Why a Greek city is home to the world's second biggest collection of Russian avant-garde art

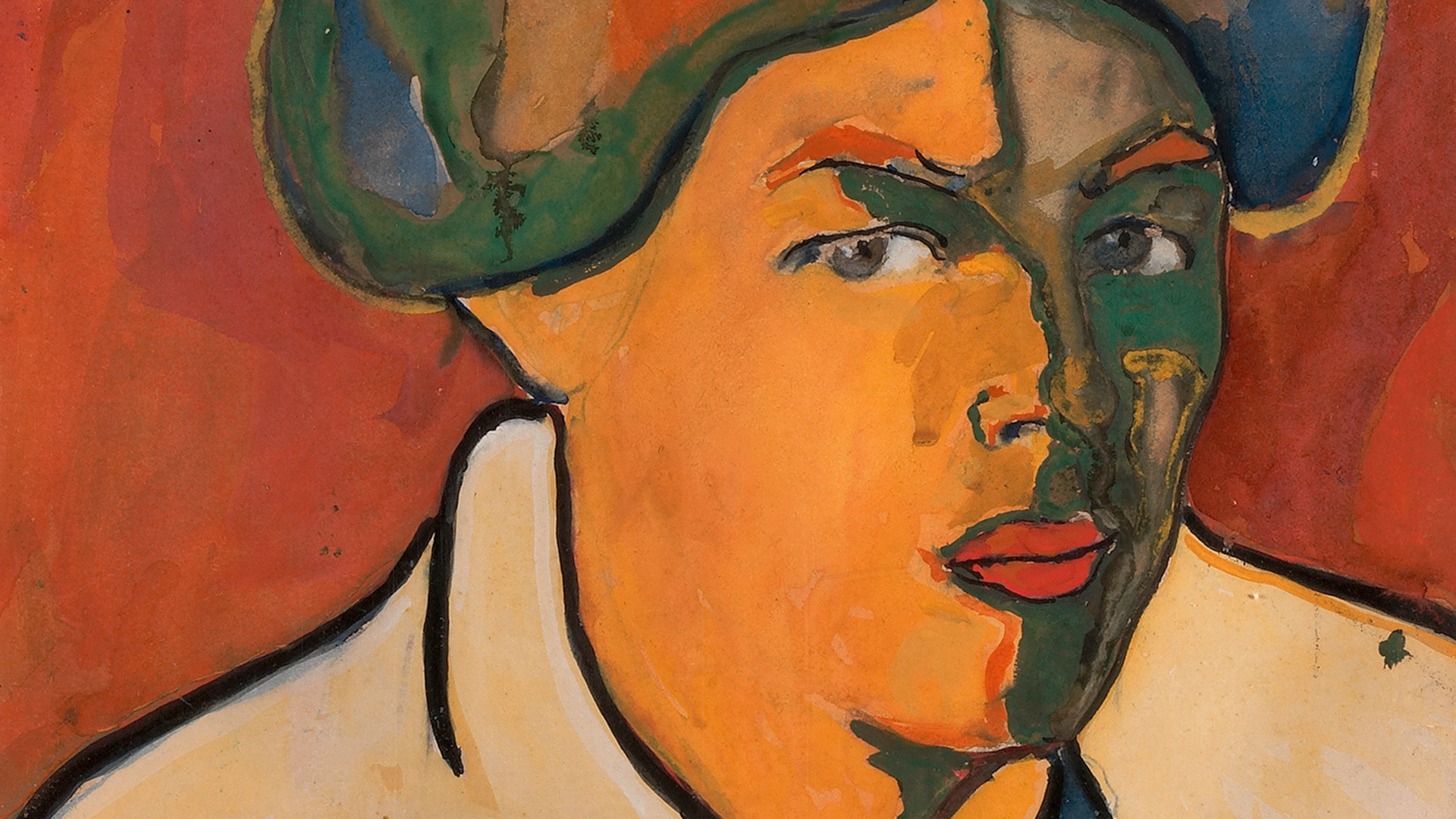

Kazimir Malevich. Woman's portrait, 1910-1911.

Press photoThe State Museum of Contemporary Art opened in Thessaloniki in 2002. The truly legendary collection of Russian avant-garde artists of the first half of the 20th century put together by George Costakis in Moscow after World War II formed the basis of the museum. Before that, works by Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, Alexander Rodchenko and Lyubov Popova from the 1,300 works collection, had already toured the USA. The show at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1981 is described as groundbreaking, and the tour also

Soviet deal

Russian art collector George Costakis (1913 - 1990), February 1973.

Getty Images

"In 1937 the avant-garde was consigned to oblivion - the USSR needed a new realism that could be understood by ordinary people. The reforms that were carried out pulled the plug on all that the avant-garde had achieved, and their works were buried deep inside the storerooms," says the director of the Thessaloniki museum, Maria Tsantsanoglou.

In addition to researching the actual phenomenon of the avant-garde, the indefatigable Costakis hunted down works of the artists of that period everywhere - from the apartments of the small number of collectors that then existed to the families of the artists who had been left their works after their deaths. For instance, he tracked down a work by Lyubov Popova, one of the "Amazons of the avant-garde", who had died in 1924, to her relatives' dacha - painted on plywood, it had been used as a window shutter.

According to accounts by contemporaries, almost all the works were on display, densely covering the walls of his apartment on Vernadsky Prospekt, which anyone with an interest in the avant-garde could come and view. In the 1970s Costakis even delivered talks about his collection at venues abroad, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Tsantsanoglou notes that when news of his collection spread around the world, foreign tourists in Moscow, when asked about the places they wanted to see, used to reply: "I want to visit the Kremlin, the Bolshoi Theater

Pavel Filonov. Head, mid-1920s.

Press photoWhen Costakis was diagnosed with cancer, he decided to move to Europe for treatment. He planned to take the collection numbering several thousand paintings, works of graphic art, sculptures and manuscripts with him, but no one would issue him with a permit to take out the collection which, although rejected by the authorities, were valuable for the history of the avant-garde. Under a "deal" with the Soviet government, he bequeathed over a third of the collection to the Tretyakov Gallery as a "gift". In return, he was allowed to take out those works which are today displayed in Thessaloniki and in temporary exhibitions throughout the world.

Russian avant-garde's Greek home

In 1997, seven years after the collector's death, the Greek government acquired the collection. It was displayed in the Thessaloniki museum, which opened five years later, alongside contemporary Greek and Russian art, and was also actively lent out for exhibition to U.S. and European museums. Now the institution has decided to "reboot" the museum, and with

"It is the only comprehensive collection of the Russian avant-garde to be found abroad and there is a wonderful opportunity now for its study and development, as well as the promotion of Russian culture in the West. It is always interesting when something that has been small in scope is given a big stage. The Russian avant-garde today is part of world culture - exhibitions take place throughout the world and foreign collectors understand this art and buy it," Krasnyanskaya told Russia Beyond.

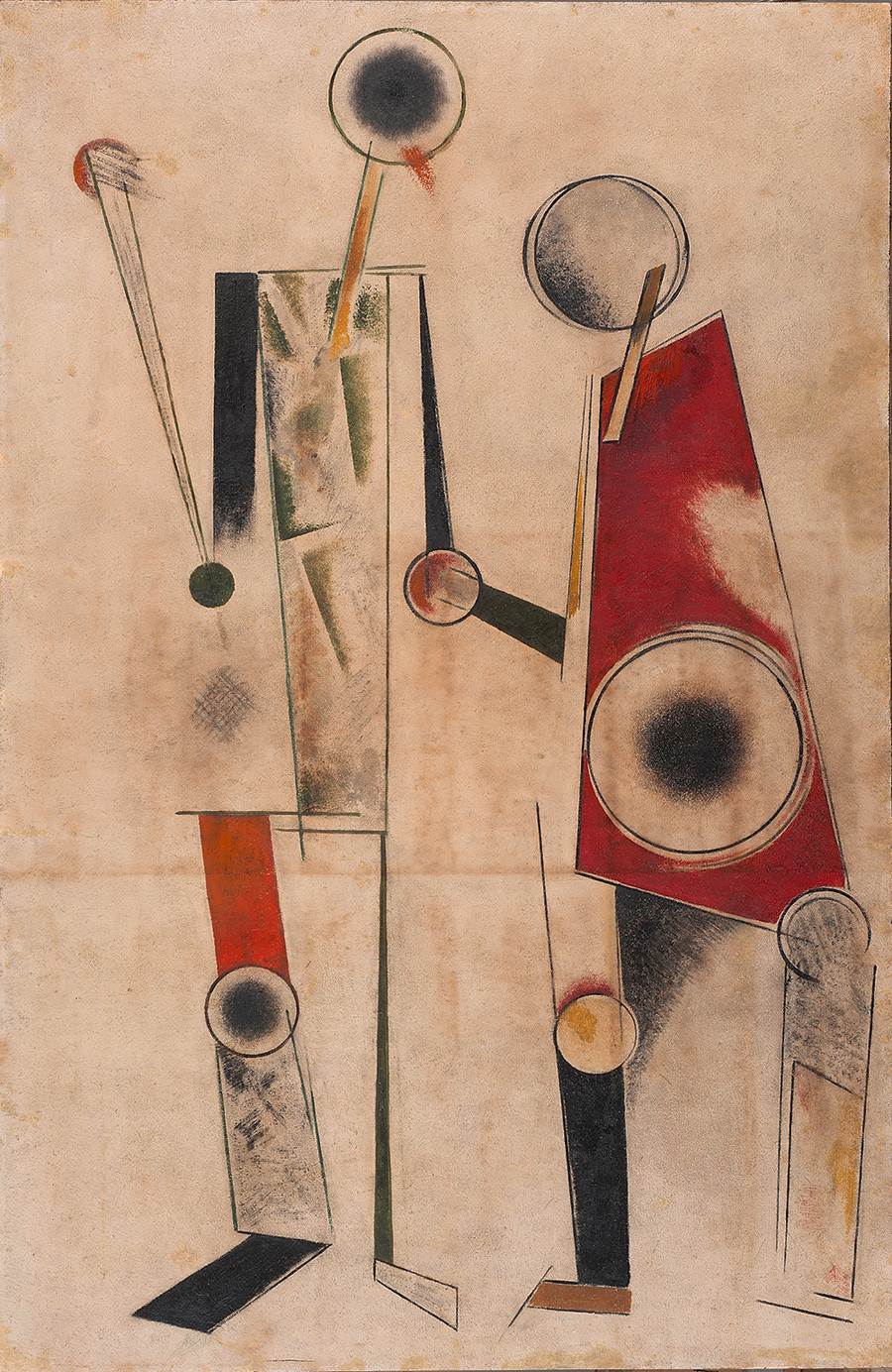

Alexander Rodchenko. Two figures, 1920.

Press photoA new exhibition opened in the museum on June 29 with the support of the Russian AVC Charity Foundation set up by Andrey Cheglakov. Titled "Thessaloniki. The Costakis Collection. A Restart", it is the first project inspired and organized by the committee. Well-known experts in the field of the avant-garde Alla Lukanova and Natalia Avtonomova were involved in curating it, and the design of the exhibition is also the work of architects from Russia.

Kazimir Malevich. Woman's portrait, 1910-1911.

Press photoThe display, as previously pledged by the museum, is absolutely accessible to every viewer and not only tells the story of Costakis himself, but also narrates the chronology of the development of the avant-garde in Russia: starting with the early years of the 20th century when Russian artists were influenced by European Modernism and found inspiration in folklore and continuing right up to the emergence of Cubo-Futurism and Suprematism and the avant-garde artists' links with the young Soviet state. Three floors of the museum are adorned with paintings, works of graphic art and porcelain by Malevich, Kandinsky, Popova, Rodchenko, Nikritin, Klyun

Aleksandr Drevin. Ship, 1931.

Press photoThe museum promises that exhibitions of this scope will be a permanent feature, with displays changing twice a year. "We intend to invite other world museums and private collectors to participate in our exhibitions," Krasnyanskaya says. And there is no shortage of potential invitations to send out - works of the Russian avant-garde are held today by all the major museums of the world, from the Pompidou Center in Paris and London's Tate Modern to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox