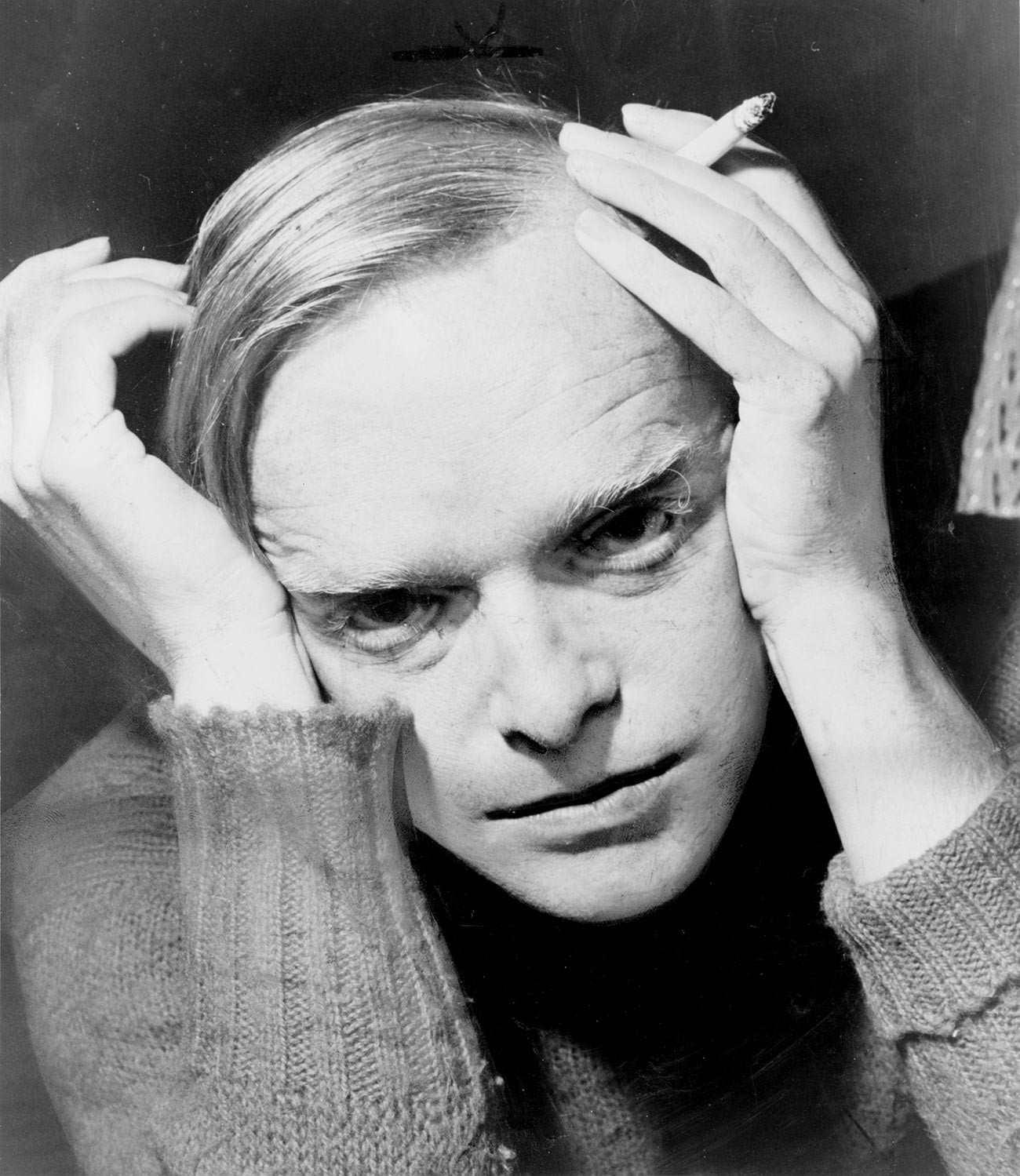

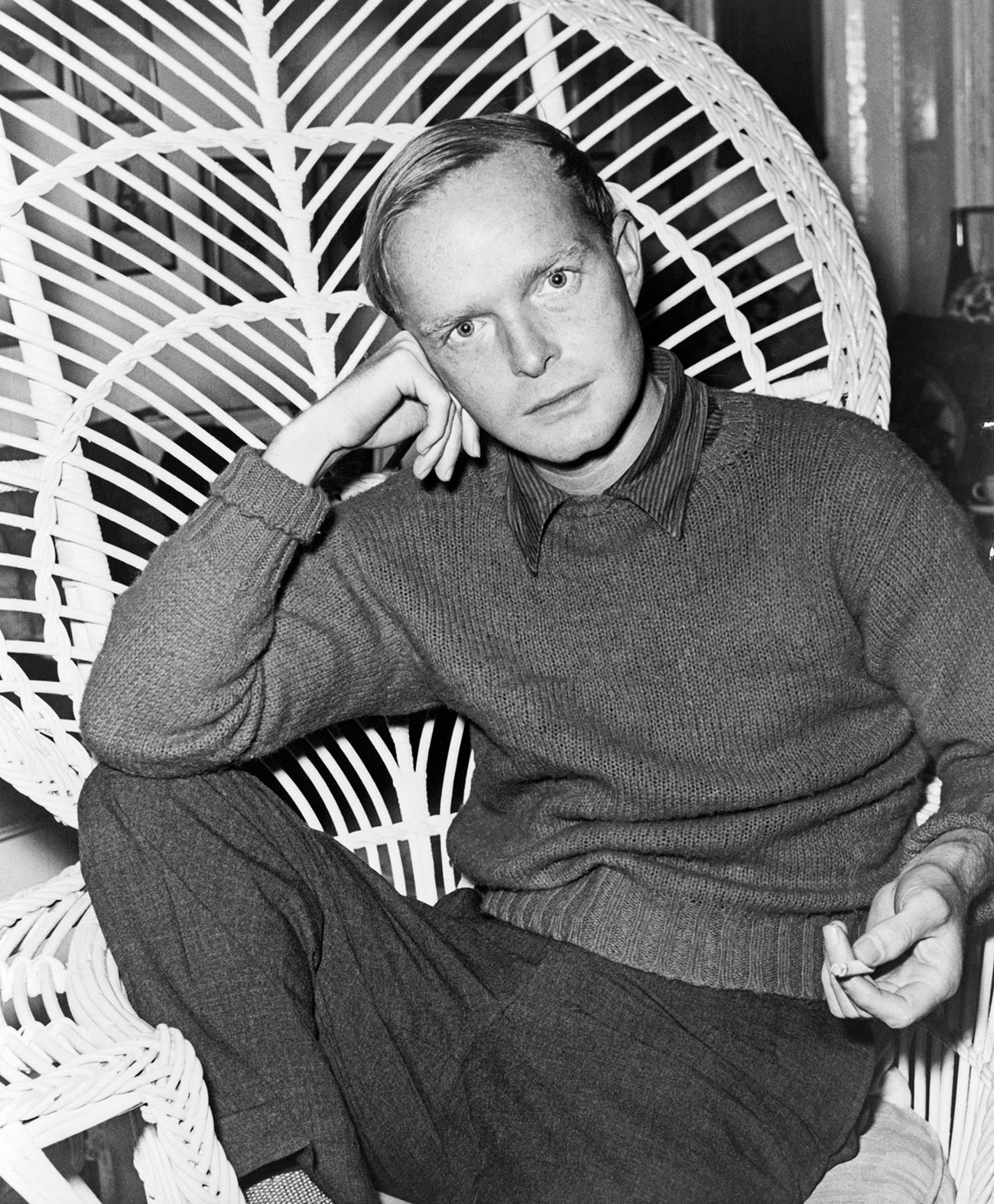

What Truman Capote saw behind the Iron Curtain

It sounded like a joke. In December 1955, in the midst of a Cold War, a group of African-American artists descended on the Soviet Union to give the first ever performance of George Gershwin’s folk opera ‘Porgy and Bess’ in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) and Moscow.

‘Porgy and Bess’ made a splash in Leningrad.

Yevgeny Khaldei/МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruIt was an incredible adventure. About one hundred people came, including the director, the crew, the cast, their children, friends, dogs and secretaries. Up-and-coming young writer Truman Capote, the author of ‘Other Voices, Other Rooms’, was among the group of journalists who came to cover the historic event. His report about the first trip he made behind the Iron Curtain later appeared in The New Yorker.

Capote’s visit to the USSR was eye-opening. It marked the first time a U.S. theater company had been to the Soviet Union since the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The Soviet premiere of ‘Porgy and Bess’ came at a time when the Cold War was showing no signs of abating. Nikolay Savchenko, one of the Soviet interpreters attached to the troupe by the country’s Ministry of Culture, kept repeating the following catchphrase over and over: “When the cannons are heard, the muses are silent; when the cannons are silent, the muses are heard.” That’s how Capote got the title for his book, ‘The Muses Are Heard’. Beautifully written, it was full of curious, occasionally ridiculous and implausible situations.

The 31-year-old writer described the Soviet Union with a Swiss watchmaker’s eye to detail. Back in those days, the USSR was deemed a closed, dangerous country that no one knew much about. Curious and open-minded, Capote, who was openly gay, described what he saw with genuine bewilderment and signature sarcasm.

Capote described the Soviet Union with a Swiss watchmaker’s eye to detail.

Boris Kosarev/Maria Kosarev's archive/russiainphoto.ruRisqué opera in the USSR

‘Porgy and Bess’ made a splash in Leningrad and Moscow, and grabbed headlines in the USSR. Capote gave the readers a behind-the-scenes look at the crew and their relations. The African-American singers performed all the famous songs from Gershwin’s opera, such as ‘Summertime’, ‘I’ve Got Plenty of Nothin’ and ‘A Woman Is a Sometime Thing’.

Two members of the troupe enjoying themselves in Moscow.

Getty ImagesThe sensual opera left Soviet Culture Ministry officials speechless. It was too late to wonder how on earth a musical play revolving around African-Americans (totally alien to the Soviet people) and touching upon sex, drugs and violence could ever premiere in the strait-laced, communist USSR.

First shock

Coming to the Soviet Union was more than a cultural shock. The troupe of The Everyman Opera singers and dancers boarded the Blue Express train in East Berlin and traveled for three days and nights before reaching the USSR in December 1955. Their train adventure was plagued by discomfort and inconvenience during the long-distance journey in the second-class sleepers. What a shock and disappointment it was when, instead of the stereotypical “truly Russian” duo of vodka and caviar, the American passengers were offered veal cutlets and broth.

READ MORE: 10 incredibly atmospheric PHOTOS of Soviet Leningrad

In Leningrad, the entire troupe checked in the landmark hotel Astoria. It wasn’t quite what they expected. “Some think it is the Ritz of all Russia. But it makes only a few concessions to Western ideas of a de-luxe establishment. Of these few, one is a room off the lobby that advertises itself as an Institut de Beauté, where guests may obtain Pédicure, Manicure and Coiffure pour Madame. The Institut, with its mottled whiteness, its painful appurtenances, resembles a charity clinic supervised by not too sanitary nurses. There is also on the main floor a trio of restaurants, one leading into another — cavernous affairs, cheerful as airplane hangars,” Capote wrote. His rich and raw descriptions would have won him the among TripAdvisor review readers.

“The bathroom adjoining the third-floor room assigned to me had peeling sulphur-colored walls, a cold radiator and a broken toilet that rumbled like a mountain brook. The tub itself, circa 1900, was splotched with rust stains and the water that poured from the taps was brown as iodine, but it was hot, it made a wonderful steam…”

The bitterly cold Russian winter brought the need for warm clothes. But shopping lists mostly remained empty, due to the extortionate dollar-to-ruble exchange rates. “But, man, that ice cream costs a dollar a lick. And guess what they want for a little bitty piece of chocolate not as big as your toe? Five-fifty,” Capote wrote.

The bitterly cold Russian winter brought the need for warm clothes.

Viktor Akhlomov/МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruStepping outside of the hotel the writer, hungry for story, was appalled when he came across several men beating up a stranger near the St. Isaac’s Cathedral. “Four men in black had a fifth man backed against the cathedral wall. They were pounding him with their fists, hitting him with the full weight of their bodies, like football players practicing on a dummy. A woman, respectably dressed and carrying a pocketbook tucked under one arm, stood on the sidelines as though she were casually waiting while some men’s friends finished a business conversation. Except for the cawing of the crows, it was like an episode from a silent movie; no one made a sound and as the four attackers relinquished their hold on the man, who fell and lay spread-eagled on the snow, they glanced at me indifferently, then joined the woman and walked off, still without a word.” Could a similar scene happen somewhere in the United States, where youth crime skyrocketed in the 1950s? Capote chose not to draw any parallels.

He fearlessly visited restaurants and bars in the company of certain Stefan Orlov, a married guy who spoke fluent English and had a crush on a blond bombshell who was part of the U.S. group. Orlov showed Capote around town and grew angry when the writer failed to keep pace with him in terms of drinking vodka. So, Orlov took Capote to a place whose atmosphere would be fit for a Chuck Palahniuk novel.

Capote fearlessly visited restaurants and bars in the USSR.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.“It was like falling into a bear pit. The body heat and beery breath and damp-fur smell of a hundred growling, quarrelling, jostling customers filled the brightly lit café. Eight or ten men huddled around each of the dozen tables. The only women present were three waitresses — all of them brawny girls, wide as they were tall, and with faces round and flat as plates. In addition to waiting on tables, they did duty as bouncers. Calmly, expertly, with an odd absence of rancor and less effort than it takes to yawn, they would throw a punch that knocked the stuffing out of a man double their size. Lord help the man who fought back. If he did, all three girls would converge on him, beat him to his knees and then literally wipe the floor with him as they dragged his carcass to the door and pitched it into the night.”

Capote soon discovered that he was followed in the streets of the city by a man in dark glasses in what sounded like a scene from a spy movie. Perhaps, that’s called the writer’s imagination.

READ MORE: A Cold War SEX SCANDAL that involved a Soviet Spy and a toppled British politician

“I noticed that there was one man who showed up every time among the onlookers, yet did not seem one of them. He always stood at the rear — a chunky man with a crooked nose, bundled in a black coat and astrakhan cap, with half his face hidden behind the kind of windshield dark glasses that skiers wear.”

Moscow saga

Following the performances in Leningrad, Capote and the behemoth troupe of ‘Porgy and Bess’ actors left for Moscow.

The troop 'Porgy And Bess' In Moscow.

Getty ImagesThere, he met a bunch of youngsters born with a silver spoon in their mouth, mainly the sons of artists, scientists and diplomats. This encounter had a strong impact on Capote. In the late 1950s, he started writing another report for The New Yorker. It focused on the gilded youth, whom Capote broadly described as the “sons and daughters of the Russian revolution”. To gather material and meet people and put flesh on the bones of his story, Capote returned to the USSR two more times, in 1958 and 1959.

READ MORE: Top 15 foreign celebrities who visited the USSR (PHOTOS)

Like an investigative journalist, he gathered enough material to pen a decent story. Capote’s profile of the Moscow elite was initially called ‘A Daughter of the Russian Revolution’ and put the spotlight on the 20-year-old ringleader of the Moscow glitterati. Capote had written around 40 pages when, in the summer of 1959, he informed William Shawn, who edited The New Yorker for a third of a century, that he couldn’t finish the story.

Capote’s visit to the USSR in the 1950s was eye-opening.

Legion MediaCapote said he was afraid for the lives of those mentioned in his article. They could be easily identified by Soviet secret police and sent into exile in Siberia, or even worse. What could be worse than leaving his readers without a book? Perhaps, Capote simply lost interest in solving the Soviet puzzle and found a noble excuse to move forward. His next bestseller, ‘In Cold Blood’, made waves in 1966. It was a true account of the murders of the Clutter family in 1959 Kansas.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox