Craftsmen and artisans in the pre-revolutionary Russian village were necessary – but they also enjoyed an ambiguous reputation. In ancient times, making strong vessels from gooey clay, or forging tools from raw metal seemed a real miracle and the “authors” of such miracles were perceived as wizards and sorcerers.

In addition, millers and blacksmiths usually settled on the outskirts of the villages. It was these qualities, among others, that made the average Russian peasant afraid of them – the most interesting people in the Russian village.

A vodyanoy pulling a miller by the beard

V.MalyshevSince ancient times, Russians have believed that the miller is friends with evil, because he “works” with the leshiy (at the windmill) or vodyanoy (at the river mill). Millers themselves, when the wind broke the wings of the mill, believed that it was the “leshiy’s anger”. In addition, it was believed that the mill was home to small imps, which the miller had to appease with gifts. He allegedly would throw crumbs of bread and tobacco into the water and, on holidays, he ritually poured out vodka – for the water not to rise, the wheel not to break and not to jam, etc.

There is also information about sacrifices. “Old people said that when the miller’s wheels didn’t turn, he took a treat with him and went to visit the vodyanoy,” an Ural resident Mikhail Mazitov said in an interview in 1980. “They also say that when the mill didn’t turn, they threw a live rooster with a stone on its neck into the river and then the mill started turning again.”

'Old Mill' by Vasiliy Polenov

Vasiliy Polenov“The laying of the mill is accompanied by a ‘building sacrifice’ addressed to the water spirit [vodyanoy], which becomes the permanent patron of the mill, like a domovoy who must be presented with something to lure him into a new home,” writes Anna Petkevich in the article ‘Water sacrifice in Russian cultural tradition’.

Those who drowned at the mill or near the mill were also considered part of the mill’s “sacrifice”. Obviously, the mill was a very dangerous place. A miller could be mangled while repairing the wheel. It was also quite easy to drown, especially when tending to the underwater parts of the mill. It was believed that those who died in the mill were “taken away” by the otherworldly forces as a toll for the good work of the mill. After all, it was one of the main sources of the village’s welfare and income.

“My father used to tell me that when they build a mill, they bequeath several heads to the vodyanoy,” a 70-year-old Kabakova peasant woman from Alapaevsk said in 1976. “If you don’t make this oath, then he [the vodyanoy] will start drowning the cattle. My father said that when he built the mill, he bequeathed twelve heads – and twelve people drowned in total [near this mill].” Of course, no one specifically drowned people in the mill for sacrificial purposes – but the “substitute” sacrifice was usually black animals – dogs, sheep, roosters. They were kept right at the mill.

The miller’s occupation with such rituals supported his reputation as a sorcerer. His dwelling, the mill shed, was a forbidden place for girls, married women and especially children. Millers maintained their image. “Some miller was – biting all our ears, scaring us!” cites historian Tatiana Szczepanskaya the words of a resident of Yaroslavl Region. “And I was still a girl. He was such an old man – unintelligent. Did we annoy him or what? He just bit our ears!”

A Russian stove-naker

Public domainThere are many beliefs and rituals associated with the stove as the center of life in a Russian house. The stove didn’t only cook food and provide heat. It was believed that the stove healed from illnesses. Stove ashes were an obligatory component of ointments and decoctions. Accordingly, professional stove-men were highly respected. But, why were they feared?

To build a stove was not an easy job. The stove had to be sturdy, so as to not let out excess smoke, not howl in the wind and keep warmth well. Stovemakers’ work was not cheap, so they gave their profession a tough reputation. It was believed that one should never argue with the stovemaker to prevent him from bestowing trouble on a person.

A peasant hut with a stove

Vasiloy MaksimovA disgruntled stovemaker could mess up the owners’ lives so badly that they eventually bitterly regretted their stinginess. The stove’s defect would not even be visible. One could put splinters of wood under some of the bricks so that these places would pull air in and freeze. Leaving a slanting brick in a certain place in the chimney made the smoke go into the house. Finally, the most unpleasant thing is to “settle imps” or “plant a kikimora”.

The ‘kikimora’ was planted by embedding an empty bottle into the masonry of the stovepipe with the neck facing outward (and disguising the device). In a sufficiently strong wind from a certain angle, such an “instrument” made a wild howl. For “imps”, a goose feather with mercury in it or a flask with needles and mercury in it were used. Having walled up the “surprise” in the masonry of the pipe, the stovemaker, having demonstrated that the stove worked and having sat at the table with the owners (a mandatory “smoke meal” for the stovemaker), would leave. On the very first night, the stove would start howling and rattling (due to the movement of the cooling and heating mercury) and it would be impossible to sleep peacefully. The only thing that could fix it was dismantling the whole stove!

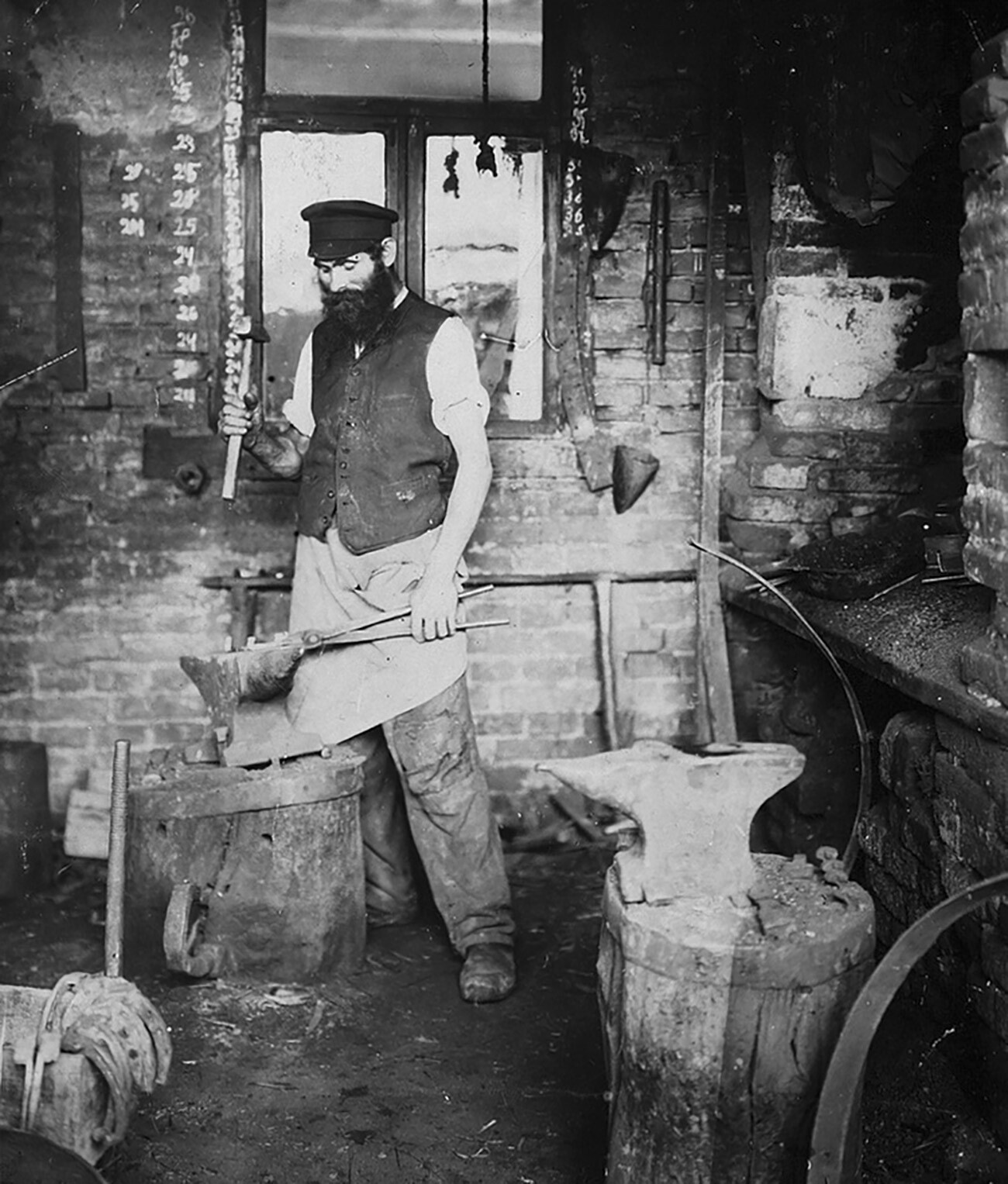

A Russian blacksmith at work

Public domainIf modern Russian muzhiks gather at the garage or a workshop in their village to discuss their muzhik topics (and get drunk), in pre-revolutionary villages, the role of such a “club” was performed by the village forgery. The blacksmith was in charge of horseshoeing and mending all metal tools and his skill with the horn and hammer made him a “wizard of the elements of metal”.

As the blacksmith shod the horses, it depended partly on him that the village’s harvest would be good. And, of course, it was the blacksmith who forged the wedding rings for the village newlyweds – this is why the notion of a strong and lasting marriage, which the blacksmith must literally forge for the bride and groom, is associated with his image.

"The Forgery" by Lavr Plakhov

Lavr PlakhovIn addition, the blacksmith is a frequent character of lovemaking incantations. One of them is cited by Tatiana Szczepanskaya: “As a good landlord’s blacksmith forges, he boils the iron, seals and welds the iron, so would the servant of God be sealed and welded for ages and ages.” In addition to the rings, a blacksmith could forge a horseshoe “for good luck”.

The smithy was a place of drinking, initiation of young men and fights. “In the blacksmith’s workshop, they drank, they fought all the time,” recalled a resident of the Vologda Region village of Zalesje. It was a forbidden place for women and especially for young girls, also because it was far away from the village (forgeries were built on the outskirts of the village for fire safety reasons).

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox