What was wrong with life in the USSR?

We won't enter here into lengthy discussions about the pros and cons of the Soviet Union. Instead, we shall give the floor to real people who lived there, and ask them the following question: "Putting aside all the good things, what did you not like about life in the USSR? And how do you remember it?"

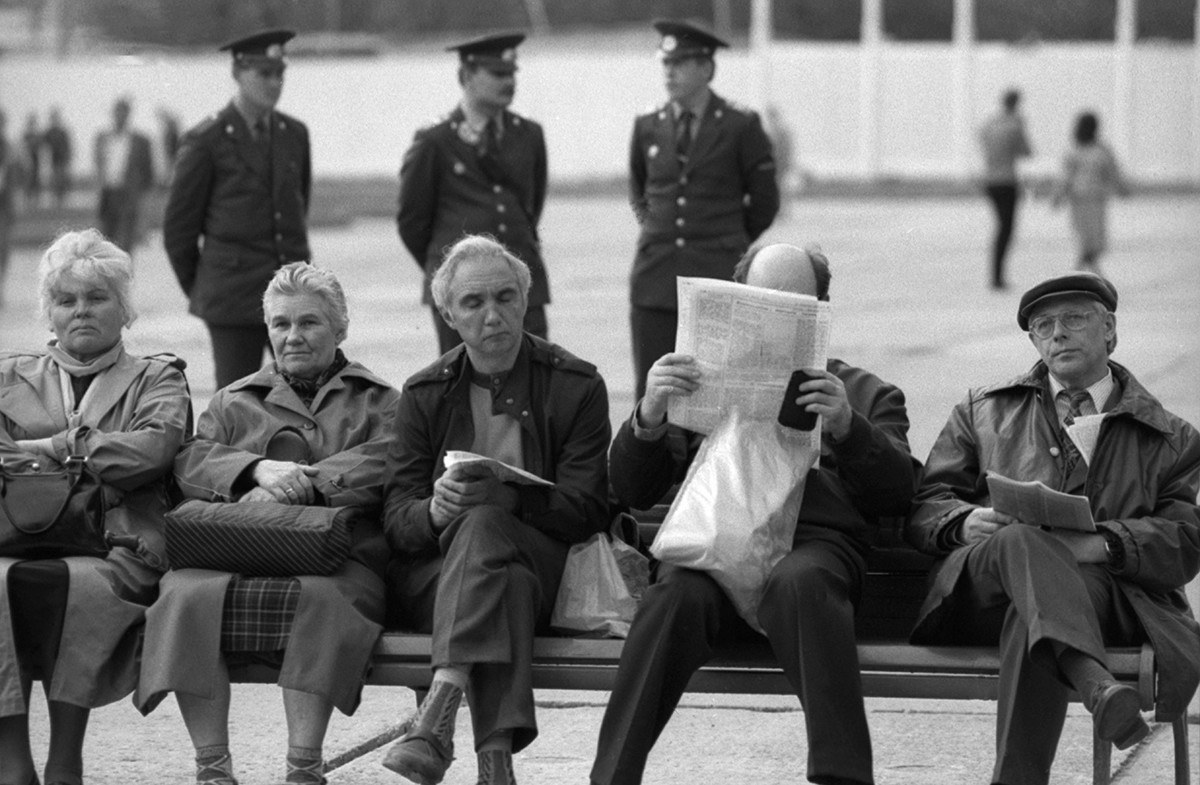

1. Total state control over all spheres of life

Moscow, 1989

Fred Grinberg/Sputnik

Vera Ivanovna, 89, former head of the planning department of an aerospace industry enterprise

I lived most of my life in the Soviet Union and remember that country well. The enterprise I worked at manufactured aviation engines and designed aircraft – even the iconic Buran orbital shuttle was built at our plant.

We were paid well, but what could we spend our money on? There was little we could buy freely over the counter. To buy a car, you had to put your name down years in advance, or pay three times the price to middlemen; land was allocated and could not be bought; and at the time, no one had heard of cooperative flats [owned by those who lived in them]. In other words, we constantly faced a situation whereby we could not buy what we wanted with the money that we earned.

I really enjoyed travelling and always wanted to see foreign countries. Such trips had to be approved by the [Communist] Party and permission was needed from the state security agencies for the issue of a foreign travel passport. And even then, people could only visit socialist countries. I was never allowed to go on a tourist trip abroad and I never had a foreign travel passport. It is a great pity that, when I was young, and my health allowed me to travel, the Soviet Union didn't allow me to do so.

The USSR always had one great advantage. We could feel the support of the state. Having survived the war, we were not afraid of starvation, and there was a certain confidence in the future. But we were locked inside a country that essentially planned our life for us. When you realize this, you begin to feel uncomfortable. But it may also be true that it was the only way of surviving the postwar years – I can’t say for certain.

2. The Communist Party and its power over citizens

Raisa Semenovna, 89, former employee of the USSR Ministry of the Chemical Industry

At the Ministry of the Chemical Industry I was in charge of the oversight of the state technical standards (known as GOSTs) for chemicals. These compounds are needed by different industries – for the production of paints, medicines, chemical fertilizer etc.

Our state standards were set at foreign levels – the state made sure that Soviet products were no worse than Western ones. And to work with foreign chemists, Soviet specialists went abroad, to socialist bloc countries like Poland, Hungary or Bulgaria… But I was never sent abroad for work, because I wasn't a member of the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union]!

I had a husband and a child, I had to look after my family and do the shopping, cooking and cleaning. But if I had joined the CPSU, I would have had to attend meetings during work time, and make speeches, as well as take part in [pro-Communist] rallies and other events. I didn't want to do all that, and, therefore, didn't stand a chance of being promoted.

Things were such that if a person was not a party member, he or she would never be appointed to, say, head of department, no matter how deserving or talented they may have been. Only party members were appointed to senior positions and, to be honest, they were not always notable for their talent, and their way of life was far from "socialist".

3. Information deficit

An applicant at the entrance exams to the Moscow textile institute after A. N. Kosygin, 1988

Boris Kavashkin/TASSTatiana Aleksandrovna, 62, fashion designer

The main problem for me and my designer friends and colleagues was the inaccessibility of information: it was impossible to learn about world trends and gain know-how in the field of design. We received all this information post factum. We were guided entirely by our own intuition: "Clearly, red was in fashion this year, so what color will it be next year?"

Nuggets of information could be found in foreign fashion and design magazines, but it was very difficult to get hold of them. You could get into closed departmental libraries – like those of the All-Union Fashion House or the All-Union Institute of Product Assortment and Culture of Dress under the Ministry of Light Industry – but only if you had the right papers. Either you worked in the field and brought a referral from your place of work, or you could get in using a student pass when you were still at university. Also, these libraries sold information to other organizations – they would photograph and review these magazines, send out cutouts and patterns by mail, etc.

And we, ordinary students, would form groups and visit the apartments of people who had managed to get hold of a copy of such a magazine for at least one night, and we would end up sitting almost on top of one another to read it, copying out articles and making drawings… Incidentally, it was also incredibly difficult to get hold of things like good quality paper, tools, paints and pencils.

4. Shortages of goods and culture

Street sellers near a children's department store

Mamontov Sergey, Nemenov Alexander/TASSOleg, 46, Russia Beyond editor

My entire childhood effectively ended up being spent in the USSR. In 1991 I finished 11th grade. This probably explains my fairly narrow range of needs and interests, which in those days could not be satisfied for obvious reasons. Most of them were purely consumerist – to do with food and clothing, which were particularly subject to shortages. The list of items might sound ridiculous today, but the shortage of basic cheeses, sausages, meat and ordinary chewing gum, and brightly-colored clothes and footwear for children, was a sensitive issue. It was particularly so given that comparisons were already available then – all these things could be acquired in Moscow (I lived in provincial Taganrog at the time) or from spivs on the black market, or be seen worn by, or in the possession of, my more "successful" peers, whose parents had the opportunity to make rare trips to countries of the socialist camp.

But for me personally, the much talked-about Iron Curtain and wholesale shortages entailed an absolutely hopeless problem – the impossibility of cultural exchange. In the USSR, the history of world literature and art ended with, respectively, the anti-war prose of Erich Maria Remarque and French modernism of the early 20th century. It was a big problem that even these crumbs of knowledge could only be acquired in specialist libraries, which themselves did not smell of modernity. And this painful information vacuum pursued us right up until the time of perestroika, which became a new Renaissance.

Sellers in the street near the "Detskiy Mir" central department store in Moscow

Khristoforov Valeriy/TASSGeorgy Gennadievitch, 64, former manager

There were people who constantly visited foreign countries for work reasons – sailors, pilots, railwaymen and athletes – and they brought back goods which were sold and resold by blackmarketeers, who existed in all major cities in the USSR. In cities like Riga, Leningrad and Odessa, it was such a thriving trade that blackmarketeers from other towns travelled here specially to acquire such goods – records, magazines, illustrated art books, tape recorders, watches, cine and still cameras, and so on – in order to resell them in their hometowns. Thus, in prohibiting the free import of foreign goods, the Soviet authorities were encouraging the emergence and continuing existence of illegal trade – and profited off it through bribery.

5. Inefficiency of the planned economy

AZLK automobile plant, Moscow, 1974

Valentin Khukhlaev/TASSEvgeny Semyonovitch, 81, former worker at the AZLK automobile plant

Our factory operated according to production plans handed down from above, from the ministries. And the plan was inadequate for ensuring full supplies of parts for the manufacturing process – because it was drawn up by bureaucrats who needed fine-sounding and convenient figures, by people who did not take account of the specific peculiarities of actual production.

Suppose the plant’s various workshops were making 100 percent of the parts dictated by the plan. We simply couldn't have made more because, under the plan, we only had semi-finished parts and materials for 100 percent of the components. So what about the parts that proved to be faulty? A certain portion of sub-standard components were branded as ‘rejected’ and sent to a designated storage area. Let's say 80 percent of the manufactured components were sent on for the assembly of vehicles – but, when there weren't enough to go around, the missing components were brought back from rejected storage. According to the "whatever's left over" principle – and so that the components did not go to waste, the contents of the rejected store were sent on to shops selling spare parts. And that is how substandard vehicles ended up coming off the production line, and unsellable spare parts turned up in shops.

People standing in line for vodka, Kaliningrad, USSR, 1986

S. A. Bulatov family archive / "Kaskad+" media holdingThe planned economy had a pernicious effect on the quality of workers in manufacturing. At the famous 1970 London to Mexico motor rally, the AZLK team with its ‘Moskvitch’ cars (Москвич, ‘The Muscovite’) came third in the team ranking. At that time, the plant had been producing 60,000 vehicles a year. Inspired by this success, the Soviet leadership decided to increase car production immediately the following year. But where were the additional workers for this extra output to come from? As a result, in order – once again – to satisfy the requirements of the plan, "temporarily allocated workers"' began to be recruited instead of specialists – untrained people from the sticks sent to Moscow under a labor quota system. These "temporarily allocated workers" had, if you’ll excuse my bluntness, been herding cows only yesterday, and now they were being placed in front of a lathe. The quality of assembly fell sharply, but now 100,000 cars were being turned out per annum instead of 60,000. The quality of the cars, however, was now of course very far removed from earlier series.

6. Decision-making without regard for people’s needs

USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev, speaking on the "Visiting Dmitry Gordon" talk show, 2010

Three general secretaries died one after the other [in the 1980s – Leonid Brezhnev (1906-1982), Yuri Andropov (1914-1984), Konstantin Chernenko (1911-1985)]. Society was simply unhappy with the old leadership, the ailing leadership – many of them were positively ill when they came [to power]. When I came in [as general secretary of the CPSU Central Committee in 1985], the supply of leaders in good health was exhausted. I think the country could not have been left in that condition. Everything important in our country was taking place in the privacy of people's kitchens – the important discussions and conversations. People were unhappy that a country with enormous potential was incapable of dealing with perfectly simple things. Should tooth powder or soap really have been a problem? Or toilet paper? Or – a commission under Ivan Vasilyevich Kapitonov was set up to sort out the problem of women's stockings! Can you imagine?

In other words, the system really wasn’t working. And it wasn't working because private individuals were excluded from the process of formulating and taking decisions. I'm not saying that everyone should have gone and sat on the Central Committee, no – what I'm getting at is that people needed to have the opportunity to express their view, they needed ‘glasnost’. And what glasnost could there be in a system in which, as soon as someone told a hard-hitting joke, they were hauled off for re-education somewhere and for a long time. People did not want to live like that. It was an educated country, after all. And so the phrase "we can't continue to live like this" was coined. The country was suffocating from unfreedom.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox