What happened to the magnificent Romanov palaces after the 1917 Revolution?

Petrovsky Palace in Moscow.

Ivan Alexandrov/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ru; WM (CC BY-SA 4.0)Before the Revolution, the emperors and their numerous relatives lived in palaces built by the top architects in the world at the time. Most of the surviving palaces are in St. Petersburg, but you can also find royal family residences in cities that are now part of Europe and Asia. What has happened to them since they were nationalized and what still survives of the Russian Empire's architectural legacy?

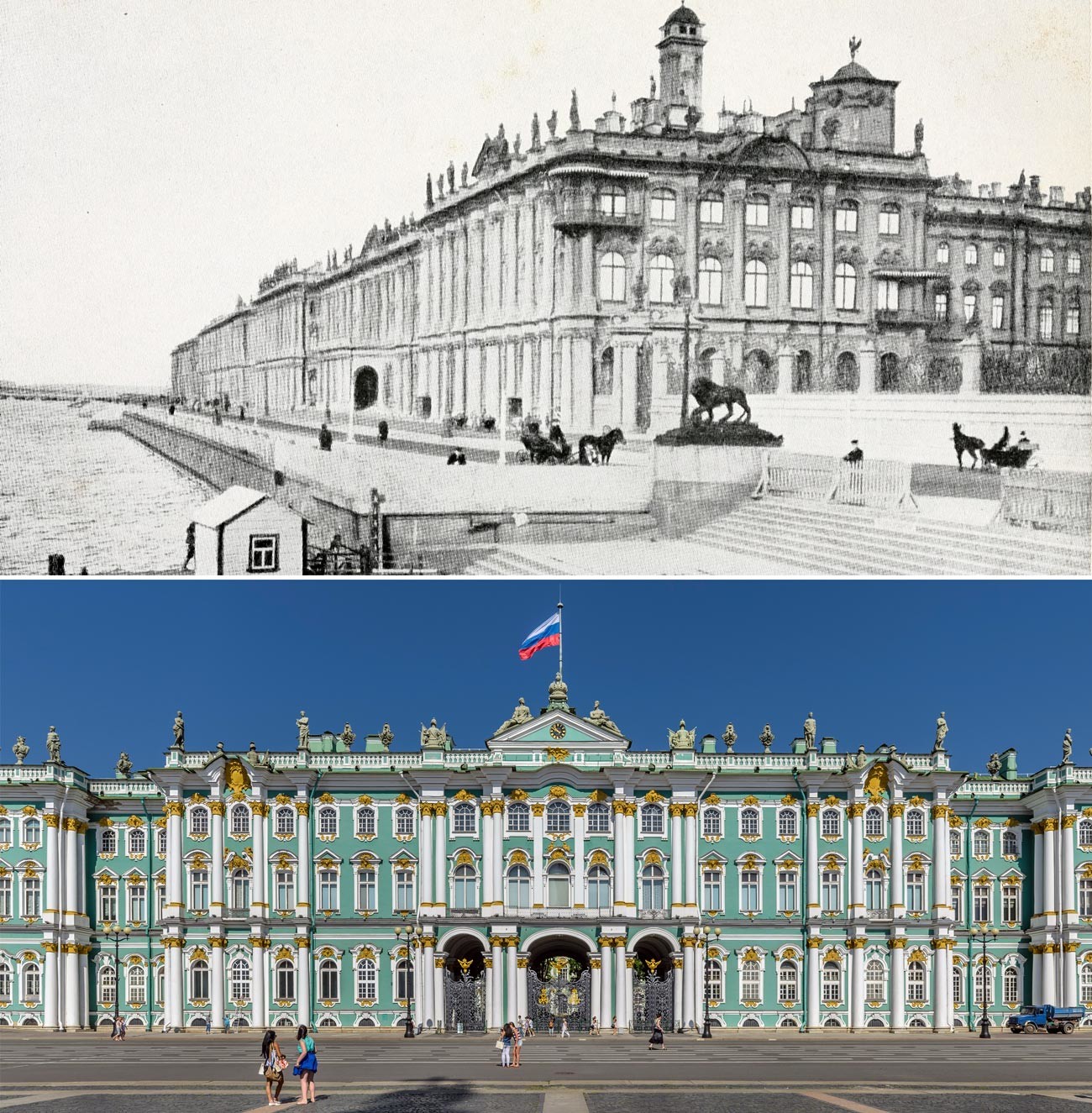

1. Winter Palace in St. Petersburg

Until 1904, the most famous Romanov palace served as the Emperor’s residence (which was later moved to Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo) and during World War I it housed a military hospital. The palace, which was built in the mid-18th century and designed by architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli, had more than 1,000 rooms. After the February Revolution of 1917, the Provisional Government housed itself in the Winter Palace, although this didn't last for long. By November, according to the Bolsheviks' version of events, the palace had already been stormed by revolutionary soldiers and sailors.

The Russian royal family in 1913.

Public domainIn 1920, the Museum of the Revolution opened here and, a year later, the huge halls of the Winter Palace were taken over by the paintings and art exhibits of the State Hermitage Museum—which had previously been located in the annexes of the palace. Today, the Hermitage is one of the most visited museums in the world.

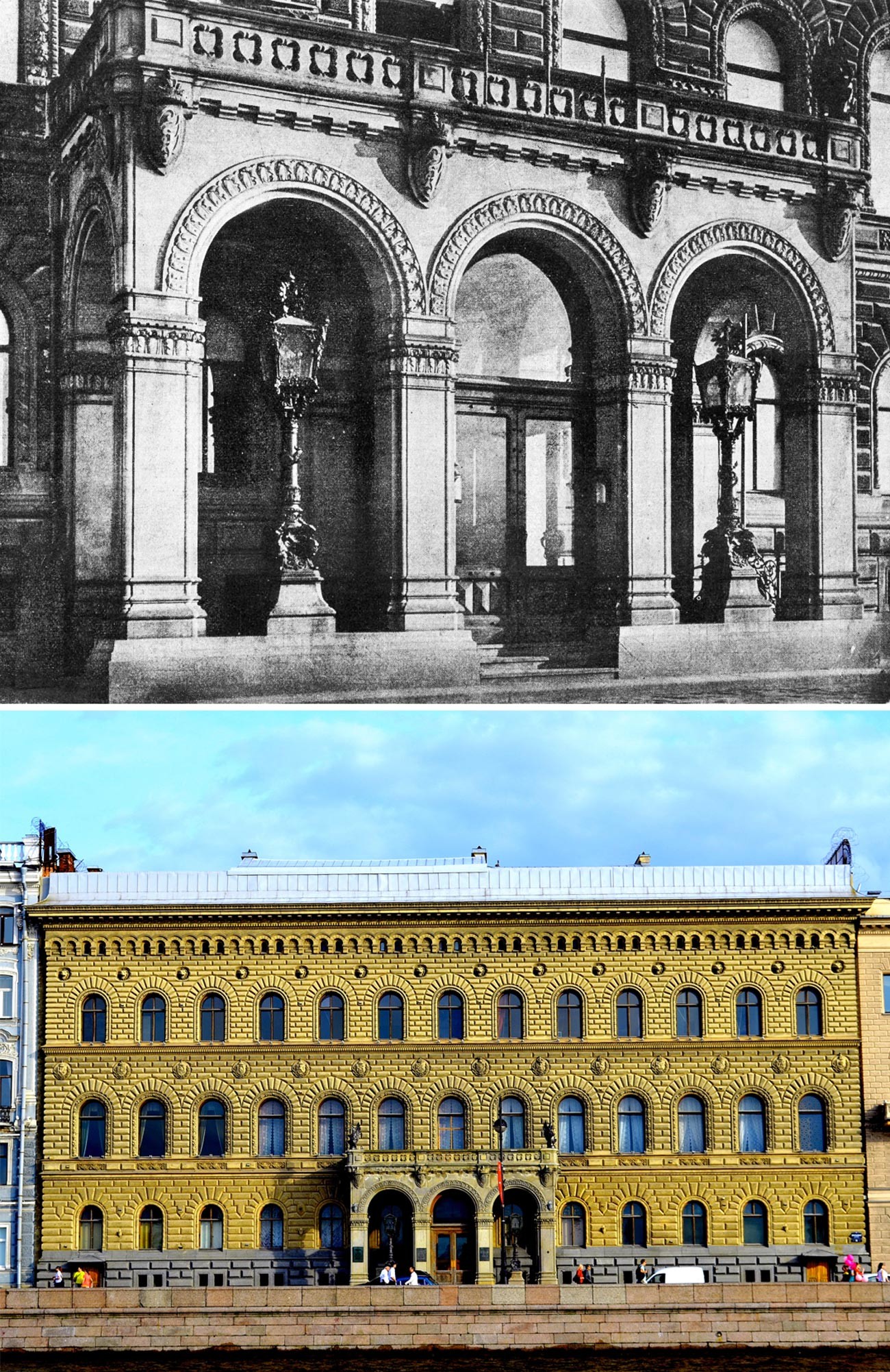

2. Vladimir Palace in St. Petersburg

There are two dozen Grand Duke’s palaces in St. Petersburg alone. Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna was one of the few representatives of the royal family who managed to flee abroad after the monarchy was overthrown (and even to smuggle her jewelry out of the country in the process). Her spouse, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich (Nicholas II's uncle), died in 1909, but Maria Pavlovna continued to live in their family palace on the Dvortsovaya (i.e. “Palace”) Embankment. The building, dating from 1870, was so luxurious that it was known as the "little Imperial court." Its exterior resembles an Italian palazzo.

Maria Pavlovna.

Public domainIn 1920, it became home to the House of Scientists, and nowadays you can visit it as a museum. Incidentally, old monograms with the Russian letter "V" (for Vladimir) have survived on the walls to this day, as have some of the original interiors.

3. Palace of Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna in St. Petersburg

The palace on the Moika Embankment was built as a wedding present from Nicholas II to his sister. The rooms were decorated with exquisite fireplaces, molded ceilings and oak panels with floral ornaments.

Xenia Alexandrovna, 1910.

Public domainIn 1919, the Lesgaft University of Physical Education moved into the building. The palace gates with the Grand Duchess's monogram are well preserved.

4. Anichkov Palace in St. Petersburg

The Anichkov Palace, built on a design by Rastrelli in the middle of the 18th century, is one of the oldest buildings on Nevsky Prospekt. Heirs to the throne and close members of the Imperial family used to live in the palace, and one of its last residents was Maria Feodorovna, mother of Nicholas II. The Emperor also spent much of his childhood here. Incidentally, Nicholas II liked the Anichkov Palace much more than the Winter Palace and continued to spend a lot of time there even after he came to the throne.

Maria Feodorovna, 1880s.

Public domainAfter the Revolution, the Imperial palace was turned into a Palace of Pioneers and today it is called the Palace of Youth Creativity. You can also visit it as a tourist.

5. Petrovsky Palace in Moscow

Apart from the Kremlin Palace, Moscow had another Romanov residence: Petrovsky Palace in the north of the city. It was originally built by the architect Matvey Kazakov at the end of the 18th century as a place where heirs to the throne arriving from St. Petersburg for their coronation could stay. The neo-Gothic palace resembles a medieval castle. Until recently it was closed to regular visitors. After the Revolution, it housed the Air Force Engineering Academy, one of whose graduates was Yuri Gagarin, before the palace was transferred to the jurisdiction of the city of Moscow in 1997. Only then was it restored and opened to visitors. Now everyone can not only see the restored interiors inside the building, but also stay for the night or take a stroll in the historic park.

6. Imperial palace in Tver

Another palace designed to serve as an imperial travel lodge is located in Tver. It too was founded in the mid-18th century and designed as a place where royal figures could stop over and rest. At the same time, a prince of imperial blood resided here on a permanent basis. The palace was the center of Tver's high society: literary evenings, balls and talks were all held here. In other words, it was a highly fashionable venue. After the Revolution, Tver's executive committee was housed in the building, and today a picture gallery can be found on the site. It is fascinating to study not just the pictures, but also the old architecture: the building itself, the stables, the ancillary buildings, the garden and the conservatory.

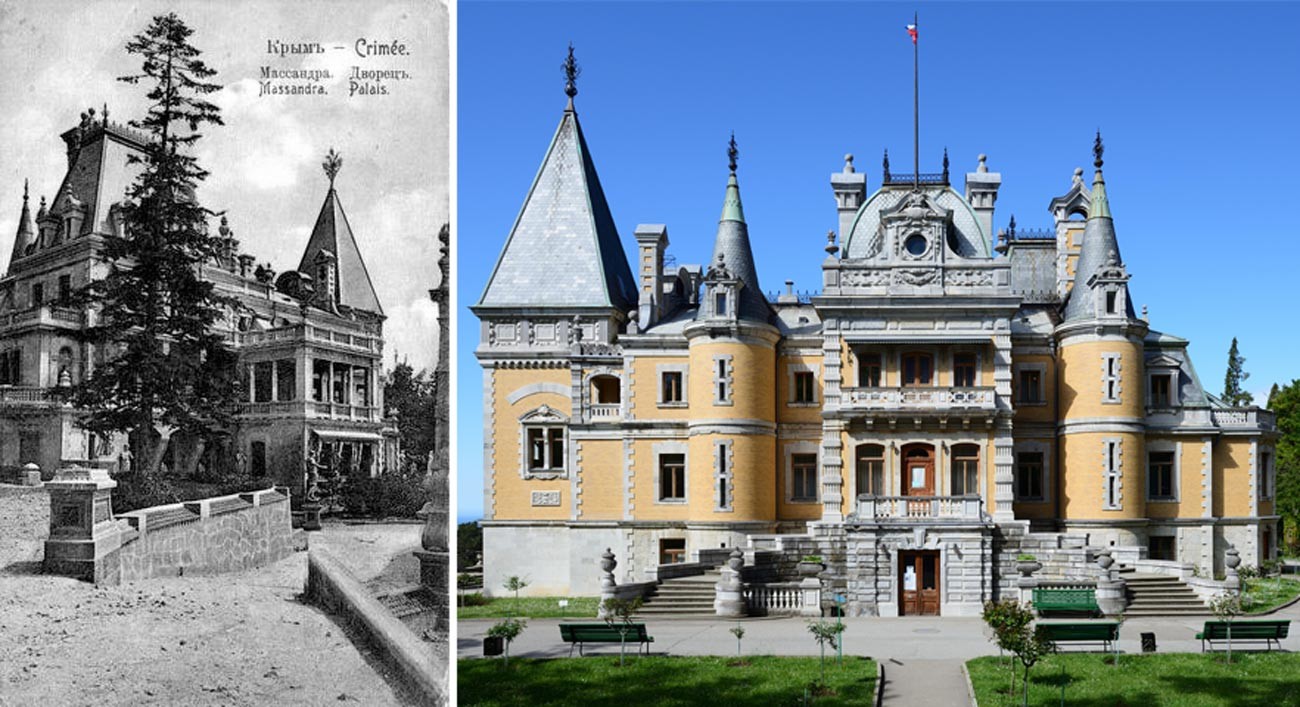

7. Alexander III's palace at Massandra

Crimea was traditionally the favorite holiday destination for the royal family and dignitaries from their close circle, and a number of architecturally notable mansions have survived here. The Massandra Palace, not far from Yalta, dates to the end of the 19th century and resembles a knight's castle. It is adorned with spired turrets, balconies featuring carved columns and "sphinxes" with female heads. At the same time, there are no formal state rooms.

Alexander III.

Public domainAfter the revolution and up until 1941, a tuberculosis sanatorium was located here. Subsequently it became a government dacha for Soviet leaders. In 1992, the palace became a museum (visits are usually combined with tastings of local wines). Only the window frames and floors remain from the original fixtures.

8. Livadia Palace in Crimea

The Romanovs' last palace was built for Nicholas II in Livadia in 1911, although it must be noted that he only managed to visit it four times. Naturally, Livadia could not compete with the Winter Palace. There were only 116 rooms and just a couple of annexes. At the same time, the building was very modern and had central heating, a telephone and even an elevator. The lighting scheme was also interesting. For example, the ceiling of the formal dining room did not have chandeliers. Instead, the architect concealed more than 300 lights around the perimeter of the room. Roundels with the initials of the Romanovs have survived, along with a massive entrance door and a white German grand piano on which Nicholas II's daughters used to play. A tourist route—called the Tsar's Path—passes through the grounds of the estate over around six km of picturesque views of the Black Sea and Yalta.

The Livadia Palace hosted the Yalta Conference of allied leaders in February 1945. Today a museum is located here.

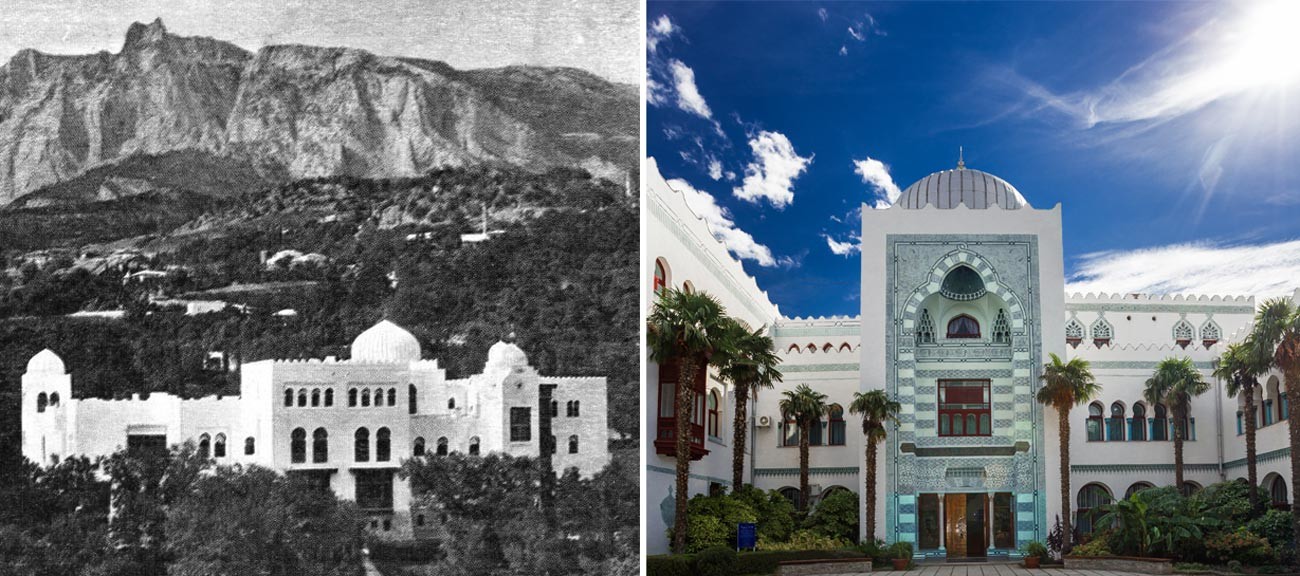

9. Dulber Palace in Koreiz

Looking at this palace, you almost start to believe you are somewhere in North Africa. Dulber was the residence of a grandson of Nicholas I—the Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich. It was built in the late 19th century by the architect Nikolay Krasnov, who designed the Livadia Palace, to plans drawn up by the Grand Duke himself, who had traveled much in the Middle East. The Moorish-style palace was adorned with silver-colored domes and quotations from the Koran. Other grandchildren of Nicholas I came to live at Dulber after the Revolution, including the grand dukes Alexander Mikhailovich and Nicholas Nikolaevich, as well as Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (mother of Nicholas II). In 1919, they left Crimea on board a British cruiser, and thus fled from harm's way.

Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich.

Public domainSoon after, the Dulber Palace was renamed the Red Banner Sanatorium, where party leaders came for rest and relaxation. Today the sanatorium is open to all.

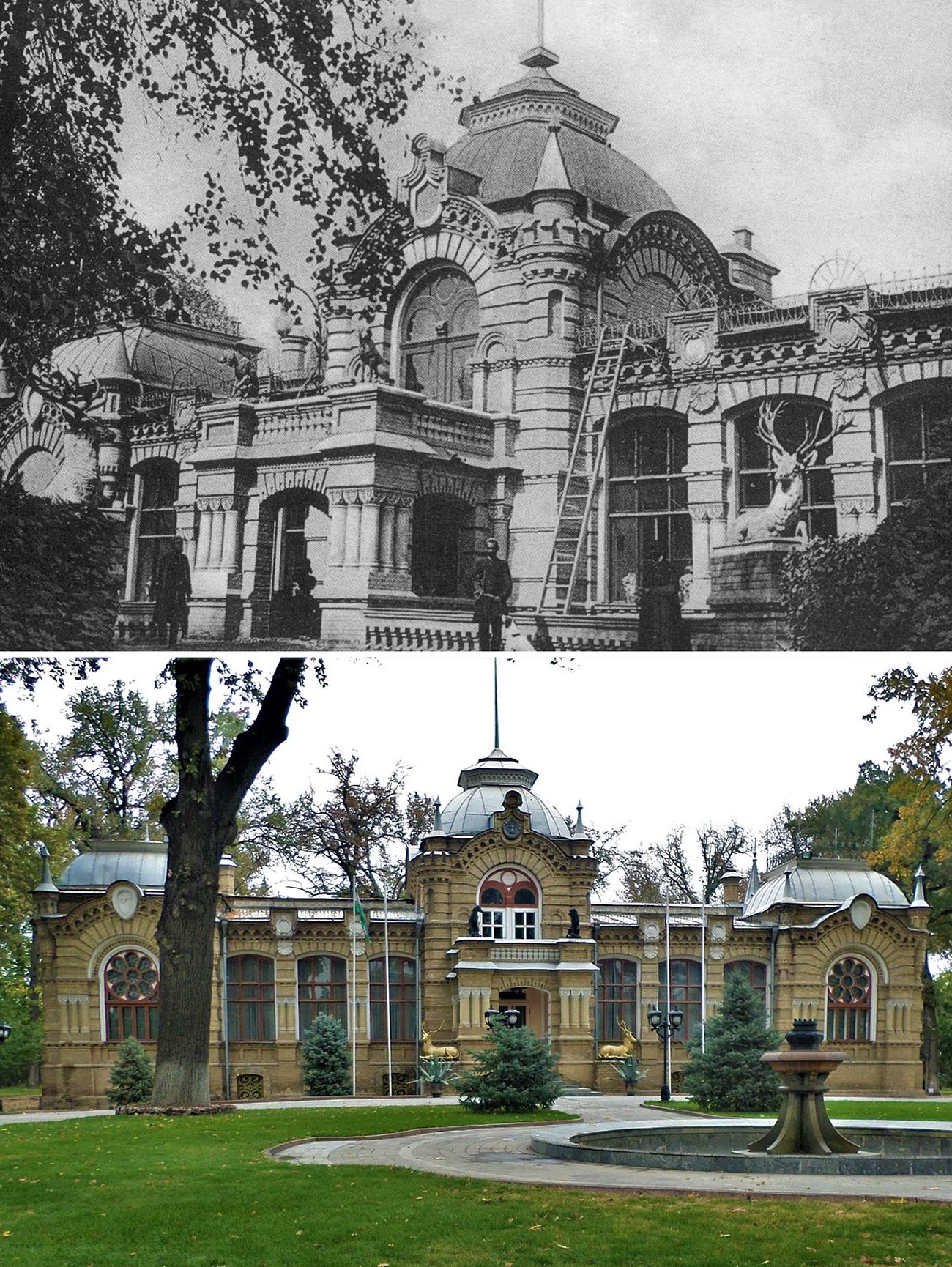

10. Palace of Grand Duke Nicholas Konstantinovich in Tashkent

Grand Duke Nicholas Konstantinovich, the younger brother of Emperor Alexander III, was sent away to Turkestan on the edge of the empire at the end of the 19th century due to a family scandal. In Tashkent (now the capital of Uzbekistan), he was allowed to build a palace. The extraordinary mansion constructed of baked brick in the eastern style has kept many of the original features, from a cast-iron spiral staircase to chestnut trees and oaks in the garden. The Grand Duke died of a pulmonary infection in early 1918 and left the palace to the city.

Nicholas Konstantinovich.

Public domainAfter his death, it housed a Palace of Pioneers and a museum of antiques. It has served as a Foreign Ministry reception building since 1992, but tours of the house are also available.

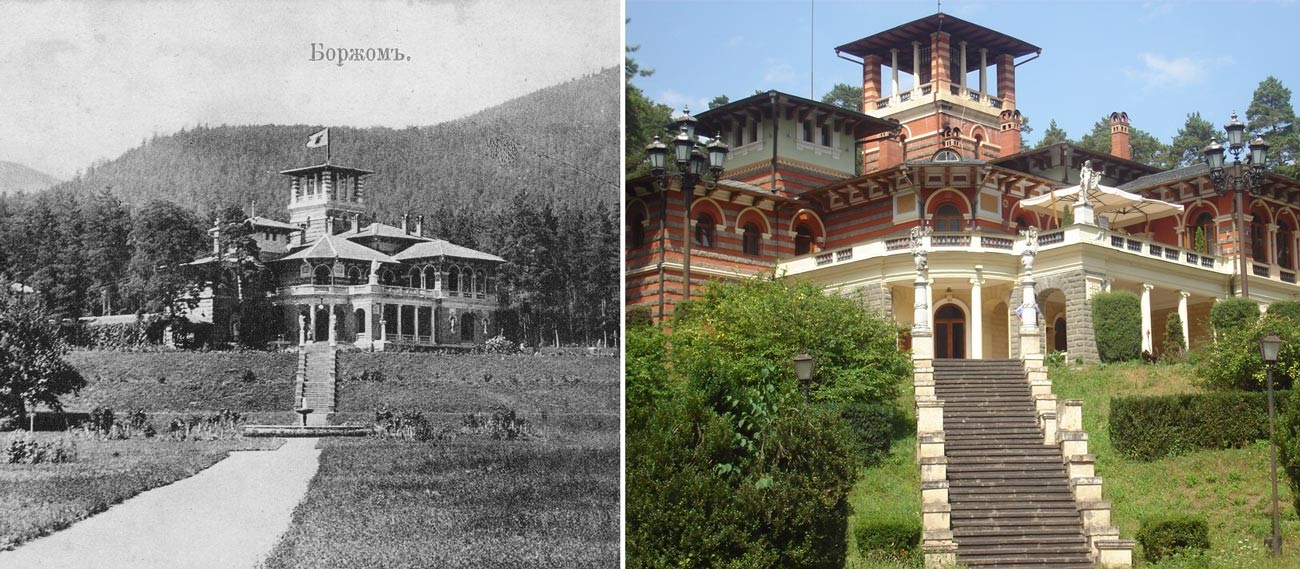

11. Palace in Likani, Borjomi

Nicholas I's grandson, Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich, was enormously wealthy and possessed a portfolio of properties that included St. Petersburg's Novo-Mikhailovsky Palace, several estates in various regions of Russia and this palace in Borjomi (today a resort town in Georgia) that he used it as his summer dacha. It dated from the late 19th century and was styled in the Moorish manner. A large park is laid out in the palace grounds and there is a mineral water spring. After nationalization, the palace in Likani became a government dacha for Soviet and subsequently Georgian leaders.

Nicholas Mikhailovich.

Public domainThe palace is a museum today. Even before the start of World War I, the Grand Duke himself foresaw the toppling of the monarchy in Russia. He died in the Peter and Paul Fortress in 1919 alongside his brother and cousins.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox