At the bar of restaurant 'Caucasus'.

V.Chin-Mo-Tsai/SputnikThe majority of people believe that the USSR had no nightlife, but that’s not true. While night clubs and bars started to appear only during the late 1980s in earnest, they existed earlier as well, in other forms.

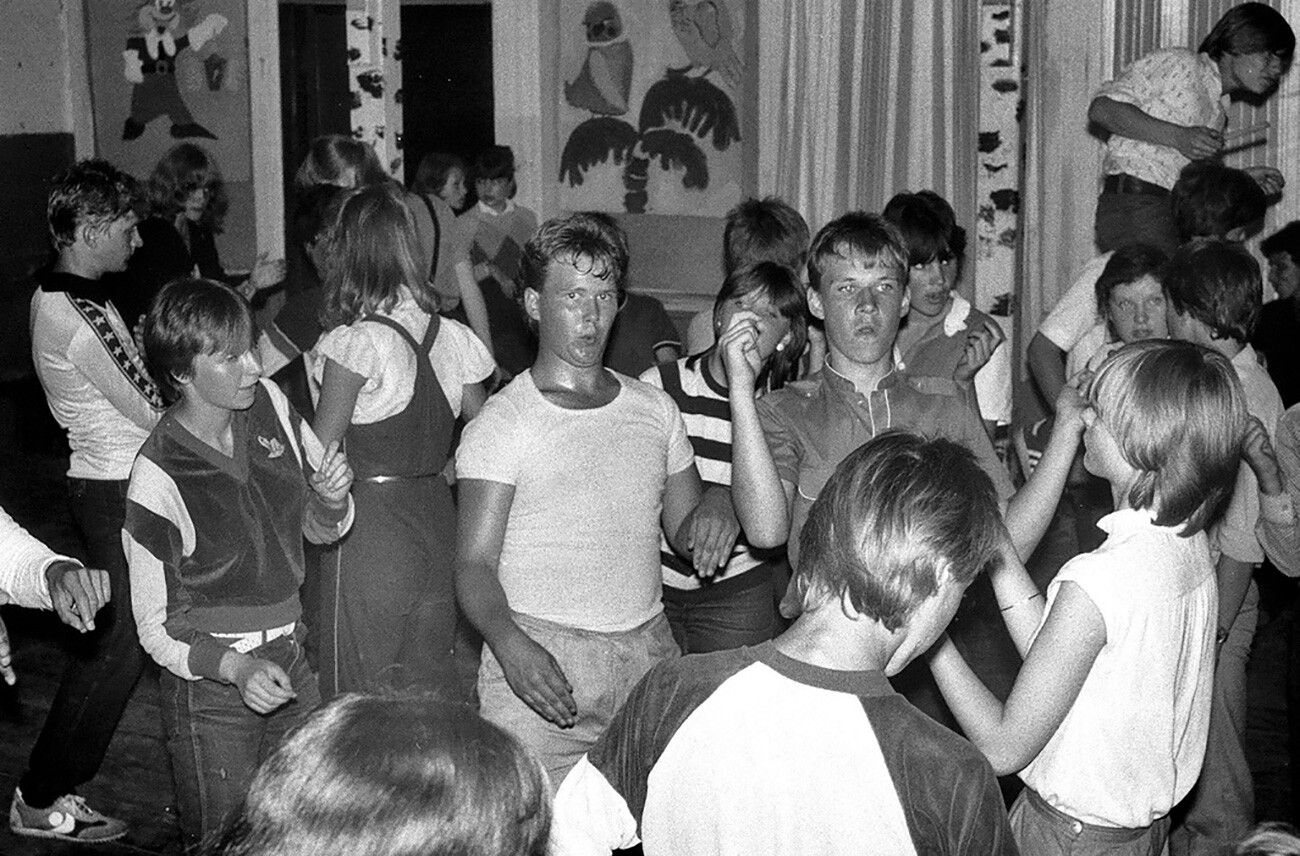

The main way to spend time for the majority of Soviet citizens was discos – although, it’s hard to categorize them as nightlife , since they usually ran between 7 and 11 pm on weekends. The very term “disco”, meanwhile, appeared in the USSR only in the late 1970s; before that, mass dancing was called precisely that – “dance nights”, or simply – “dancing.” And that’s what people did there - they danced: there were neither bars nor buffets there. However, despite the ban, some people did sneak in alcohol and consumed it in a secluded place to avoid getting caught by the police, which acted as security. A person could receive a stern talk from the police not just for alcohol consumption, but also for not paying the entrance fee - which was rather symbolic, but some still climbed the fence instead and sneaked onto the dance floor.

House of culture, 50s.

The state historical museum of the Southern Urals/russiainphoto.ruThe dress code was another important rule. People in tracksuits and even simply “untidy” clothes were not allowed into a disco. The untidiness was measured by the ‘people’s guard’ (volunteers who patrolled the disco along with - or instead of - the police); at discos in universities, that function was performed by a Komsomol guard squad.

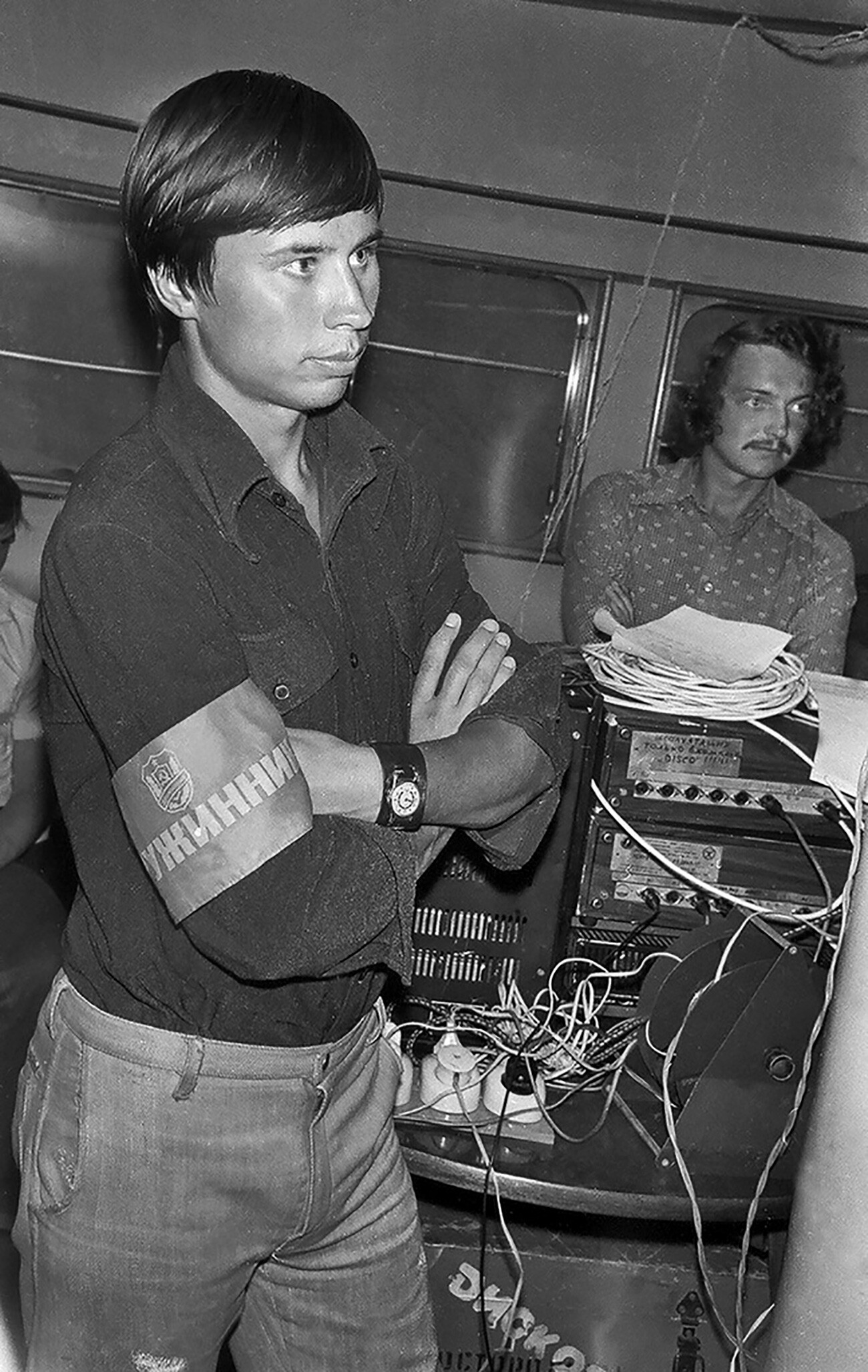

DJ and his security.

Pavel Sukharev/russiainphoto.ruDJs were not only playing Soviet music, but also foreign bands: ABBA, Boney M, Eagles, Ricchi e Poveri, Smokie, The Scorpions and so on. However, specific acts and songs were banned; by the end of the 1980s, even disco repertoire quotas were introduced: 70 percent of the songs had to be Soviet, 20 percent had to come from other socialist countries, and only 10 percent could be from capitalist ones. Some disco organizers managed to dodge the bans, but in doing so risked a shutdown.

At a disco.

Pavel Sukharev/russiainphoto.ruThere were also bars in the Soviet Union - but not for everyone. They were located in hotels for foreign tourists. “Bars in hotels for foreign tourists worked until 4 am. You could pay there only in foreign currency. And since a Soviet citizen was banned from possessing foreign currency, by finding themselves in such a bar, they automatically attracted the attention of the special services. I had this happen to me: some foreign movie guys came, I was hanging out with them at this bar. Suddenly, as I was already leaving, I was stopped and asked to show my papers. The fact that they bought me drinks and I didn’t pay for myself saved me,” our interviewee, who worked in the USSR as a translator and an attendant for foreigners, recalls.

Estonian SSR. An evening at a bar.

Alexander Makarov/SputnikCourtesans also flocked to such establishments. “Prostitution was banned in the USSR. All the girls reported their clients to the special services – that way, they had the opportunity to practice their craft. In the famous Leningrad restaurant Astoria (which existed back during tsarist Russia, and is still operating) there was a girl who arrived a bit tipsy every night. She walked around with an unlit cigarette, and men gave her a light. And she would size them up.”

Unlike the bars, Soviet citizens could still visit the restaurants at such hotels, using rubles as payment. But, few could afford a visit to such an establishment – the prices were steep. Even some foreigners preferred more modest hotels, farther from the city center.

Tourists in a hotel 'Dombay', located in the town of the same name in Karachay-Cherkess Republic.

B.Loginov/SputnikAnd yet, a bar for Soviet citizens did exist in the history of the USSR. Cocktail Hall was founded in 1938 in Moscow: the establishment occupied two stories and was built according to Western models. All the music that caused the irritation and distrust of the authorities could be heard there - jazz, tango, foxtrot etc. The cocktail menu included some 500 items – all prepared from domestic alcohol; roasted salted almonds, olives, and canapé were served as snacks. Foreigners were its main audience, along with dissidents and “golden youth” – the worship of Western culture was alien to a regular Soviet person, and the prices were also very steep. For example, in 1961 one cocktail cost 4 rubles and 10 kopecks; a travel pass for a month, for all types of transport and with unlimited rides, cost 6 rubles.

Cocktail hall.

Archive photoDuring Stalin, Cocktail Hall was a mousetrap for dissidents – the establishment gathered them all in one place, helping the state security services. In 1968 the bar was shut down, with an ice cream cafe opened instead. A similar bar existed in Kiev, as American writer John Steinbeck, who visited the USSR in 1947, mentioned in his Russian Journal. Steinbeck remembered that all the drinks tasted strongly of grenadine – pomegranate syrup. Because of this syrup, all the cocktails were also pink.

Bar culture then was more of a people’s initiative, only barmen working at hotels for foreign tourists had access to foreign recipes and alcohol. Working at a bar became a real profession thanks to enthusiast Alexander Kudryavtsev – who is considered the first Soviet barman. In 1978 he released the first Soviet recipe book for cocktails – The Technology of the Preparation of Mixed Beverages, which his colleagues would take notes from.

A disco at the Olympic village.

Boris Kavashkin/TASSDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox