Tsarist splendor: 5 secrets of St.Petersburg’s main park

St. Petersburg impresses with its atmosphere of Russia’s imperial past: Wide streets, imposing buildings, picturesque bridges

1. Peter the Great was inspired by the park at

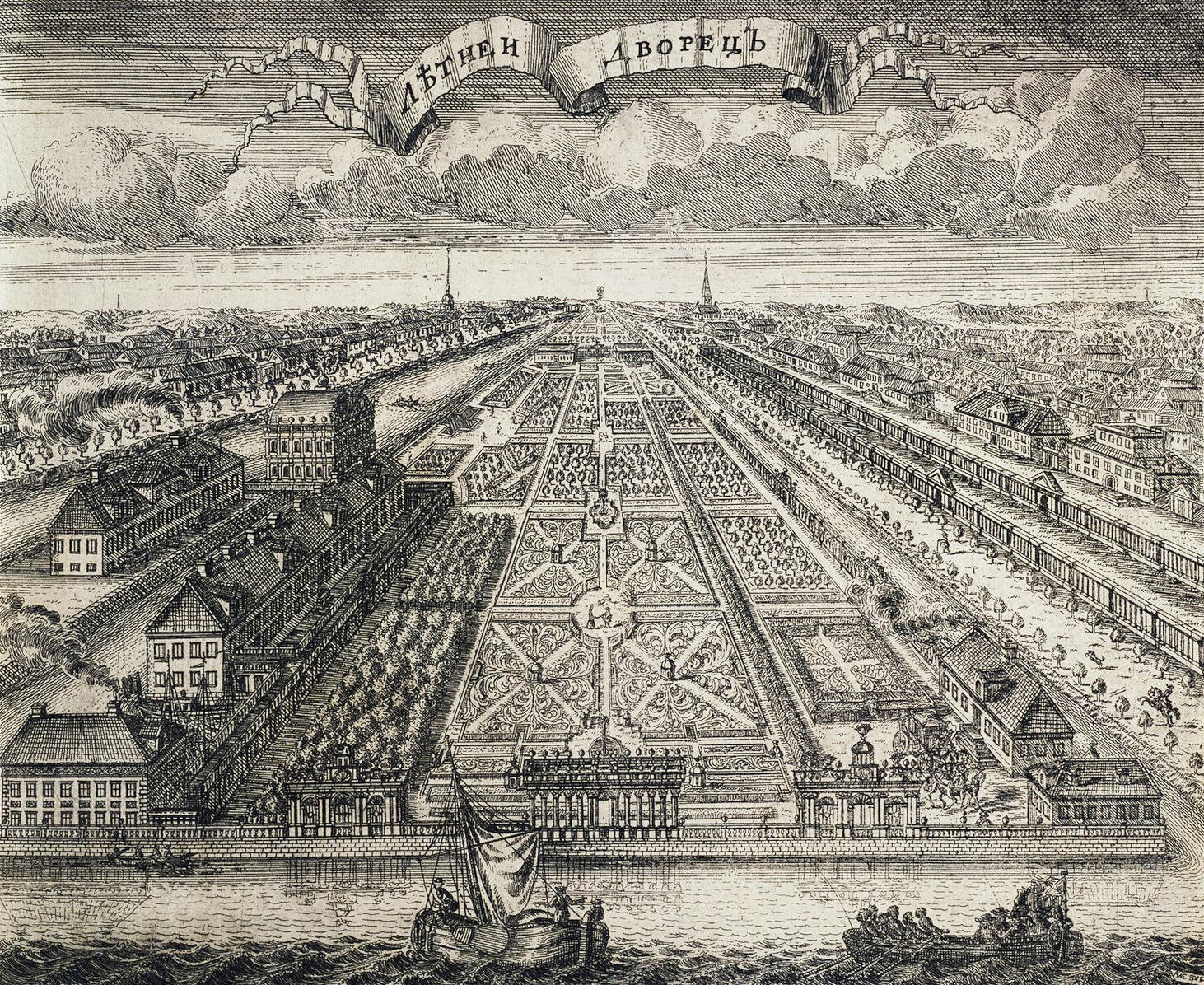

Summer House and Summer Garden in St. Petersburg, 1716.

Alexey ZubovAccording to the rules of elegant gardening, the park’s alleys were planted with evenly trimmed shrubs. The four sides bordered by these “green walls” were filled with garden decorations: Ponds, fountains and Italian marble sculptures.

At first, one could visit the park only by personal invitation of Peter the Great, but

2. The iron fence impressed a British lord

One romantic legend says that a British lord visited the city during the White Nights. His ship sailed up the Neva and docked near the Summer Garden. Charmed by the majestic beauty of the park the lord refused to come ashore, saying that this would be pointless because he’d never see anything more beautiful.

“I saw everything I wanted to in St. Petersburg: The fence of the Summer Garden during White Nights," he

Believe it or not, but the wrought iron gates and fence still look impressive! The fence, which was decorated with gold-plated flower petals, was partly made in the 1780s in the city of Tula, which was famous for its artisans

3. The name, Summer Garden, has nothing to do with

4. The first art gallery opened

5. The Summer Garden is part of the Russian Museum

According to Peter’s wishes, the Summer Garden was to be not only as a place of rest for city

The only structure preserved in the garden since Peter’s era is the Summer Palace built in 1710-1712 by Trezzini.

In 1934, the park with its huge collection of marble sculptures, the Summer Palace and the house of Peter the Great were given museum status. Soviet architects studied the historic buildings and its galleries, and the sculptures were restored. Now, the Summer Garden is an official branch of the State Russian Museum.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox