How the Bolsheviks revolutionized the Russian language

Children demonstrating in Moscow, June 1, 1923

Getty ImagesThe idea of reforming the Russian language was in the air even before the Revolution, but the Russian Academy of Sciences took a long time to set the reform in motion and was in no hurry to introduce it across the country. After 1917, the new Bolshevik government acted much more decisively: its intention was to ditch everything “old” - the tsarist regime, religion, the economy, and the language.

In 1918, a decree on new spelling rules was issued and all printed publications were obliged to follow them. The pre-revolutionary spelling was virtually outlawed.

Why reform was needed

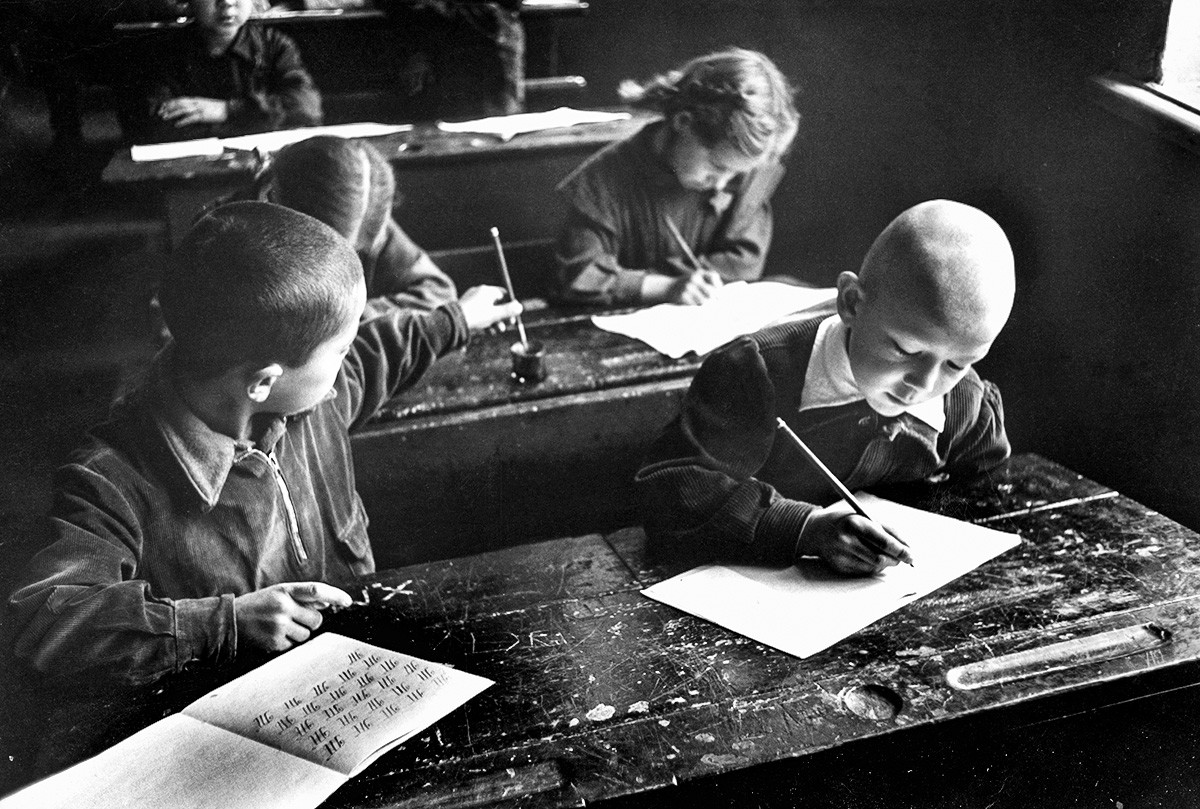

Soviet schoolchildren on the spelling lesson

Getty ImagesThe Imperial era spelling was rather difficult, and the Bolsheviks needed a language reform in order to, among other things, make learning easier. After all, one of their main tasks was the elimination of illiteracy. Several years before the Bolshevik Revolution, according to various estimates, only about 40 percent of the Russian population could read and write. But the new ruling class proclaimed by Vladimir Lenin - the workers and peasants – was expected to be active in all spheres of life. So, the young Soviet government ordered the entire population, aged eight to 50, to learn to read and write.

A census conducted in 1926 showed that in just a few years the share of literate people in rural areas rose to about 50 percent.

The alphabet lost several letters

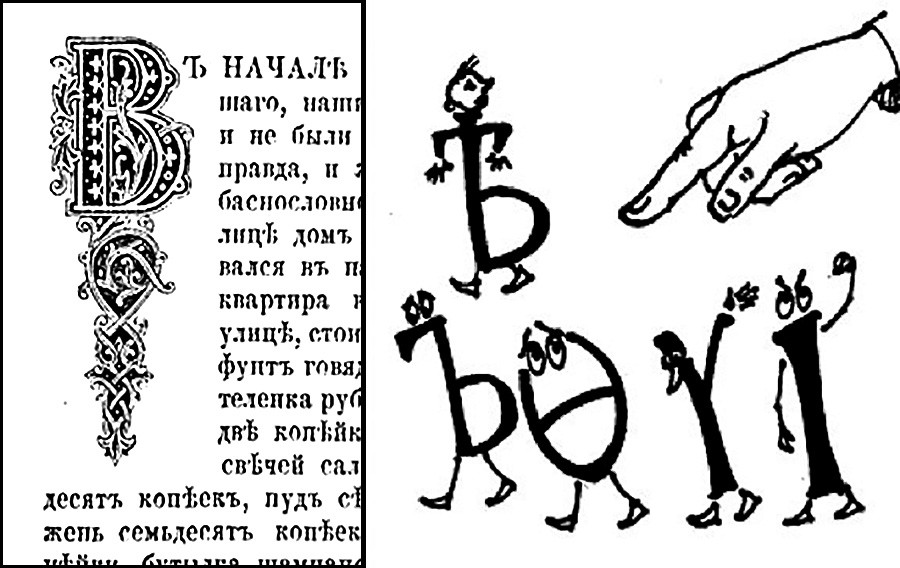

Letters that left the Russian alphabet

Public DomainBefore the Revolution, the Russian alphabet consisted of 35 letters. There was no single set of spelling rules - only a civil script approved by Peter the Great, who sought to limit the power of the Orthodox Church. so he came up with a simplified script for government decrees, secular documents and the first newspapers.

The Bolsheviks expunged a couple of letters and replaced several others with simpler equivalents that already existed in the alphabet (and to combine letters that sounded equally into one). Thus, soon after the Revolution, the Russian alphabet had 32 letters. Later the letter "ё" was approved as a separate character, so the number of letters rose to 33. And has remained the same since.

Vladimir Lenin (left) and Anatoly Lunacharsky (right) who was in charge of the spelling reform

SputnikThe decree on new spelling ruled:

1. To eliminate the letter "ѣ" (called yat'), replacing it with "е" (колѣно - колено, вѣра - вера, въ избѣ - в избе).

2. To eliminate the letter "ѳ" (called phita), replacing it with "ф" (Фома, Афанасий, фимиам, кафедра).

3. To stop using the letter "ъ" (called er) at the end of words and parts of compound words (въ избѣ - в избе, хлѣбъ - хлеб, контръ-адмиралъ - контр-адмирал). This rule was quite tricky since one had to memorize the words that required an "ъ" at the end. One advantage was that it helped to save up to 4 percent of printed text. Linguist Lev Uspensky once calculated that "ъ" took up 8.5 million pages every year.

However, the letter "ъ" was retained in the middle of words as a separating ("hard") sign (съемка, разъяснить, адъютант). This is how it is used still – you can learn more about how this letter works by clicking here.

4. To eliminate the letter "і" (known as decadic "и"), replacing it with "и" (ученіе - учение, Россія - Россия, Іоаннъ - Иоанн). This rule later caused some difficulty because in cursive handwriting, the letter “и” blends with the letters “ш” or “м”. Try this test to figure out what is written there.

5. To advise use of the letter «ё» (пёс, вёл, всё) though this was not obligatory.

Interestingly, the decree made no mention of another letter in the old alphabet – "ѵ" (called izhitsa). Admittedly, it was hardly ever used: while common in religious texts, it gradually transformed into its twin, the letter "и".

What else was changed

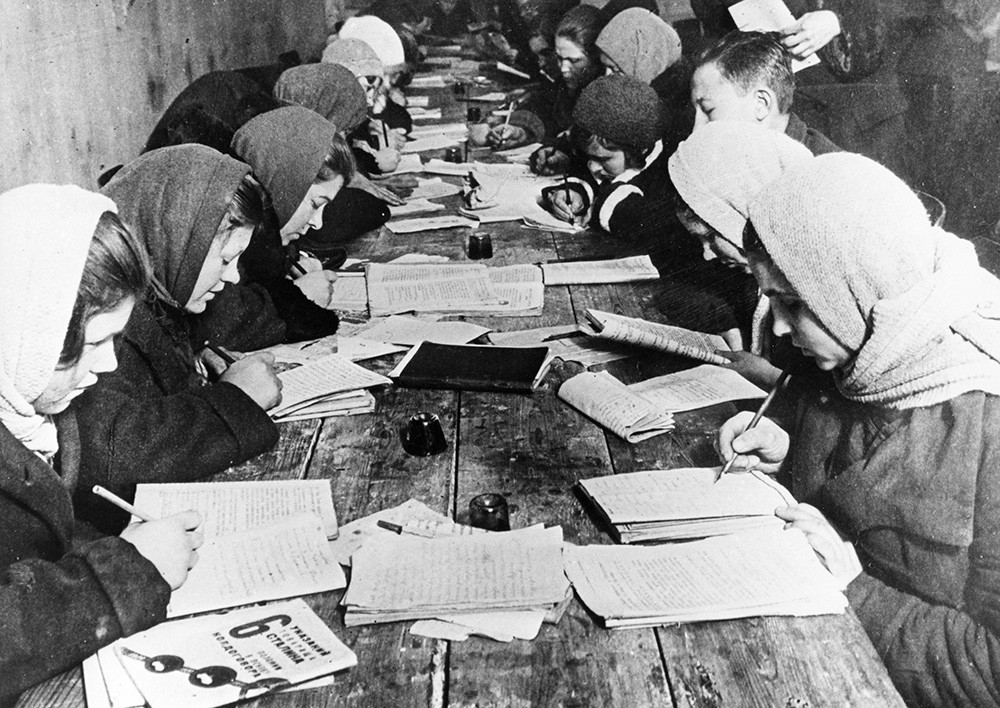

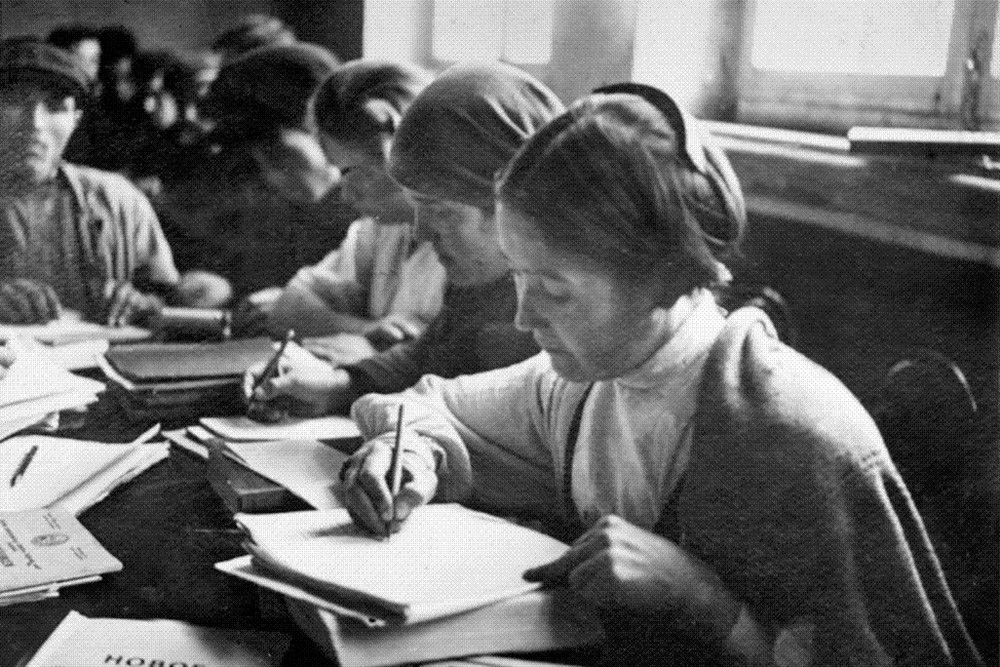

A literacy class for a factory workers in Moscow, 1932

Getty ImagesIn addition to the alphabet, several spelling rules were also changed.

For example, prefixes ending in "з" (из, воз, раз, роз, низ, без, чрез, через) now had to be spelt differently, depending on which letter followed them: before vowels and voiced consonants they ended with a "з"; but before voiceless consonants, "з" was replaced with "с" (разбить, разораться, but расступиться)

At the same time, the prefix "c" remained unchanged regardless which letter followed it.

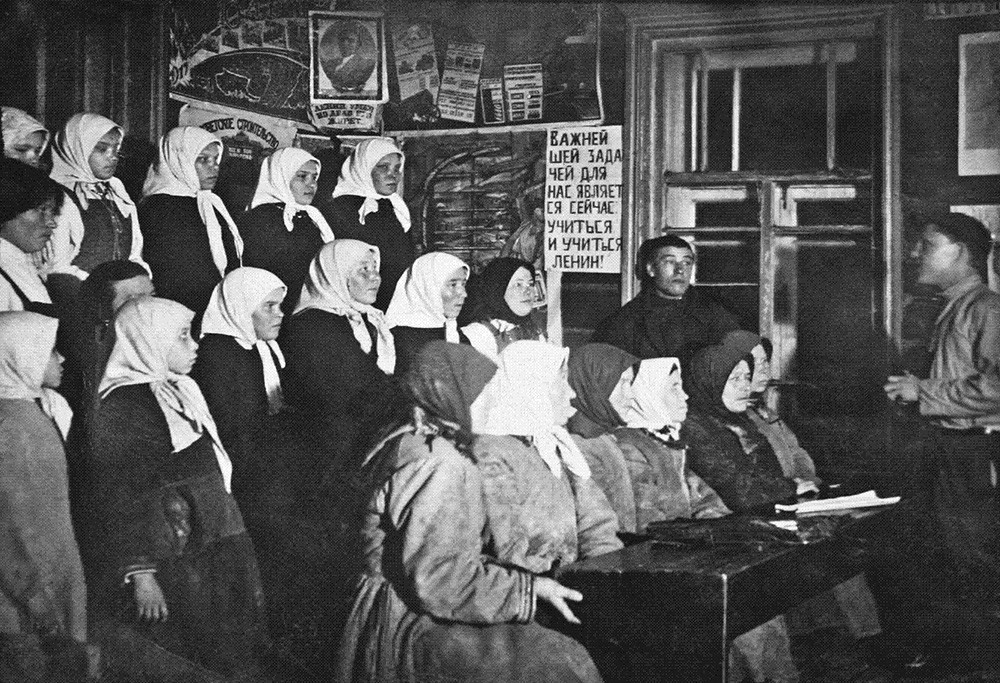

Literacy classes in a village, 1930s

Public DomainComplex rules for endings in some case forms were also changed:

- In the genitive case of adjectives, participles and pronouns, “ого”, “его” were used instead of “аго”, “яго” (добраго - доброго, ранняго - раннего).

- In the nominative and accusative cases, in feminine and neuter adjectives, participles and pronouns, the endings “ыя”, “ія” were replaced with “ые”, “ие” (добрыя - добрые, синія - синие).

- The plural pronoun “они” used to have a feminine (“онѣ”) and a masculine (“они”) form. Now only one form, “они”, remained. The same applied to the numeral “один” in the feminine (Одне - одни, однехъ - одних, etc.).

- The possessive pronoun, “ея” in the genitive singular, turned into "ее" (or "её").

How the reform was received in society

A spelling class in Cheboksary, 1930s

Public DomainWhite émigrés who left the country after the Revolution refused to accept the new spelling, and accused the Bolsheviks of mutilating the Russian language. Up until the 1940s and 1950s, Russian émigré publications were printed using the old spelling. Later, they were taught the new rules and grew accustomed to them.

Difficulties were also experienced by people who had already learned to read and write. In private correspondence many continued to use the old style of spelling, while others had to quickly relearn the new rules. Above all, teachers had to get used to the new spelling.

One of the biggest challenges came with the need to "translate" into the new style all the works of 18th and 19th century Russian classical literature. For example, some rhymes in poetry were affected by the new rules governing word endings. That said, this colossal effort also brought some advantages: the works of many great writers, which had been scattered across various literary magazines and collections, were finally gathered together, “translated” and published in a single collection.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox