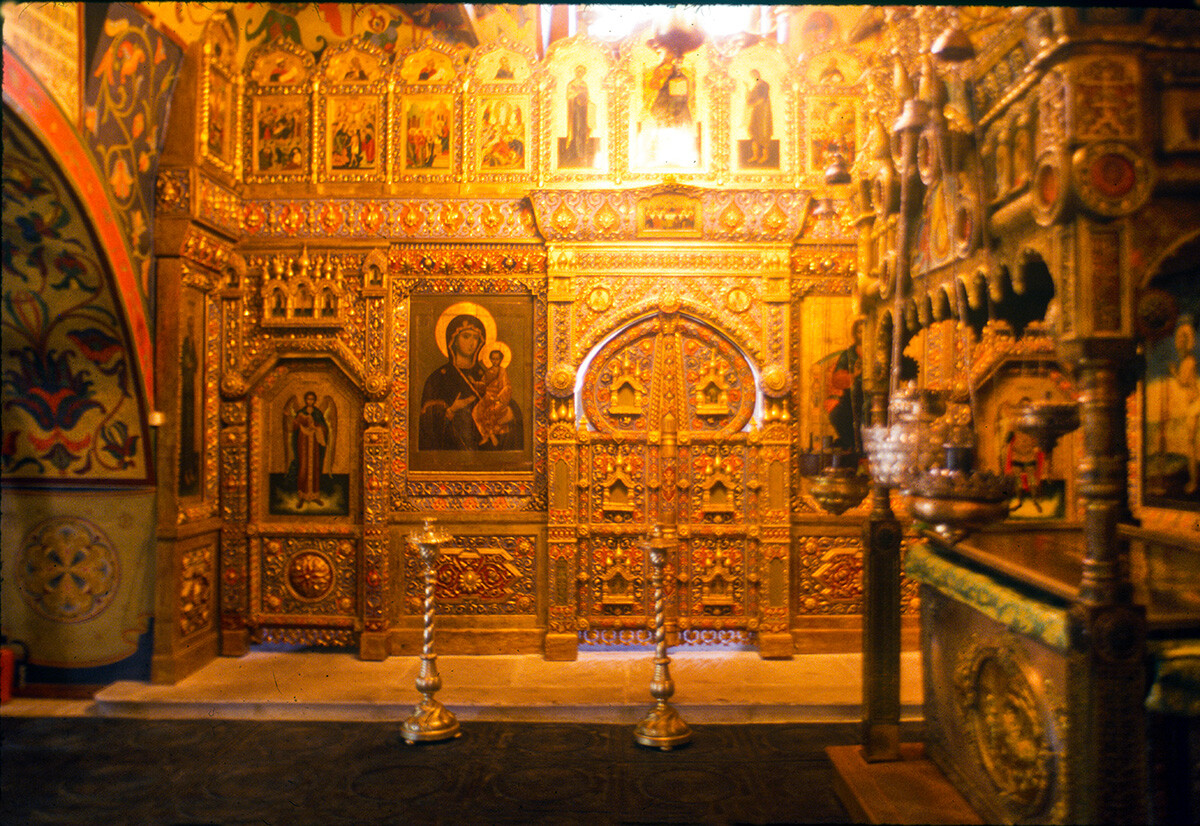

William BrumfieldThe shrine was maintained during the building of the Intercession Cathedral. Basil’s official veneration took place in 1588, during the reign of Ivan’s son Feodor and with the support of Boris Godunov). At that time, a small brick Church of Basil the Blessed was attached to the northeast corner of the cathedral. Renovated in 1672, its architecture retains archaic features of the 16th century. The small interior is dominated by a lavish icon screen and by the sarcophagus of Basil.

St. Basil's. Church of Basil the Blessed, interior. View east toward icon screen. Right: Sarcophagus of Basil the Blessed. June 21, 1994.

William BrumfieldThe Church of Basil the Blessed also became the resting place of another “fool in Christ,” Blessed John — popularly known as “the big cap” (Bolshoy kolpak) — who before his death in 1589 expressed the desire to be buried near Basil the Blessed.

Despite the modest size of the church in relation to the surrounding towers, the cult of Basil grew to usurp in common usage all the cathedral's previous designations, official or unofficial. Indeed, it was the only part of the ensemble that held liturgical services daily. Services at the other churches were held only on their dedicatory day and on the 12 major feastdays.

St. Basil's. Ground level passage to Church of Basil the Blessed. Ceiling painting of Nativity of the Virgin at Nativity Altar near grave of John the Blessed. June 21, 1994.

William BrumfieldMore could be written about the layers of symbolic richness displayed in St. Basil’s, a richness that has evolved over the centuries since its original construction. The Intercession Church itself has become an icon of Russia, a complement to the Kremlin as a statement of national identity.

St. Basil's. Ground level passage with display of construction artifacts & different layers of wall decoration from 16th- 19th centuries. June 21, 1994.

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century, the Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France where he was reunited with a large part of his collection of glass negatives, as well as 13 albums of contact prints. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox