What’s inside the Mitrokhin Archive, the largest leak of classified KGB files in history?

In the spring of 1992, a Russian man knocked on the doors of the UK Embassy in Riga, Latvia. From the bottom of his bag, he pulled out a sample of classified files he had allegedly smuggled out of the KGB archives in Russia. To the bewildered clerk, he promised more KGB documents in exchange for refuge in the UK.

An unannounced visitor

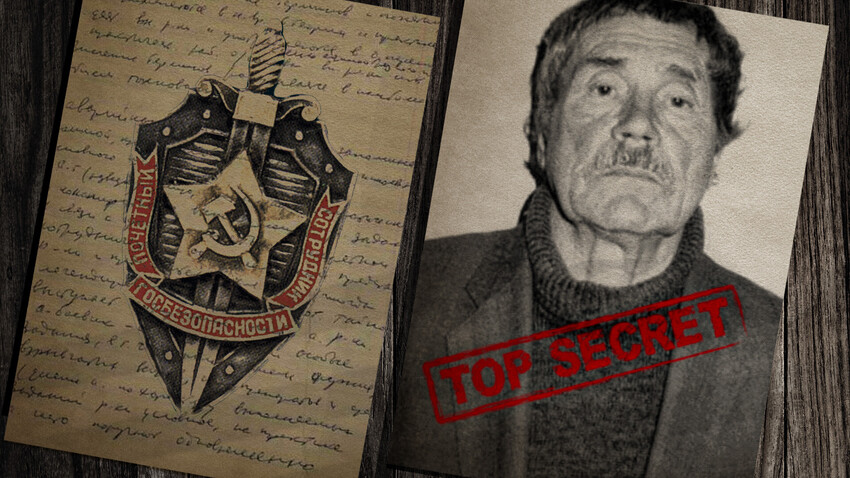

The man who showed up in the UK Embassy was Vasiliy Mitrokhin, a retired KGB officer. Not only was he retired, but he also claimed to represent an organization that no longer existed, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 had put an end to it. Nonetheless, the documents were of interest to foreign intelligence services, as they might have provided a unique insight into one of the most secretive organizations of the Cold War era.

The sample of documentation that Mitrokhin had brought to the UK Embassy indicated the man, indeed, had access to classified information and was likely to have more, as he had claimed. The UK Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) moved to exfiltrate the rest of the materials and their source from Russia.

A stash at a dacha

It turned out, back in the USSR, Vasiliy Mitrokhin had unparalleled access to the KGB archives, due to his position in the organization. As the KGB leadership ordered to relocate the archives of KGB’s First Main Directorate from the organization’s headquarter at Lubyanka to the new KGB complex in Yasenevo District in the South-West of Moscow, Mitrokhin, who worked as a senior archivist, was charged with overseeing the transfer.

For Mitrokhin, this proved an excellent opportunity to copy and smuggle tons of classified documents. From 1972 to 1984, the archivist copied hundreds of thousands of files which revealed how the KGB approached its intelligence-gathering operations and handled its extensive networks of spies abroad from the dawn of the Soviet era up to its final years.

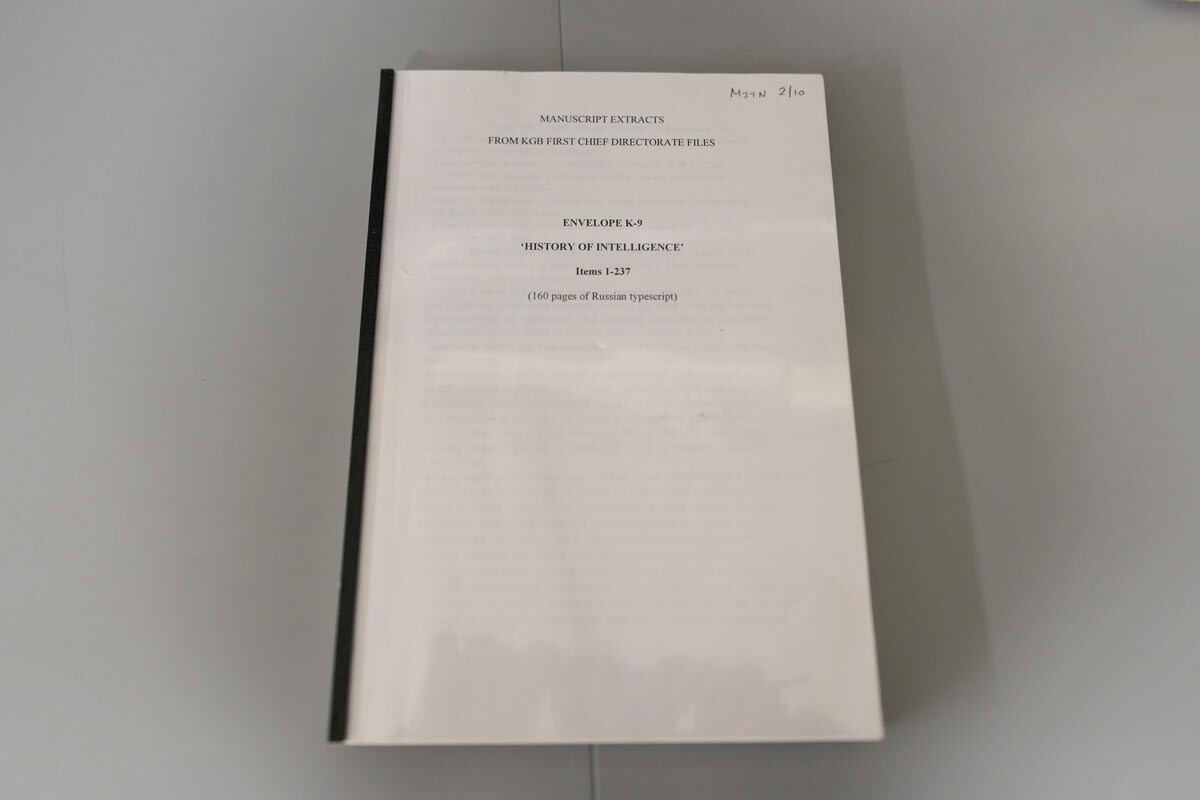

Boxes of the Mitrokhin Archive in Churchill Archives Centre.

Churchill Archives CentreFor years, Mitrokhin had been meticulously copying the secret documents stored in the KGB archives and quietly stashing them in a milk-churn buried below the floor at his dacha.

Curiously, he moved to reveal the contents of his stash only after the Soviet Union had collapsed in 1991. As a citizen of post-Soviet Russia, he traveled to now independent Latvia with a sample of documents. The staff at the U.S. Embassy which he had approached turned him down at first, as they thought he was an unreliable source, but the UK Embassy, along with MI6, proved far more eager.

“From those [first] 50 documents, the British realized what a huge importance Mitrokhin’s archive represented. After that, they arranged for Mitrokhin’s entire family to move to London: his wife, mother-in-law and son (they were all disabled). And he [Mitrokhin] was already in his 80s,” said Oleg Gordievsky, a notorious Soviet double-agent who defected to the UK in 1985.

Mitrokhin’s motivation remains a subject of heated debates. Some are convinced the former KGB officer was disenchanted by the Soviet system and indiscriminate methods its secret police used to suppress dissidents inside and abroad and was, thus, ready to take the gravest of risks, only to make sure the truth would eventually be exposed.

Others suspect the defector had ulterior motives: disappointed in how his career ended (in the archives and not in the field) and having been burdened with his relatives’ disabilities, Mitrokhin might have seen a window of opportunity for himself at the end of his life, skeptics say.

The contents

Regardless of the motives, the revelations were made. In its totality, the Mitrokhin Archive trumped any other intelligence that has even been obtained throughout the lifespan of the USSR. In the words of the FBI, the files were “the most complete and extensive intelligence ever received from any source”.

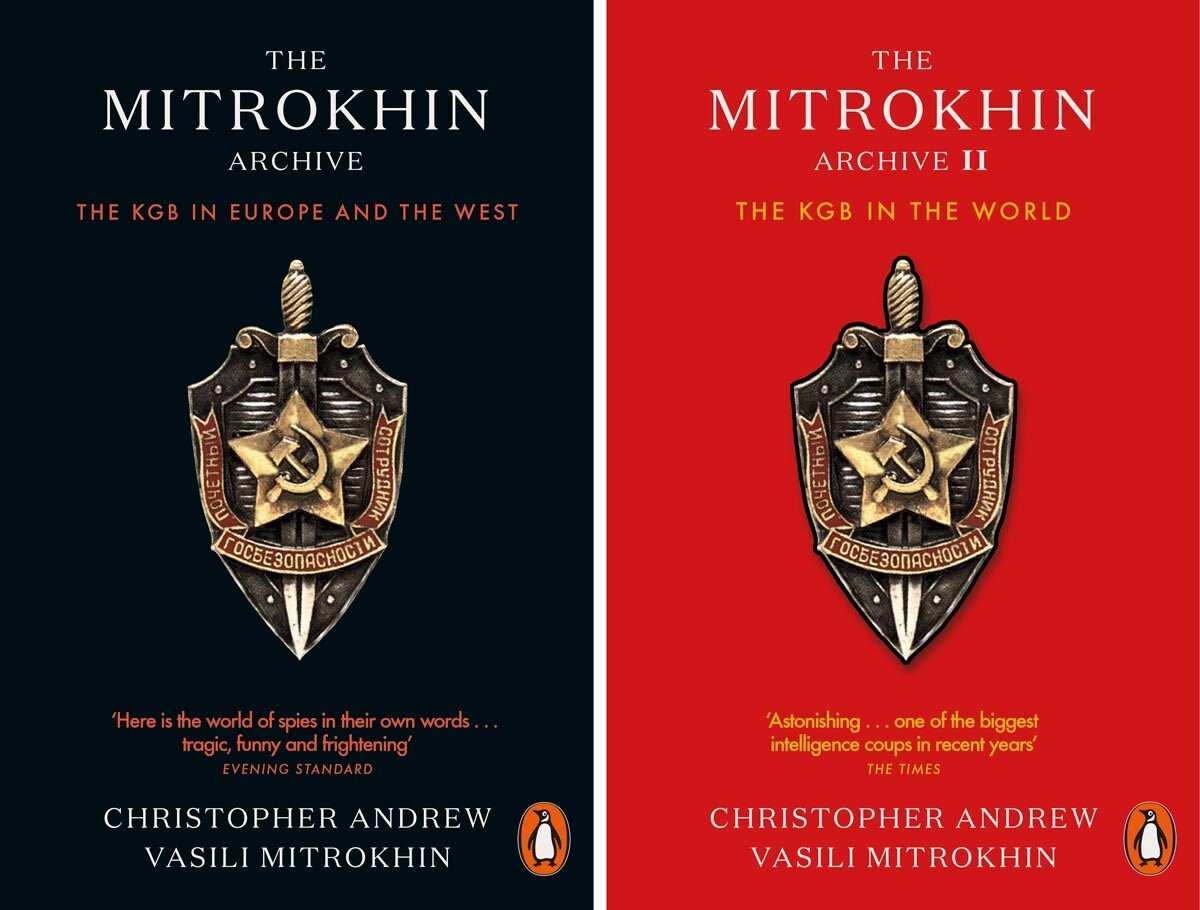

“The Mitrokhin files range in time from the immediate aftermath of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution to the eve of the Gorbachev era,” said Christopher Andrew, a professor of history who co-authored two books based on Mitrokhin’s documents.

The files were as extensive in scope as they were in the timespan. They included notes on Pope John Paul II, who the secret services sought to compromise; Melita Norwood, the KGB’s longest-serving UK agent, who has been passing classified scientific information to her Soviet handlers for four decades; the famous spy-ring in the UK known as the Cambridge Five, some of whom the KGB handlers considered unreliable, due to alcohol abuse; and Martin Luther King Jr., who the KGB aimed to discredit (ironically, along with the FBI), among other people.

In addition, the files also revealed certain things that were previously unknown by the authorities in the West. For example, they learned that the USSR had a plan to conduct a series of sabotage attacks on U.S. soil (and in other allied countries), in case the Cold War developed into open warfare. Stashes of arms were maintained in various parts of the country, ready to be used in the case of an armed conflict.

The archive also included information that the KGB supported conspiracy theories around the murder of President John F. Kennedy by funding writers who were promoting an alternative point of view on the historical event. Other disinformation operations — known as “active measures” in KGB terms — were also uncovered.

The fallout

Just as Mitrokhin’s motives are a subject of debates, so are the relevance and validity of the disclosed information. Although the files undoubtedly offered a rich source of information for historians, their relevance for modern intelligence services is doubted, chiefly because of how outdated they are.

The first book based on the Mitrokhin Archive was published in 1999 and the original notes were released for public research only in 2014. Even by the time of original disclosure of the files to the UK authorities in 1992, the Soviet Union, and the KGB, were already gone. Although the revelation of the notes prompted parliamentary inquiries in the UK, Italy and India, those did not produce any sensational results. Suffice it to say, for example, that Soviet informant Melita Norwood was never prosecuted in the UK for what she had done during the Cold War.

Today, anyone can access Mitrokhin’s files via the Wilson Center’s digital archive.

Click here to read about the NOTORIOUS Soviet defector who single-handedly sparked the Cold War.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox