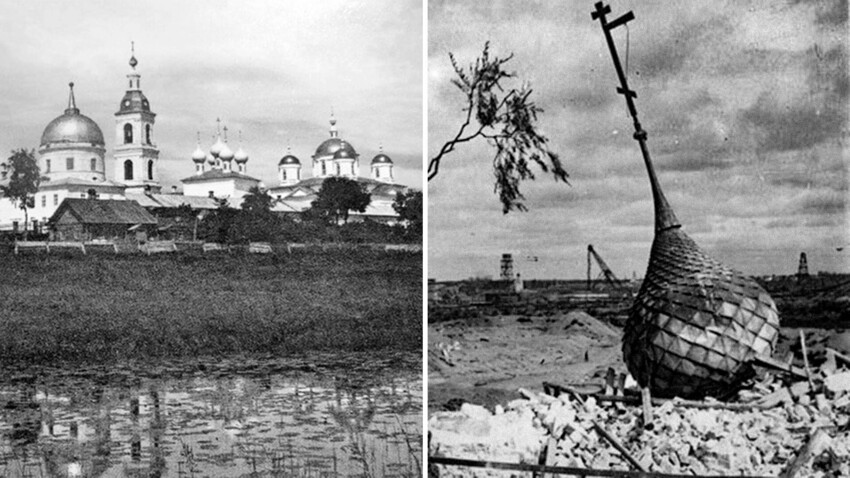

Mologa Afanafievskiy convent (L), remains of Mologa after the inundation (R)

Public domain

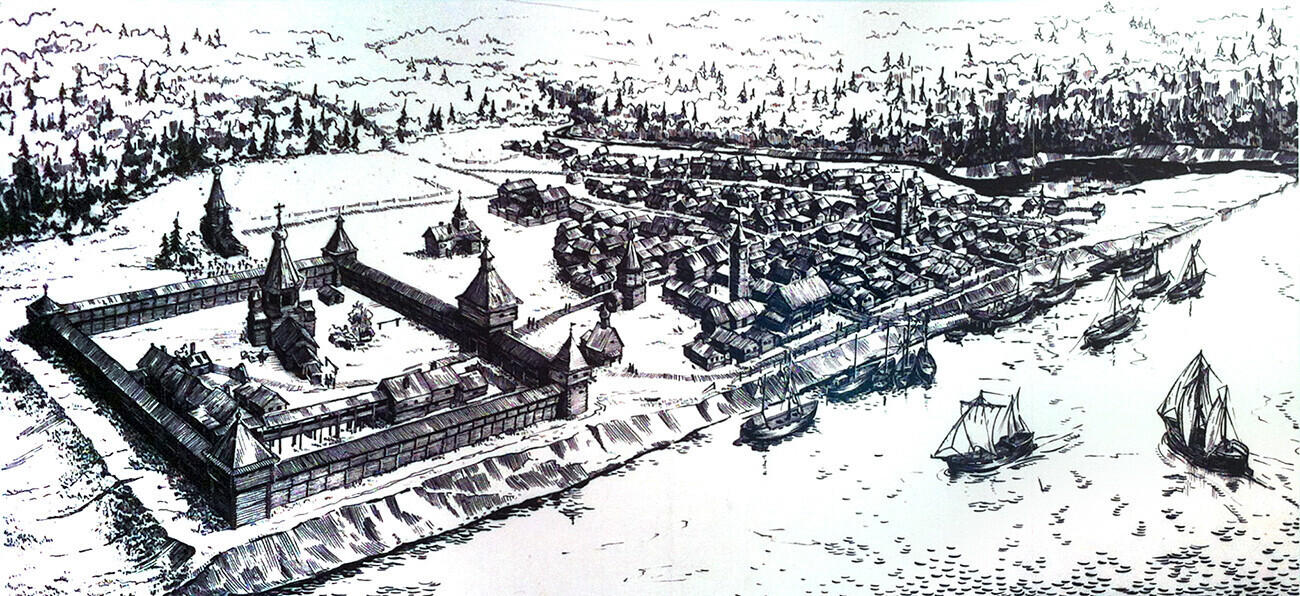

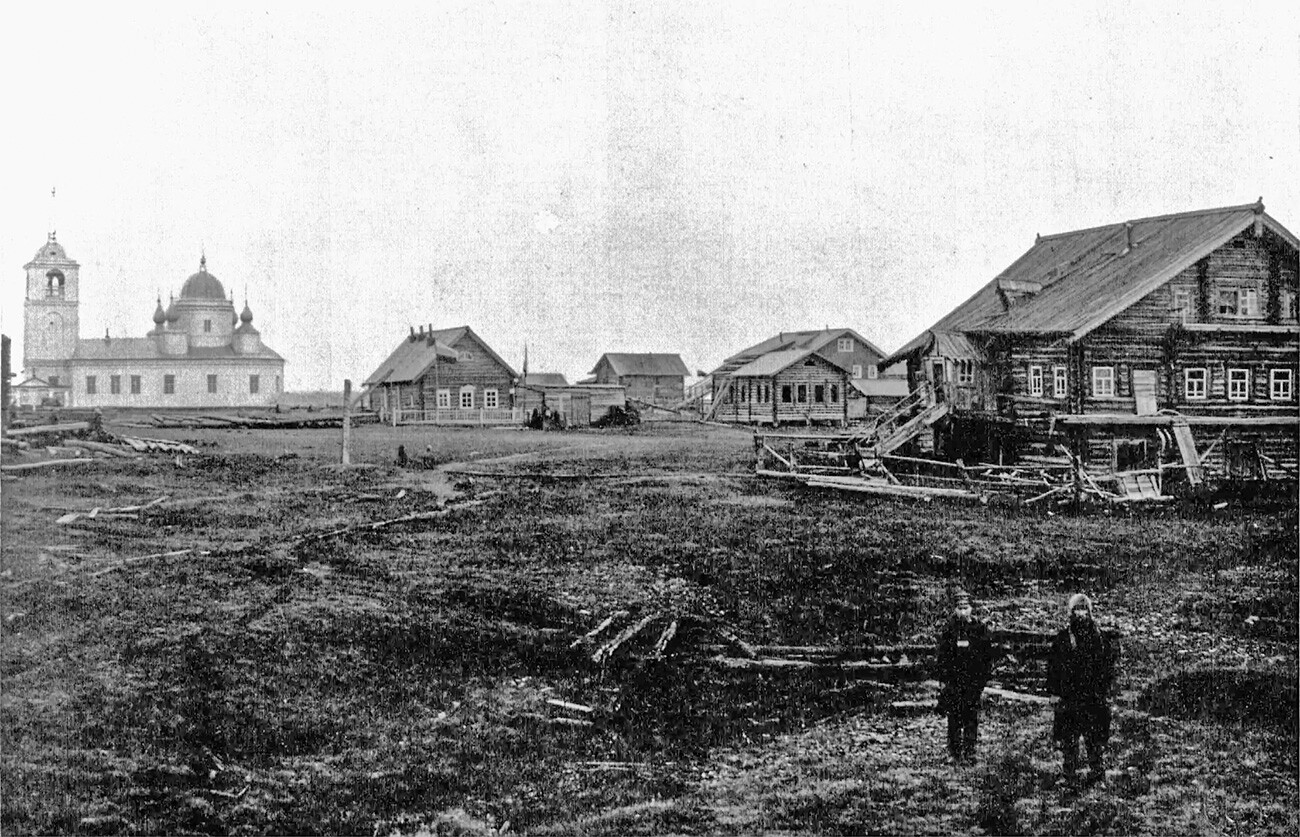

The Mangazeya ostrog with a settlement. Reconstruction based on M. Belov research

M. BelovThis city in the depths of Northern Siberia (in the region of today’s Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug) was founded at the end of the 16th century by the Russian state. The water route that led to it went through the northern sea passage and further along some rivers. The fortress in Mangazeya became the administrative center of the collection and storage of yasak – a tax levied on the local Siberian tribes that was paid in furs. Sable and fox pelts were sold to Europe for huge sums of money; so yasak was vital to the Russian state budget.

By the 1610s, Mangazeya was a fortress town with five towers, surrounded by a bustling trading city. Determining Mangazeya’s precise location was the goal of foreign spies who wanted to establish a trade route across the northern seas in order to then buy the plush sable and fox furs directly from the locals. In 1612, Dutch merchant Isaac Massa published a detailed drawing of Mangazeya, which meant he apparently somehow reached the city. This was disturbing news for the Russian tsar.

READ MORE: Why did Mangazeya disappear?

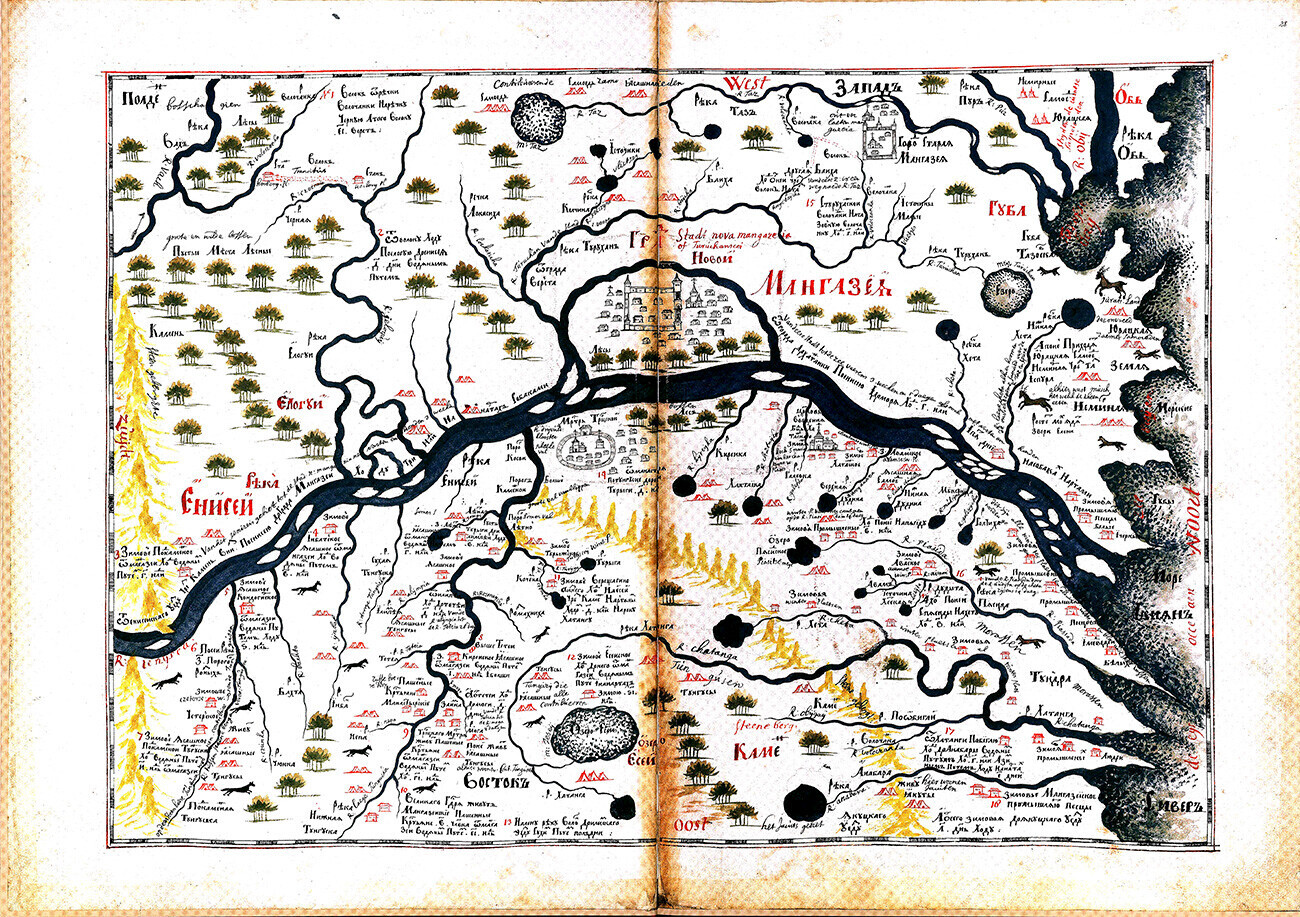

Map of Novaya Mangazeya (modern Staroturukhansk) with the surroundings of the late 17th century from the "Drawing Book of Siberia"

Semyon RemezovIn 1620, by the decree of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich the northern sea route, which led to Mangazeya, was closed and sentry posts were placed along the route to ensure security. The naval route to Mangazeya was now closed to outsiders, but the city was finally abandoned following a catastrophic fire in 1678, after which the remaining population was evacuated to Turukhansk, known as “New Mangazeya”. There, many of those people and their descendants lived until the 1780s. Only in the 20th century did archaeologists finally discover and determine the exact location of the original Mangazeya.

Phanagoria is Russia's largest archaeological monument of the ancient era, located on the Taman Peninsula. In the photo: excavations of the upper city. The upper city, or Acropolis, is the site of the original settlement.

Maria Plotnikova (CC BY 4.0)Phanagoria was the largest ancient Greek city on the Taman peninsula, spread over two plateaus along the eastern shore of the Cimmerian Bosporus. According to legend, it was founded in the 6th century BC, and nearly two centuries later it became the second capital of the Bosporan Kingdom – an ancient state with its capital in Panticapaeum (located on the site of the modern city of Kerch).

READ MORE: 5 ancient Greek cities you can visit... in Russia!

Phanagoria was so important that in the 7th century A.D. Byzantine Emperor Justinian II, who had been expelled from Constantinople, eventually settled here in exile. Phanagoria was a strategic city and transportation hub that helped to foster contact and trade between Byzantium and Great Bulgaria, an ancient state in the steppes north of the Black Sea. However, by the 11th century, due to the rising sea level, the city began to flood and its population was forced to migrate to the neighboring city of Tmutarakan.

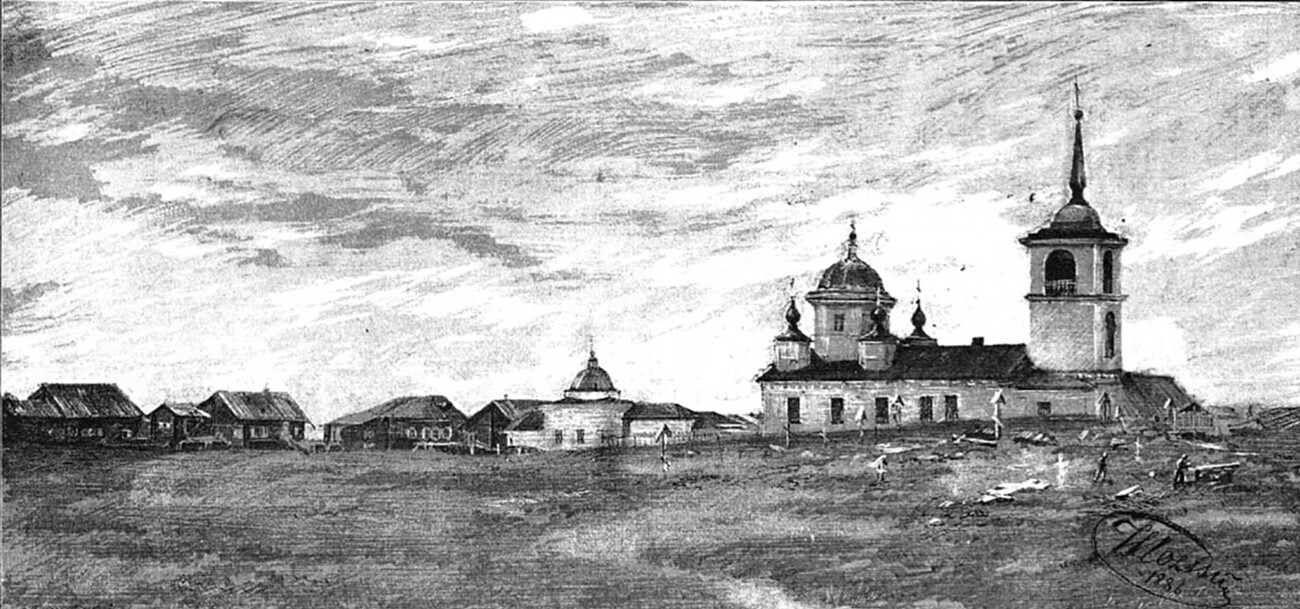

View of Pustozersk town in Arkhangelsk region, 1886

V. A. TolvinskyPustozersk was the first town that Russians built north of the Arctic Circle. Founded in 1499 on the orders of Moscow Grand Prince Ivan III, Pustozersk was located in the lower reaches of the Pechora River, which flows into the Pechora Sea. The town was built in a deserted area on barren soil, hence the name Pustozersk, which literally means "place of empty lakes." Its first settlers were military men and officials who were in the tsar's service. Since there was no arable land here, the main trades were hunting, fishing and bartering fur from local tribes. By the end of the 16th century the town was still small – about 150 houses and 500 residents.

What was left of Pustozersk by 1909

Public domainAfter the Livonian War of the 1580s, Russia lost the Baltic coast, and trade with Europe went through the northern ports, including Pustozersk. However, in the 1610s, English merchants started to appear here. In 1620, after the tsar’s decree to close the northern route for trade, the town’s population began to decline rapidly, and the fortress turned into a camp for exiles. For example, rebels who joined the uprising led by Stepan Razin, as well as those involved in the uprising in the Solovetsky Monastery, and others, ended up here. In 1682, the famous Old Believer, the Moscow arch-priest Avvakum and his faithful followers were burned alive in a wooden log cabin in Pustozersk.

An Old Believer cross marks the possible place where Avvakum (Petrov) was burned alive inside a log cabin in 1682

AAT (CC BY-SA 3.0)In the 18th century, Pustozersk lost its economic importance because a more convenient southern route to Siberia through the Urals had been discovered. Under Catherine the Great the fortress was finally dismantled and the town was abolished. However, people continued to live here until the 20th century, but in 1962, the last resident left Pustozersk.

The view of Mologa in 1900s

Public domainThe town of the same name on the Mologa River has been mentioned in historical chronicles since the 13th century. In the 14th century the town became the center of the independent Mologa principality. A little higher up along the river, in Kholopiy Gorodok, the largest Russian fair of that era was held – Molozhskiy Torg. It was so famous that it was frequented by merchants from all across Russia, as well as even Asia and Europe.

Over time, due to the shoaling of the Volga and other rivers, the fair was moved to Nizhny Novgorod. Mologa, however, continued to be a center of regional importance, and by the end of the 17th century there were 1,281 houses here. Twice a year a major fish fair was held, and the best fish were delivered directly to the Tsar's table.

The main square of Mologa during a city celebration

Public domainIn the 18th and 19th centuries the town gradually grew in size, and by 1896 there were about 7,000 inhabitants. At that time it had several factories, a treasury, a bank, a telegraph, a hospital and almshouse, post office and cinematograph, and an Orthodox convent. By the 1930s the Mologa region had a total population of about 20,000; with about 7,000 people residing in the town.

In 1935, the fate of Mologa was sealed, however, when the Soviet authorities decided to build the Rybinsk Hydroelectric Plant and Reservoir – the town and the surrounding areas with about 40,000 inhabitants were decided to be inundated as part of this effort to build infrastructure for the new Soviet state. The local inhabitants met the news with a defiant spirit, but over the course of the next six to seven years they were removed from the city, some forcibly.

The remains of the demolished buildings of Mologa after the inundation started

Public DomainREAD MORE: Why did the Soviets flood old Russian towns?

On April 13, 1941, flooding of the area began gradually and by 1946 the city was completely submerged. Even today, on every second Saturday in August, the descendants of Mologa meet and gather in Rybinsk to honor the memory of their submerged home. The meetings started in 1972 and are still held today. Sometimes, when the water level is low, the tallest buildings of Mologa protrude and create a haunting landscape of a vanished civilization.

"The Siege of Ryazan," 1969 by Yefim Deshalyt

Andrey Mironov (CC BY-SA 4.0)The modern city of Ryazan is actually the former Pereyaslavl-Ryazansky of olden days. The original Old Ryazan, which is first mentioned in the chronicles in 1096, was a large city, the capital of the Ryazan Principality. At that time, Pereyaslavl-Ryazansky was only a fortress on the borders of the Ryazan state.

Old Ryazan actively traded with other cities – the lands of Ryazan were rich in game and honey oak forests, while pottery and weaving crafts were well-developed in the city. In the 12th century, Ryazan even exported wheat through Novgorod to Europe. The city’s main fortress stood on a hill above the river, protected by steep ramparts and high walls with towers.

The site of Old Ryazan

Mikhey77777 (CC BY-SA 4.0)In 1237, the Mongol army of Batu Khan marched on Russia, and the Ryazan principality was the first area to take the blow of the invading army. The siege of the city of Ryazan lasted six days and nights; the Mongols outnumbered the Russian defenders many times over. When the Mongols finally stormed Ryazan, they killed everyone and everything inside, leveling the city to the ground. Although people subsequently returned to the site of the destroyed city, Old Ryazan's proximity to the steppe made it a vulnerable target for further raids.

The remains of an early 20th-century church on the site of the former Saints Boris and Gleb Cathedral of the Old Ryazan

Svklimkin (CC BY-SA 4.0)Therefore, by the 14th century, all the administrative and commercial functions of Old Ryazan, along with its population, were transferred 50 kilometers further north, to Pereyaslavl-Ryazansky, which we today know as Ryazan. On the site of the old city are the remains of the church that stand on top of those very ramparts that once tried to fight off the Mongol invaders in vain.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

Subscribe to our Telegram channels: Russia Beyond and The Russian Kitchen

Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter

Enable push notifications on our website

Install a VPN service on your computer and/or phone to have access to our website, even if it is blocked in your country

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox