Bracing for Internet blacklist?

Children in a math class participate in a “Virtual Classroom” pilot project. Source: Kirill Braga / RIA Novosti

{***Censorship or transparency?***}

Lawyers, legislators and Internet experts are divided on how amendments to the Internet law will be enforced – but most agree that law enforcement agencies can already block content deemed illegal. Amendments to the Federal Law on Protecting Children from Information Harmful to their Health and Development goes into effect Nov. 1.

Related :

Most Russians support censorship online

Pirate Party of Russia prepared to defend the Internet in case of censorship

The controversy is about whether the legislation will expand those powers – or, possibly, curtail them. And the ultimate fate of a controversial video, the “Innocence of Muslims,” will be a case in point.

Debates have raged for months since Russia’s parliament passed in July what became known as the Internet blacklist law, a series of amendments that would create a register of websites hosting “illegal content” – such as child pornography or the promotion of suicide or drug use.

Under the law, once a site has been listed on the register, the site’s provider would have 24 hours to demand that the owner remove the illegal content from the site. If the site’s owner refuses to do so, the provider would then have to block access to the site. The Russian State Agency on Press and Mass Communications has been placed in charge of the register.

Censorship or transparency?

The bill was widely feared to be part of a slew of legislative efforts to crack down on the opposition in wake of a series of massive anti-Kremlin protests that broke out in December of 2011. Following President Vladimir Putin’s inauguration in May 2012, Russia’s parliament passed a law increasing fines for unauthorized protest rallies, and another bill forcing NGOs with foreign funding to register as foreign agents.

The Internet blacklist law, as it was dubbed, was the third such bill – and drew a heated reaction from human rights activists and the opposition.

As the amendments were being debated in parliament in early July, the Presidential Human Rights Commission issued a statement calling the bill an attempt to introduce censorship, which is unconstitutional in Russia.

“The bill stipulates ‘collective responsibility’ in the Internet industry for criminals not tried by a court of law.... It thus stipulates the introduction of censorship in the Russian Internet segment,” it said, citing similar legislation that was discarded in the United States because of censorship concerns.

Fearing that the law, if passed, could apply to some articles on its site, the Russian sector of Wikipedia shut down in protest for a day in July, fueling the debate further.

A wave of September protests brought no new spate of arrests, and the controversy over the bill has become more nuanced. Media and Communications Minister, Nikolai Nikoforov, has sought to dispel fears of looming censorship, explaining that the law would bring transparency to existing practices.

“This law has no objective to introduce censorship or any sort of influence on media,” he said in interviews with Russian news agencies earlier last month.

Instead, Nikiforov admitted that various Internet sites are often arbitrarily blocked across the country. “The law would allow this process to be regulated somehow. Right now everything is chaotic – something or other is blocked here and there. This law would introduce a single set of rules,” he told ITAR-TASS.

According to Artem Tolkachev, a lawyer with the Tolkachev & Partners law firm, law enforcement agencies already have instruments to block Internet sites they fear are extremist – a concept that can also apply to political content.

“Personally, I support this law, and I find the mass hysteria that accompanied it isn’t completely justified,” Tolkachev said. “Of course there are risks that state organs will abuse their authority. But they already have all the powers to shut down sites as it is.”

{***Innocence of Muslims controversy***}

Innocence of Muslims controversy

One example is the recent controversy over the “Innocence of Muslims,” a trailer and video which sparked violent protests in the Arab world. Russian lawmakers have asked law enforcement authorities to check the clip for signs of extremism, but even with a court decision pending, reports appeared last month that access to YouTube was blocked in Omsk and Volgograd.

But under the new law, if the video is found extremist, it could jeopardize the entire YouTube domain in Russia.

“You may laugh at it but the whole of YouTube may be blocked in Russia completely over this video on November 3 to 5,” Nikiforov said in his Twitter blog on Sept. 18. A local court in Chechnya has already ruled that the video is extremist, meaning that YouTube, which is controlled by Google, would either have to block access in Russia, or face YouTube being blacklisted.

Google stated earlier this month it would agree to block the “Innocence of Muslims“ video pending a court notice, after a Moscow court found the content extremist. The company cited its own policy of blocking certain material in countries where it is found illegal.

Meanwhile, Alexei Mitrofanov, the new head of a parliamentary committee on information policy and technology, assured journalists that YouTube wasn’t going anywhere and that any solution to the video controversy would be “creative,” RIA Novosti reported recently.

{***Child welfare and extremism***}

Child welfare and extremism

Still, Tolkachev cites the Omsk and Volgograd incident as just one example of how access to Internet sites can already be blocked without a court ruling. “If there is an order from the Prosecutor General’s office to block a site, then clearly Internet providers react with fear.”

Given the ease with which law enforcement agencies can already block Internet sites, Tolkachev believes the new bill will make regulations more transparent – and make it difficult to arbitrarily shut down content.

“Right now, a site can be shut down if there’s a court ruling that finds it extremist,” Tolkachev said. “There’s also a quasi-legal method in which prosecutors issue a deposition, and those responsible must remove the content or close down the site. At least this law introduces a series of specific rules about this process that will be understood by everyone.”

The problem, Tolkachev said, is that how the new rules are enforced has yet to be worked out, so forecasting its repercussions on the media is very difficult.

But leaders in Russia’s burgeoning Internet industry argue the bill has far more problems besides the technicalities of enforcement.

“This law does not limit the powers of various law enforcement agencies to block sites,” Anton Nosik, an executive at Livejournal, said. “It just offers new procedures in addition to the ones that already exist. This law concerns the protection of children. But most current cases of sites being blocked or filtered is about content that’s deemed extremist. And there’s nothing in this law that will regulate how, exactly, content is recognized as extremist.”

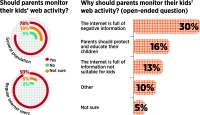

Compounding the problem are attitudes about censorship that are less than clear cut. While the Russian Constitution forbids censorship, a recent poll suggests that a majority of Russians support Internet censorship. Some 63 percent of respondents were in favor of censorship to block harmful content on the Internet.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox