“We need millions of private owners, not a handful of millionaires,” Russian President Boris Yeltsin said in an address to the nation explaining the purpose of privatization 30 years ago.

By the end of 1991, the country was on the verge of bankruptcy. The planned economy had proved ineffectual and there was not enough money to provide support to enterprises and to pay salaries. Money was also rapidly depreciating: The rate of inflation reached a whopping 160 percent in 1991 and a mind numbing 2,508.8 percent in 1992. For a new economic model to appear, a transition to free market pricing was needed.

Anatoly Chubais, chairman of the Russian Federation State Committee for the Management of State Property.

Valentin Sobolev/TASS“Hard currency reserves were near zero. It was bad enough that the country could not afford grain, but there were no funds to pay the freight charges for delivery of the grain by ship. According to optimistic estimates, the grain reserves would last until about February or March 1992,” is how Anatoly Chubais and Yegor Gaidar described the state of the Russian economy during that period in their book ‘Crossroads in Modern Russian History’. It was they who became the chief ideological proponents of economic reforms.

The country’s leadership considered three privatization models. There was the British model, i.e. selling large, but mainly marginally profitable enterprises at below-market prices, which seemed too protracted - it could have taken up to 20 years. The model didn’t suit the new authorities because, apart from economic goals, they also pursued political interests - breaking with the Communist past as quickly as possible.

Anatoly Chubais, who was chairman of the Russian Federation State Committee for the Management of State Property at the time, said in a TV interview in 2010 that “privatization in Russia up to 1997 was never an economic process… It pursued the main goal, which was to stop Communism”.

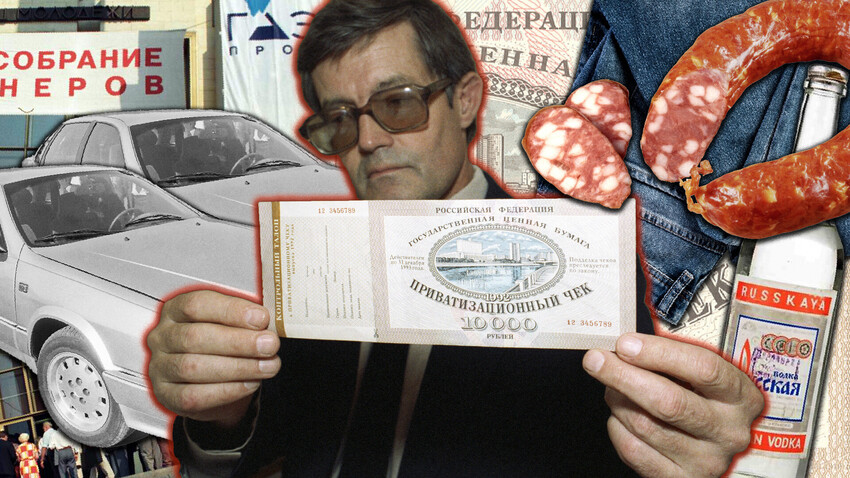

In the early 1990s, any Russian could acquire shares in major enterprises for peanuts, but only a few took advantage of this “chance of prosperity”.

Igor Zotin/TASSThe second privatization model which was considered involved opening individual investment accounts in Sberbank, but this would have been technically difficult to implement bearing in mind the low level of development of the banking system at the time and the size of the population.

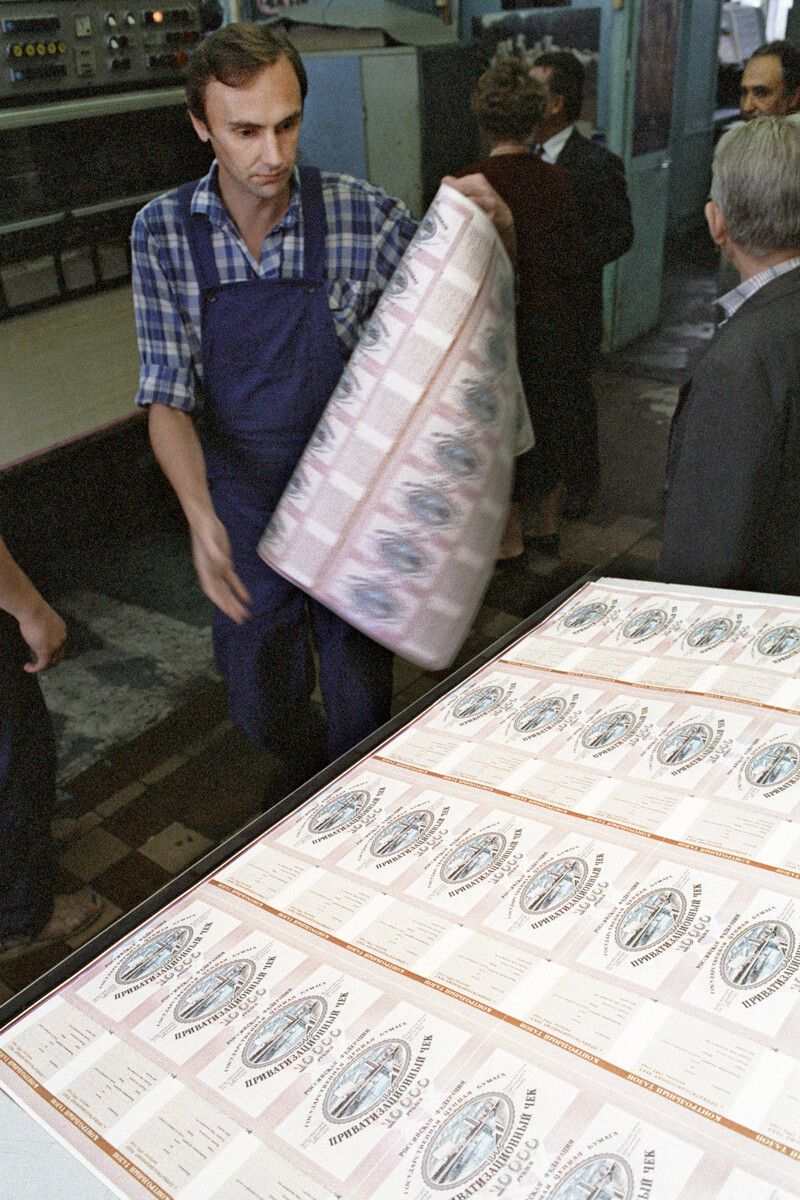

The quickest model - the Czech model - was settled on. Privatization through the distribution of vouchers that could be exchanged for shares in enterprises, sold or donated. Admittedly, in the Czech Republic, vouchers were inscribed with the holder’s name, but, in Russia, this was not the case.

Russia's first President Boris Yeltsin receives a privatization check, 1993.

Dmitri Donskoy/SputnikOn August 14, 1992, Boris Yeltsin signed a decree on the distribution of vouchers to the public. In theory, any Russian could become part-owner of a large enterprise. For 25 rubles (a paltry sum in those days), every Russian citizen could acquire a privatization check (voucher) with a face value of 10,000 rubles.

At the time, the state property that was subject to privatization was valued at 1.4 trillion rubles. The distribution of 140 million vouchers began. Every citizen of Russia - “from infant to the most senior citizen” - was entitled to a voucher.

Large industrial enterprises, agricultural enterprises (collective and state farms), land and the housing stock were part of the privatization program, transforming them from state assets into joint-stock companies. Privatization in certain sectors was prohibited (mineral resources, timber, offshore industries, pipelines, public roadways). With time, the list of enterprises and industries was extended.

In practice, it was difficult to establish the real value of the property. Figures taken from planning estimates were used as the basis of the calculations, but, for objectivity, the assets should have been floated on the stock market.

“Given high inflation and macroeconomic instability, the privatized assets ended up undervalued and the proceeds from privatization received by the state budget were insignificant and this, in turn, reduced the legitimacy of privatization,” believes economist Sergei Guriev.

An auction of shares in the Bolshevik confectionery factory, 1992.

Alexei Boytsov/SputnikEveryone who acquired a voucher was given a leaflet that said: “A privatization voucher is a chance of prosperity given to everyone. Remember: Anyone who buys vouchers is increasing their chances, while those who sell are missing out on opportunities!”

The vouchers could be used to acquire shares in any Russian enterprise that was being privatized. The price of the shares was determined at auction. Aside from that, workers could obtain shares in their own enterprise at a discount. A total of 9,342 auctions were conducted between December 1992 and February 1994, at which 52,000,000 vouchers were used.

Those Russians who bought shares in large companies that exported abroad proved more successful than others. Enterprises that served the domestic market had a much tougher time. The public lacked the money to buy their products. Many enterprises went under.

Gazprom shares proved to be among the most lucrative investments, but the situation surrounding them was not straightforward. The shares were priced differently in different regions. In Perm Region, 6,000 Gazprom shares could be acquired for one voucher, while, in Moscow, it was only 30 shares and, in the neighboring Moscow Region, the number was 300. (At the current exchange rate and price per share, 6,000 Gazprom shares are worth over $30,000).

And while some were exchanging their vouchers for shares in the energy giant, others were selling them to middlemen or exchanging them for food, vodka or household appliances.

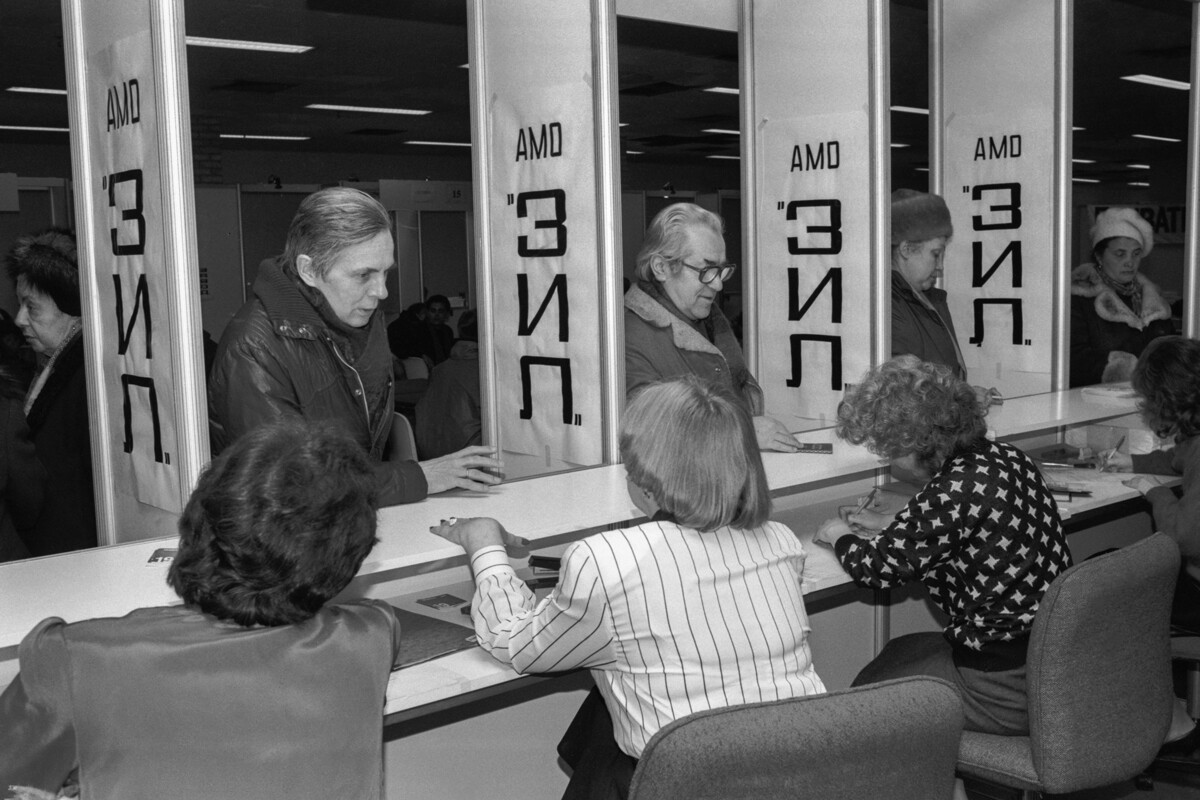

Auction at the ZIL automobile plant, 1993.

Robert Netelev/TASSAt the start of privatization, the heads of plants and factories - the so-called “red directors”, who had been put in positions of authority in the Soviet period - had the upper hand. They encouraged their workers to sell their shares and were able to withhold their wages to force them to comply. As a result, the “red directors” became sole owners of large enterprises. But, since they lacked the skills to work in market conditions, many lost their positions. Enterprises passed into the hands of financial groups, not without support from criminal circles.

In addition, voucher investment funds started to spring up all over the country into which members of the public could deposit their vouchers and receive dividends. But many people did not receive any. Only 136 companies out of 646 funds paid out dividends. The others were ignominiously dissolved.

Consequently, 60-70 percent of retail, public catering and consumer services enterprises had been privatized by the end of 1994. The fate of the vouchers was as follows: 50 percent of voucher holders invested them in the enterprises where they worked, around 25 percent of vouchers went into voucher funds and 25 percent were sold.

The biggest blow to the legitimacy of privatization was dealt by the loans-for-shares auctions held from 1995 onwards. The government obtained loans against state shareholdings in large companies (Yukos, Norilsk Nickel, etc), but never paid them off. The mortgaged shareholdings passed to the creditors, who, thus, ended up owning shares in the companies at below-market prices.

“The sole social stratum prepared to support Yeltsin at that time was big business,” wrote Yevgeny Yasin, Russian Federation minister for the economy (1994-97). For its services, big business wanted to get its hands on coveted chunks of state property. Aside from that, they wanted to exert a direct influence on politics. That was the origin of the oligarchs.” (‘Democrats to the exit!’, Moskovskie Novosti newspaper, 2003, № 44, November 18).

According to research by the compilers of the Forbes List in 2012, two-thirds of Russian dollar billionaires had secured the main part of their fortunes during privatization.

Bolshevik confectionery factory, 1992.

Alexei Boytsov/SputnikIn the early years of privatization, public attitudes to it were neutral. Pollster Tatyana Zaslavskaya wrote in 1995: “As far as <…> the behavior of mass social groups is concerned, the implementation of privatization has, so far, not had any significant impact on them… Only 7 percent of workers see a direct dependency between earnings and personal effort, with the remainder believing that the main paths to success are the use of family and social connections, speculative trading, fraudulent practices and so on.” (‘Russia in Search of the Future’, Sociologicheskie Issledovaniya journal, 1996, № 3)

Attitudes towards privatization were to change with the passage of the years. A poll conducted by the VCIOM Center in 2017 on the 25th anniversary of privatization found that 73 percent of the population had a negative view of its results.

Gazprom, the first annual shareholders meeting, 1995.

gazprom.ruDespite the criticism of privatization as illegitimate, it fundamentally altered the country’s economy. Professor Sergei Orlov, Doctor of Economic Sciences, believes that privatization marked a step in the direction of shaping a proper economic way of thinking and understanding of a free and competitive market in the public mind. In his view, it laid the foundation for the establishment of today’s retail and services sector, agroindustrial complex and construction industry, which have been developing dynamically since the late 1990s.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox