How famous writers depicted the lives of prostitutes in Imperial Russia

If it’s true that behind every successful man there’s always a strong woman, one could also say that behind each fallen woman there’s usually a weak man who pushed her.

The Gustov sisters cabaret singers

Maxim Dmitriev/Publuc DomainThe very subject of prostitution has historically been full of frustration, embarrassment and disgrace. Prostitution was legalized in Imperial Russia in 1843. If, before that, back in 1832, sex trade was officially banned (with both, the proprietors of brothels and the prostitutes punished with strict fines and the whip), just ten years later – through the efforts of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Count Lev Perovsky – Tsar Nikolai I finally recognized sex work as a somewhat lawful activity.

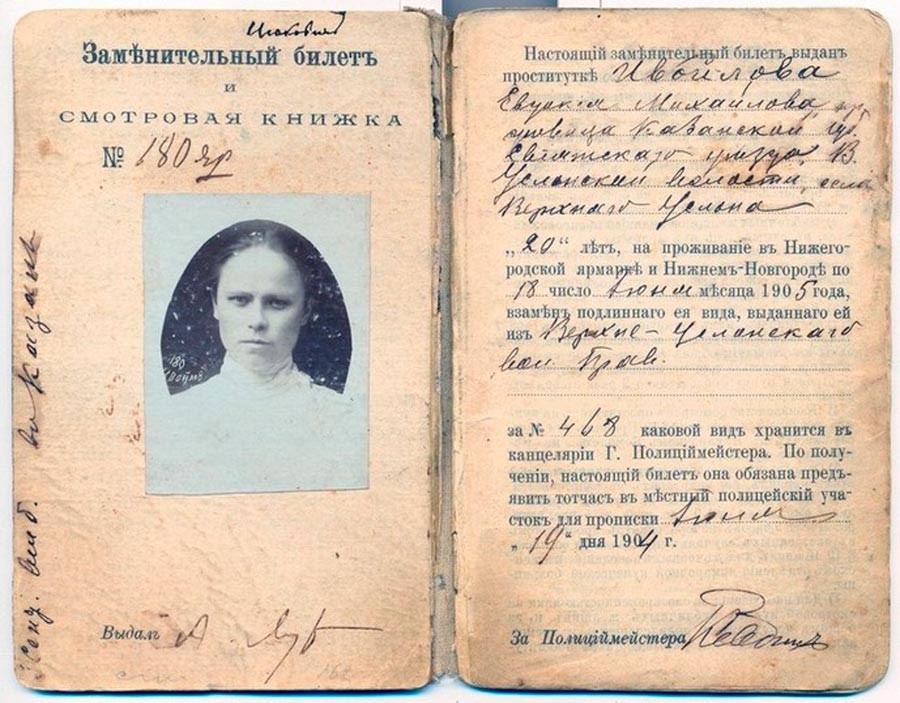

The prostitute’s internal passport withdrawn in exchange for a yellow identity card, or ticket.

Public domainAll prostitutes had to register with the police, with the woman’s internal passport withdrawn in exchange for a yellow identity card, or ticket.

The number of brothels began to multiply. In 1852, there were “only” 152 brothels in St. Petersburg, in which 884 women worked. However, in 1879, there were already 206 whorehouses with 1,528 prostitutes. Prostitutes had to undergo regular embarrassing medical examinations. The primary objective was eradication of syphilis.

However, by the beginning of the 20th century, under public pressure, the number of brothels had dramatically decreased. In 1909, only 32 of them remained in St. Petersburg. It doesn’t mean that there were fewer prostitutes, though. It’s just that more and more women began to work “on their own”.

After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, prostitution was banned by the Soviet government.

Fyodor Dostoevsky and ‘Crime and Punishment’

Sonechka Marmeladova, of Dostoevsky’s ‘Crime and Punishment’, is undoubtedly the most well known prostitute in the realm of Russian literature.

Fyodor Dostoevsky broke new ground in that he portrayed the sinful heroine as the embodiment of virtue, wisdom and innocence. Sonechka is described as a “pretty blonde with wonderful blue eyes, fixed with a stony glare of terror”.

Actress Tatiana Bedova as Soneckla Marmeladova in 'Crime and Punishment'.

Lev Kulidzhanov/Gorky Film Studio, 1969The only daughter of a titular counselor, Marmeladova is forced to sell her body to save her family from starvation. The girl, who is not yet 18, supports her alcoholic father and her sick stepmother with her three children, while suffering long-term verbal abuse from her numerous family members.

Previously, Sonya had tried to work as a seamstress, but that job brought her little or no money at all.

“...how much can, in your opinion, a poor, but honest girl earn by honest labor? If she is honest and has no special talents, she won’t even earn 15 kopecks if she works tirelessly!.. “ Sonia’s jobless and irresponsible father complains.

‘Crime and Punishment’ is set in St. Petersburg in the 1860s. To find a solvent client, Sonechka Marmeladova has to wear an outfit that clearly shows who she is and what she does on the street: “She was also in rags; her attire was pennyworth, but decorated in the street style, to the taste and rules prevailing in her own special world, with a bright and shamefully outstanding purpose. <...>”

The poor girl is the only breadwinner in the family. That’s why Rodion Raskolnikov calls her a water well, which the Marmeladov family takes advantage of without a twinge of conscience. “What a well they’ve managed to dig! And they are all using it! They do! How they got used to it! They cried and then just got used to it. A scoundrel always gets used to everything!”

By the time she meets Rodion, Sonia has fallen out of love with her own life. But it’s her tenderness that helps Raskolnikov atone for the torments of the past. One day, he falls to her knees in tears. “They have been resurrected by love, the heart of one contained endless sources of life for the other,” Dostoevsky concludes in his cult masterpiece.

READ MORE: 10 ICONIC female characters in Russian literature you need to know

Leo Tolstoy and his ‘Resurrection’

Dostoevsky wasn’t the only one to peer into the life of a fallen woman. His peer, Leo Tolstoy, took pen to paper to share his insight into prostitution in his ‘Resurrection’ written between 1889-1899, under Tsar Nicholas II.

Actress Tamara Syomina as Katyusha Maslova in 'Resurrection'.

Mikhail Schweitzer/Mosfilm, 1960Katyusha Maslova, the main character of the novel, is an orphan. The daughter of an unmarried servant and a gypsy, Katyusha grows up at the house of two noble old ladies, working as a maid. At the age of 16, she falls in love with a young aristocrat, Dmitry Nekhlyudov, who seduces her, paying 100 rubles for the intercourse, then dumps her.

Things get worse and worse. Katyusha becomes pregnant, has nowhere to go, loses her child and eventually ends up in a brothel, her eyes “black as wet currants”.

Actress Tamara Syomina as Katyusha Maslova in 'Resurrection'.

Mikhail Schweitzer/Mosfilm, 1960Paradoxically enough, the miserable young woman is not ashamed of her new status and is even proud of it, to a certain extent.

“Usually, it is thought that a thief, a murderer, a spy, a prostitute, recognizing their profession as bad, should be ashamed of it. The opposite happens. People who have been put in a certain position by fate, by their sins or by their mistakes, no matter how wrong they may be, form such a view of life, in which their position seems good and respectful to them,” Tolstoy wrote in ‘Resurrection’.

Tolstoy made waves by showing the problems of prostitution from the human point of view. He proved to be so convincing that revolutionary feminist Rosa Luxemburg wrote in her article, entitled ‘The Soul of Russian Literature’, that “the Russian artist [Tolstoy] sees in a prostitute not a ‘fallen woman’, but a person whose soul, suffering and internal struggle, ask for the artist’s compassion.”

In fact, the story of Dmitri Nekhlyudov and Katyusha Maslova appeared to be autobiographical. Tolstoy wrote in his diaries that in his youth, he “led a very bad life”, noting that two events in his life tormented him: “A relationship with a peasant woman from our village before my marriage... The second is a crime that I committed with the maid Gasha, who lived in my aunt’s house. She was innocent, I seduced her, they sent her away and she died.”

READ MORE: 7 SEDUCTIVE scenes in Russia’s greatest works of literature

Aleksandr Kuprin and ‘The Pit’

‘The Pit’ triggered an avalanche of criticism when it first saw the light of day in 1909. While working on the story, the man behind ‘The Duel’ put prostitution in the Russian Empire under a magnifying glass. The writer approached the sensitive subject with rationality and common sense.

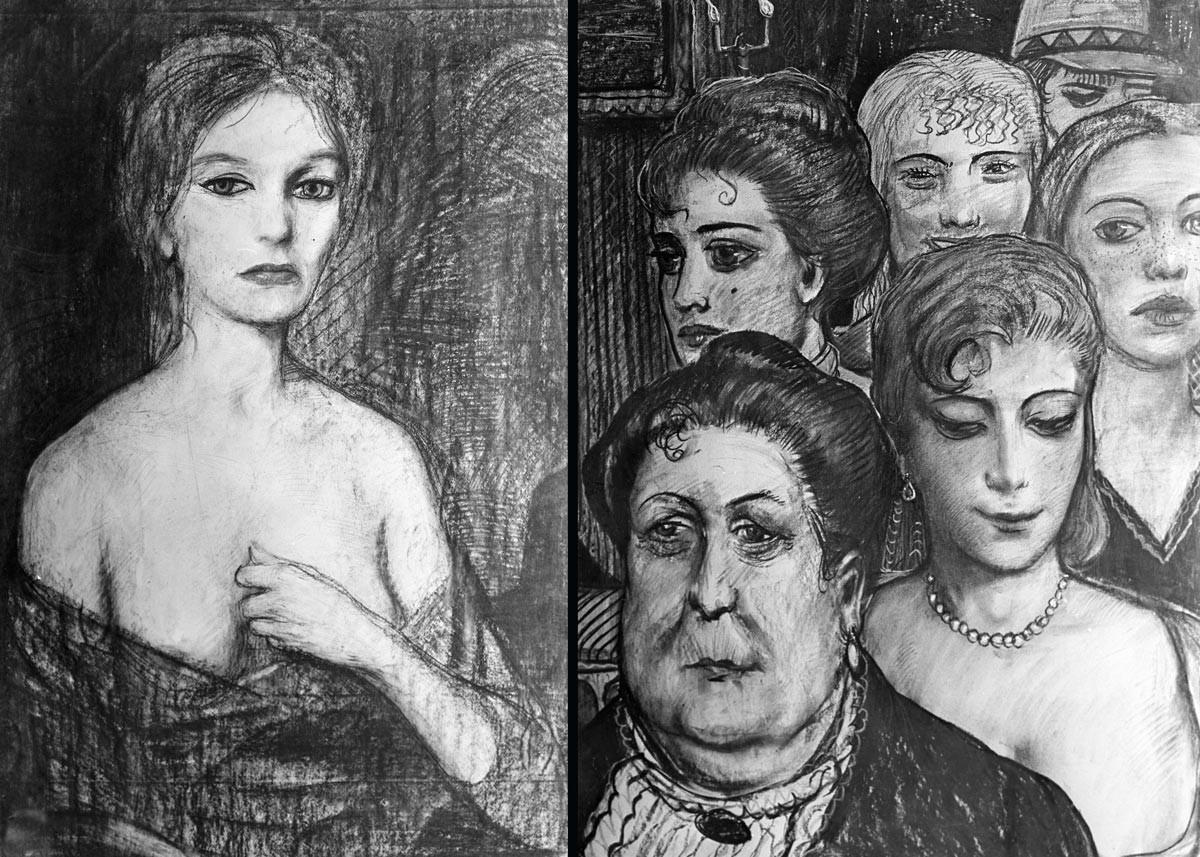

Photographic reproduction of Ilya Glazunov's illustration for 'The Pit'.

Pavel Balabanov/SputnikNonetheless, a ton of negative feedback poured out on Kurpin after the release of the first part of the novel. Many condemned his story about prostitutes at a brothel. The writer was called a “pornographer, a ruiner of youth and the author of filthy libels on men”.

While state censors called the novel “immoral and indecent”, writer of children’s literature Korney Chukovsky said ‘The Pit’ was “a slap in the face to the whole modern society”.

Kurpin described the life of Russian prostitutes with empathy and understanding. A man of integrity, courage and principle, in his youth days Kuprin had once thrown a drunken bailiff overboard, after he verbally insulted a female waitress. Kuprin never tolerated any injustice against the weaker vessel.

The main character of ‘The Pit’, a prostitute named Zhenya, becomes infected with syphilis and, in an emotional tale of revenge, decides to deliberately infect everyone else, until she meets a kind gentleman named Kolya, who treats her with unexpected respect.

“We, whom you first deprive of innocence, kick out of the house and then pay two rubles per visit, we always… hate you and never feel sorry, do you understand?!” Zhenya exclaims in the novel. Her concise confession speaks volumes about the prostitutes’ fate in Imperial Russia.

READ MORE: 10 BEST screen adaptations of Russian classics

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox