Unraveling the cult behind Russia’s ‘Brat’ franchise

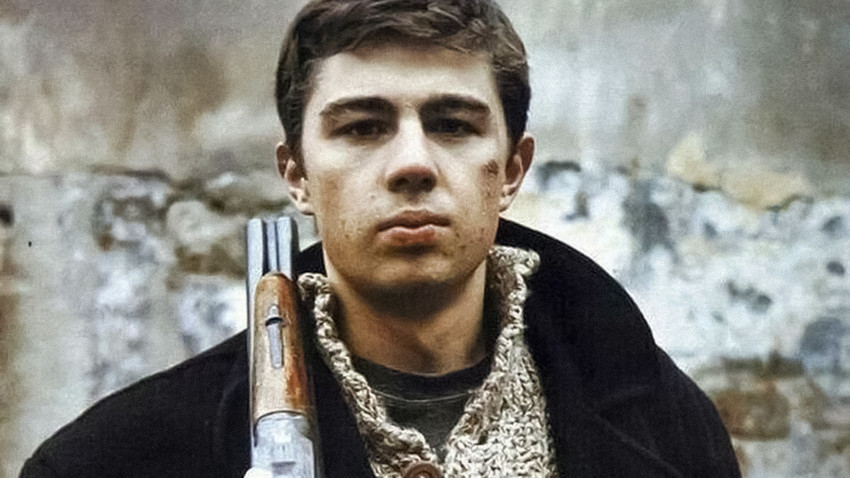

Sergei Bodrov Jr. in 'Brat'.

Aleksei Balabanov/CTB Film Company, 1997Both movies - Brat (‘Brother’, 1997) and its follow-up Brat 2 (‘Brother 2’, 2000) - became knockout cult hits in Russia. What makes Balabanov’s franchise really special is that it also serves as a bridge to understanding the Russian culture and the post-Soviet generation of the 1990s.

Danila Bagrov portrayed by ‘Prisoner of the Caucasus’ star Sergei Bodrov, Jr.

Aleksei Balabanov/CTB Film Company, 1997Although he majored in foreign languages, Balabanov was sort of a natural-born director. Cinema was more than just his métier. It was a way to experience and relive life on a deeper level. Balabanov had a pitch-perfect ear for dialogue, rhythm, striking detail and character interaction. In the early 1980s, he served in the Soviet army’s transport aviation and flew to Afghanistan during the war to bring back the bodies of the dead.

READ MORE: What was the Soviet war in Afghanistan like? (PHOTOS)

[SPOILERS AHEAD]

In ‘Brother’, young and green-behind-the-ears Danila Bagrov (portrayed by ‘Prisoner of the Caucasus’ star Sergei Bodrov, Jr.) returns to his small provincial town after his army service. Danila’s mother begs her son to visit his older brother (Viktor Sukhorukov), who she thinks is a big boss in St. Petersburg. In reality, Viktor (nicknamed Tatar) is a hit man and is in big trouble. To defend his brother’s interests above ethics, Danila takes up a gun and eventually his brother’s position.

The younger brother is indeed a double threat. He is a tabula rasa, a good-boy-turned-bad-guy. There are no milestones to be met, no goals, no aspirations, no fears - nothing that determines his social status. Only a sense of absolute freedom and an air of quiet but lethal confidence instead. The young man with a wicked frame of references undergoes the biggest transformation as he begins to rediscover his real self.

Balabanov’s ‘Brat’ touched a nerve among vast audiences (from teenagers to housewives and pensioners), not because it was an action-packed thriller, but because the story was heartfelt. Many recognized themselves or their friends’ friends, relatives or neighbors in the ambivalent main character.

Danila is never seen without his Discman playing songs by popular Russian rock music – it was only the band Nautilius Pompilius in the first movie, but Danila’s music tastes became much more diverse in the sequel. A thoughtfully picked soundtrack contributed a lot to the popularity of both movies.

When ‘Brat -2’ was released in 2000, it struck a nerve once again and even managed to overshadow the success of the first movie.

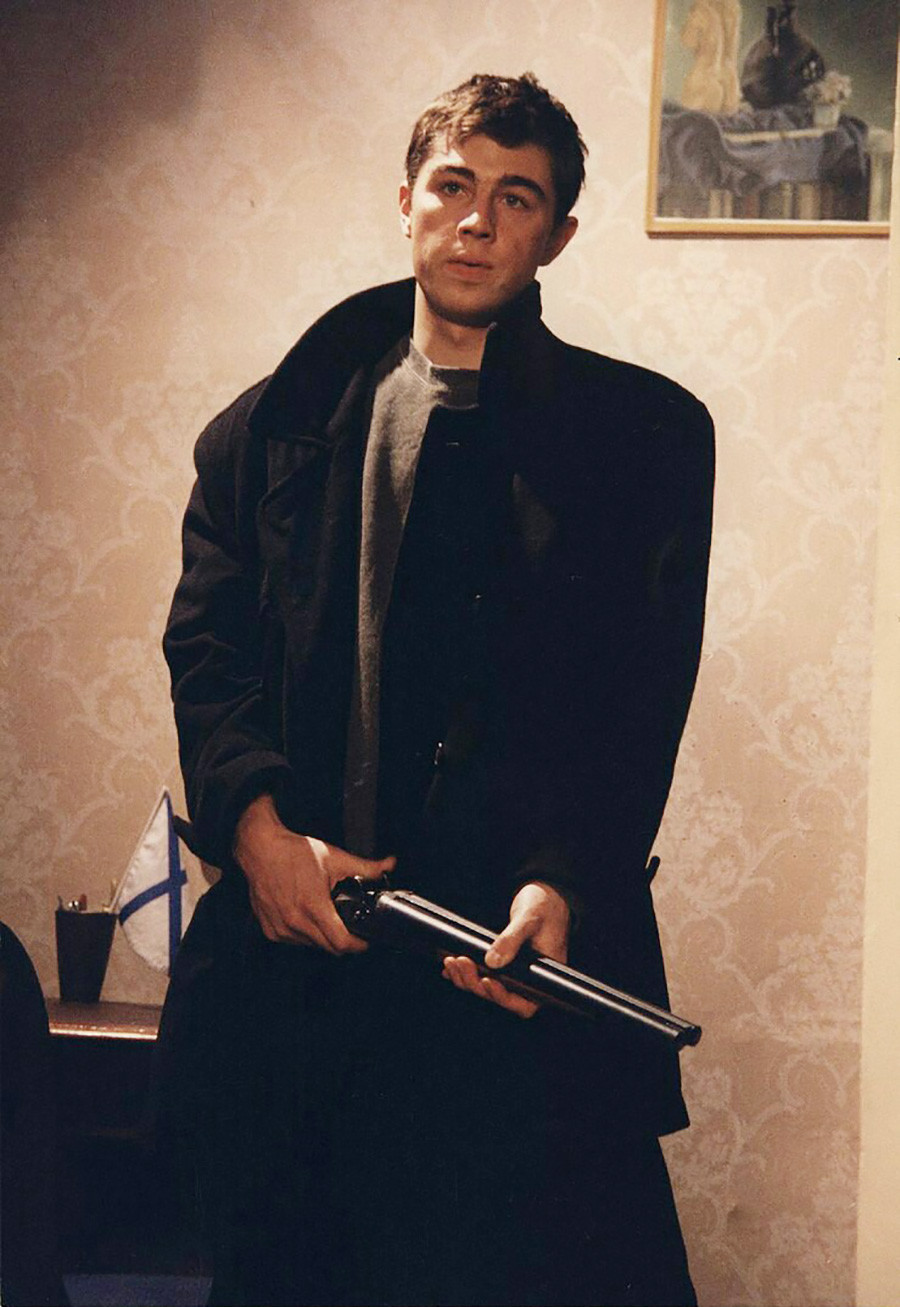

In the follow-up, Danila Bagrov makes a comeback, wearing the same heavy boots, chunky-knit beige sweater and a childish grin on his face. Danila, whose voice is blurred with eternal sadness, arrives in Moscow where he gets involved in a gang war. Things take a surprising turn when Danila and his brother Viktor travel to America to avenge his friend’s death and help his twin brother - a hockey player, unceremoniously robbed by a “bad American guy”.

In Chicago, Danila gets busy exchanging blows with African-Americans, rescuing a Russian prostitute and killing half of the city’s gangsters.

In the naïve pursuit of social truth, he wins a convincing victory over the local mafia and picks up a million dollars belonging to his gutless friend. Danila’s quixotic behavior is fueled by his biological instinct to see justice done.

In the first movie, the lead character is the underdog, an anti-hero of sorts, a “blind assassin” asking infantile questions like “What are we living for?”

In ‘Brother 2’, Danila already offers a treasure trove of ready answers, giving his enemies a piece of his mind: “Strength lies in the truth,” he famously says. “Like, you cheated somebody, made some money, but have you become stronger? No, you haven’t, because there’s no truth in it.”

With plot twists as plentiful as the number of meandering Chicago streets, the second installment appears to be like a Russian Matryoshka doll, with layers and layers of context and paint. It has it all – the pace, the scope, the story and lots of memorable catchphrases (along with some fairly racist remarks).

But here is a simple truth. The ‘Brother’ franchise has been widely regarded as Russia’s best gangster thriller to date. Scandalous, shocking, politically incorrect, the movie’s unparalleled success is probably due to its blinding authenticity.

READ MORE: What's wrong with Russians in 'Killing Eve'

Whether you like it or not, Balabanov’s magnum opus is also a vintage Polaroid snap of the entire post-Soviet decade. It’s a relic of a time that many would probably prefer to forget. The director from the Ural city of Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) was a cunning expert in human relations. He turned a blind eye to the conventional laws of the genre, adopted in mainstream cinema. For him, the language of cinema determined the type of social behavior.

READ MORE: 6 dark films by Alexey Balabanov that you need to watch

What makes a great movie? A mix of adrenalin and drive, perhaps. Both have a grain of truth, and are rarely lost in translation. But if the movie is genuinely awesome, the sound could go off and you would still have an idea of what’s going on. It works in ‘Brat’, it really does.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox