What actually caused the Russo-French War of 1812?

In this article, we do not go into the military details of Napoleon’s 1812 campaign against Russia – you can read them here. Rather, this article is aimed at explaining the political and economical reasons behind the biggest military conflict of the 19th century.

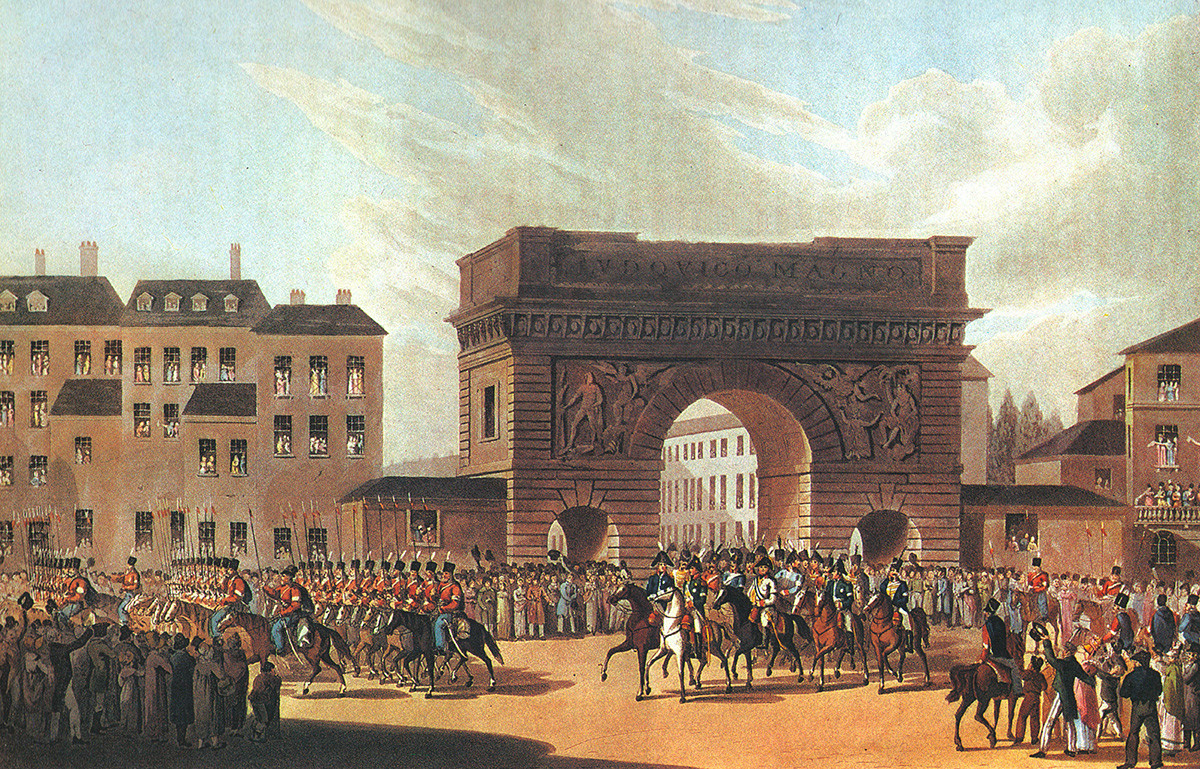

Napoleon’s 1812 ‘Russian Campaign’

Entry of Napoleon I into Berlin, 27th October 1806, by Charles Meynier

Palace of VersaillesThe main reason why the 1812 war between Napoleon’s France and Russia began was sanctions – the so-called Napoleon’s ‘Continental System’. But what was it?

In 1792-1793, the Republic of France was involved in the French Revolutionary Wars – France fought against Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, Russia and several other monarchies. The “old” monarchies of Europe detested the republican system of government installed in France. Meanwhile, Napoleon Bonaparte emerged in France, a young genius war commander, who, by 1799, had become de facto leader of France.

By the beginning of the 1800s, France had conquered territories on the Italian Peninsula, the Netherlands and the Rhineland. Great Britain remained France’s only opponent in Europe. After the Battle of Trafalgar of 1805, it became obvious that the French navy was useless against the British fleet, so Napoleon began strengthening the Continental System – a large-scale embargo against British trade on the European continent.

READ MORE: How did Napoleon come to be respected in Russia?

Napoleon wanted to destroy Britain’s ability to trade, to drain it financially. The Berlin Decree of 1806 proclaimed that “the British Isles are declared to be in a state of blockade” and forbade all correspondence or commerce with Great Britain. However, European countries constantly breached the blockade, which caused attacks on them by Napoleonic France. The Russian Empire, Great Britain’s main European economic partner at the time, was also France’s main enemy and the main obstacle in successfully implementing the Continental System.

Russia and the Continental System

Meeting between Napoleon Bonaparte and Czar Alexander I Romanov at Tilsit, June 25, 1807.

DEA/M. SEEMULLER/Getty ImagesIn the Battle of Friedland (1807), Napoleon defeated, if not crushed, the Russian army. After that, Alexander I of Russia agreed to sign the Treaty of Tilsit, which had Russia and Prussia ally with France against Great Britain and Sweden.

READ MORE: Why did Napoleon invade Russia?

The Treaty of Tilsit enraged the Russian public – making peace with a republican whose army put thousands of Russian soldiers to death! However, by 1810, Russia resumed trade with England through other countries, while French goods were taxed heavily. Meanwhile, Napoleon tried to strengthen his ties with Alexander I by offering his hand to Alexander’s sisters, but was refused twice.

By 1811, Napoleon was openly speaking about his hostile attitude towards Russia. He said to Dominique Dufour de Pradt, the French ambassador in Warsaw: “In five years, I shall be the master of the world, Russia alone remains; but I shall crush her... I shall then also be the master of the seas and all commerce must, of course, pass through my hands.” It had been obvious the war was near.

What was this war for Russia

"Mikhail Kutuzov as the head of the St. Petersburg militia," by S. Gerasimov

Ministry of Defense of the Russian FederationSkipping the innumerable details of Russian and French warfare at the time, we’ll stick to the core events of the war. Roughly by June 24, 1812, when the Great Army invaded the Russian Empire by crossing the Neman River, Napoleon had about 588,000 troops against Russian 480,000, but the Russians were fighting at home and with the aid of Russian partisans, who terrified the French throughout their “stay” in Russia.

As researcher Mikhail Belizhev notes, “The scale of the war itself was unique. For the first time since the 17th century, war was waged on the territory of the Russian Empire, which was a real shock for contemporaries. Moscow, the heart of the empire, was given to the French and largely destroyed – at that time, it was interpreted as a national catastrophe. The country suffered enormous losses: up to a million residents of Russia perished in 1812-1814; material damage was estimated at several billion rubles.”

"The arrival of Mikhail Kutuzov in Tsarevo-Zaymishche" ("Kutuzov takes the command over the Russian Imperial Army"), by Sergey Gerasimov

Panorama Museum "Battle of Borodino"The Great Army decisively entered Russia and, enduring constant resistance from the Russian army, moved towards Smolensk, the fortress considered the “key to Moscow” and took it in August 1812. However, the onslaught wasn’t easy, as both the Russian army and civilian population implemented a scorched-earth policy: when retreating, the Russian soldiers destroyed food storages, ammo supplies and any assets that could be used by the enemy. Who implemented this policy?

The Scottish man behind the Russian victory

Mikhail B. Barclay de Tolly (1761-1818). Russian Fieldmarshal and Minister of War. Portrait by George Dawe (1781-1829), 1829. The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

PHAS/Universal Images/Getty ImagesMichael Andreas Barclay de Tolly (1761-1818) was a Baltic German officer of Scottish origin in the Russian service. A descendant of the Scottish Clan Barclay, he grew up in St. Petersburg and entered the military service in 1776. He would later become field marshal of the Russian Empire.

Barclay was War Minister in 1810-1812. He effectively prepared the Russian army for the decisive fight with Napoleon, ordering and personally creating a great lot of tactical and strategic tutorials and manuals for the soldiers and officers. When the war began, Barclay and General Pyotr Bagration were both functioning as commanders-in-chief of the Russian army.

"The Military Council in Fili" (1880) by Sergey Kivshenko

Tretyakov GalleryHowever, it was Barclay who initially devised the masterplan for the Russian army during this war: using a scorched-earth policy, retreat back into Central Russia to drain the resources of the French army. The French supply routes, Barclay rightfully reckoned, would become too long to supply the army from Europe and the Russian partisans and the army would do the rest to crush the enemy.

At the Council at Fili, which happened shortly after the Battle of Borodino, Barclay firmly voted for leaving Moscow to Napoleon, a wise strategic move that eventually captured the French Emperor in cold, brazen and burning Moscow, devoid of supplies. Trusting the command of the army to Mikhail Kutuzov, Barclay nevertheless stayed in command of one of the armies and fought later in Russia’s European campaign of 1812-1814.

"The entry of Russian troops into Paris. March 31, 1814": an unknown artist from the original by I. F. Yugel based on a drawing by U.L. Wolf, 1815.

Pushkin MuseumRussian historians of the 1812 campaign are unanimous in the opinion that Barclay’s initial strategy wasn’t changed by Mikhail Kutuzov as he took command of the army. After the victory over Napoleon, Barclay was showered with awards and recognitions. He was elevated to princely dignity by Emperor Alexander I and widely considered to be the main mind behind Russia’s victory over Napoleon.

Meanwhile, Napoleon’s Continental System, that served as the main reason for Napoleon’s onslaught on Russia, was ended by Russia as early as September 1812, when Alexander I published a manifesto on the resumption of trade relations between Russia and Great Britain.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox