At the Russian North, late XIX-early XX century.

Public domainIn Orthodox tradition, it is mandatory to mount a cross on a grave. As a rule of thumb, it is a high eight or six-pointed cross with a lower slanted crossbeam. Four-pointed crosses are used by Catholics. So what does a cross “with a roof” or ‘golubets-cross’, as it is often called, mean?

A ‘golubets-cross’ is a grave monument in the form of a hut or with a symbolic “roof”. The word ‘golubets’ generally has two meanings in architecture. Firstly, it is a roof that protects the murals and icons on the facade of the church from bad weather.

This is how this roof looks like on the façade of the Moscow Kremlin's Assumption Cathedral.

Alexander Avilov / Moskva AgencySecondly, the word ‘golubets’ comes from the word ‘golbets’, which, in Russian log houses, means a wooden extension to the stove, where there is a descent into the cellar, closet or pit. People believed that a house spirit from the underworld, which guards the house, lived there. In a philosophical sense, the ‘golbets’ was a kind of portal to the afterlife.

You can see the golbets in the right corner of the photo taken in the Kizhi museum.

Yandex MapsThese structures were typical of Karelia and Arkhangelsk Region. You can take a look at them in the museums of wooden architecture (read more about them here).

Thus, these crosses symbolized the home of the deceased person. They were made exclusively of wood and, in some cases, both the roof and the pillar were ornately carved, while, in others, an icon was attached and the name and years of life were engraved.

The Old Believer cemetery, Kem (now Karelia).

Public domainThe history of these crosses goes back to the pagan burial rituals of the Slavic peoples.

When the deceased was buried in the ground, a so-called “izba of death” or a small log cabin was placed on the grave, filling it with supplies for the afterlife.

This also had a practical sense. Firstly, it was difficult to dig into the frozen ground (and the climate was just as harsh, if not harsher, a thousand years ago). And, secondly, this structure protected from wild beasts. It could have also been used as a hiding place.

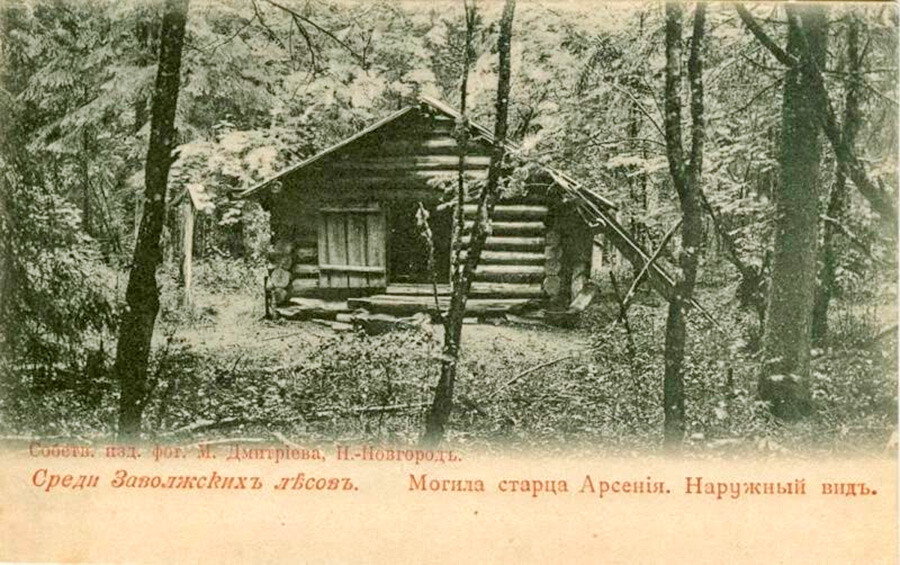

The grave with the izba.

Maxim Dmitriev/MAMM/MDFIn Russian folk tales, there is often an image of a “log house on chicken legs” ("izba na kuryikh nogakh"), where Baba Yaga lives - this is the house “on piles”, a symbol of the transition from the world of the living to the world of the dead. The word ‘kuryi’, in this case, comes from the word ‘kurny’ and not ‘kuriny’ (“of chicken”) and means “smoked”, a process which prevents the wood from decaying. Similar log houses exist in Scandinavia, as well.

The izba of Baba Yaga from Russian folks.

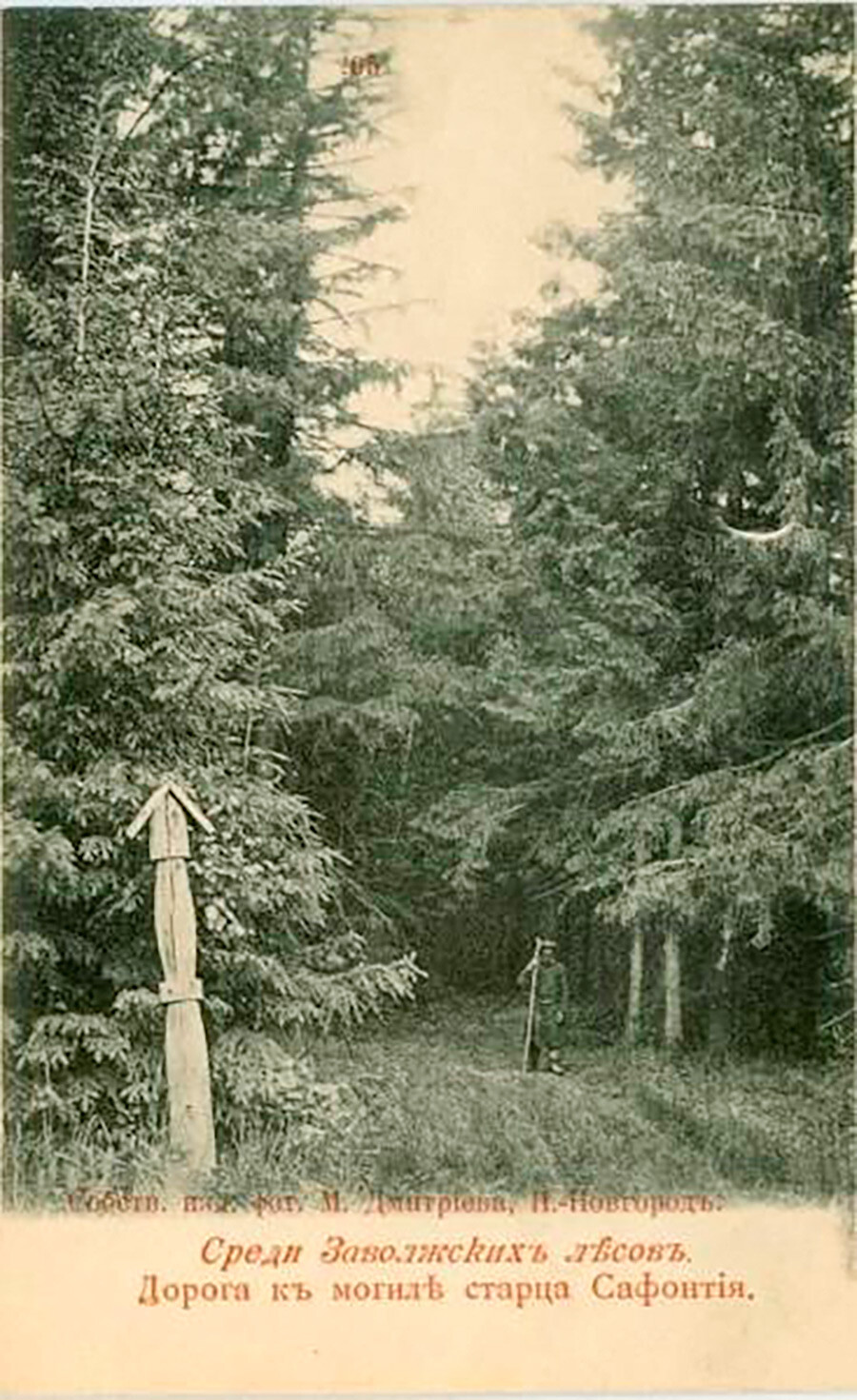

Ulyana Solovyeva/SputnikThe ‘golubets-cross’, on the other hand, is a smaller replica of an izba, which was placed both on the grave itself and by the road that pointed the way to the burial ground. As noted by architect Lev Dahl, who studied the phenomenon of these crosses: “Residents believed that they protected the village from evil spirits.”

A golubets near the road.

Maxim Dmitriev/MAMM/MDFIn addition to burials, some Slavic peoples (e.g. Vyatichi, Krivichi, Northerners) cremated the dead and placed vessels with ashes under the ‘golubets-crosses’. The roof protected the contents from snow and rain. Later on, cremation became unpopular, but the symbols of burial remained.

Vasily Perov. "Scene at the Grave," 1859.

Tretyakov GalleryAfter the baptism of Russia in the year 988, the church banned pagan rituals, although they have survived, in one form or another, to this day (like Maslenitsa or Red Hill Day). People started simply placing Orthodox icons or written prayers on top of traditional pagan crosses or attaching “roofs” on top of the Orthodox crosses. Today, these tombstones are associated exclusively with the Old Believers, that is, the people who did not accept the church reforms of the seventeenth century and were persecuted (read more about them here).

The golubets-cross, the town of Pushkin near St. Petersburg.

Messir (CC BY-SA)They retreated deep into Russia and began to live in remote villages where they simply could not be found. There, they placed such crosses, as they had been accustomed to do for centuries. That is why ‘golubets-crosses’ are best preserved in the villages of the Russian North that are far away from big cities. There are also a small number of them on the Volga, in the Urals and in Siberia.

And on top of churches in Novgorod, you can spot “Celtic” crosses. Find out how they appeared in Russia here>>>

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox