Exploring the Stroganov Baroque in the Russian North

Solvychegodsk. Cathedral of the Presentation, southwest view. Left: recreation of log stockade tower from Stroganov compound. March 8, 1998

William BrumfieldSituated on the south shore of White Lake (Beloye ozero), the small port of Belozersk is in a pivotal position between the Volga River Basin and Lakes Onega and Ladoga. In the summer of 1909, Russian chemist and photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky visited the town as he traveled along the Mariinsky Waterway, connecting St. Petersburg with the Volga River Basin. My work in the area began in the 1990s.

Belozersk. Bell tower & Church of the Icon of the Most Merciful Savior, southwest view. June 9, 2010

William BrumfieldBelozersk’s 18th-century prosperity was reflected in the construction of numerous parish churches, including the beautiful Church of the Merciful Savior (Vsemilostivy Spas), dedicated to an icon of the Savior revered for its protection of Russia. Located near the lakeshore, the Savior Church on the Canal (as it is also known) was originally built in 1716-23 and reconstructed two years after the 1753 Belozersk fire.

Belozersk. Church of the Icon of the Most Merciful Savior. Icon screen. Summer 1909

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyThe Savior Church appears in three of Prokudin-Gorsky’s evocative photographs, and he also photographed the interior with its carved icon screen. Focusing on the Royal Gate at the center of the screen, his photograph conveys the exuberance of the decorative arts in the Russian North.

Unfortunately, this delightful screen was destroyed when the Savior Church was ransacked during the Soviet period, but others in the Russian North survived. Some of the most splendid can be found along or near the Northern Dvina River. Originating near Veliky Ustyug, the Northern Dvina empties into the White Sea near the port city of Arkhangelsk.

The town salt built

Among the many treasures in the Russian North, few are as improbable as the town of Solvychegodsk, located on the north bank of the Vychegda River not far from its confluence with the Northern Dvina. Despite its sleepy appearance and declining population (now under 1,900), Solvychegodsk contains two of the most elaborate examples of religious architecture and applied arts in all Russia.

The first Russian settlements in the area probably arose in the 14th century with the support of Novgorod, whose explorers would have recognized the value of a site near the crossing of two major river routes: north to the White Sea and east to the Urals. As Moscow expanded during the 16th century, the northern river network became a crucial transportation artery for trade.

Wealthy entrepreneurs such as the Stroganovs, who arrived in the middle of the 16th century, received privileges from the Muscovite state to establish and maintain settlements in the area. The main source of their wealth was salt, which in the medieval era was one of the most valuable of commodities.

Solvychegodsk means "salt of the Vychegda," and the area is replete with salt springs, as well as a small brackish river, the Usol, and a saline lake, the Solonikha. The Stroganovs created a salt monopoly there that brought them enormous wealth, and Solvychegodsk became the center of a private empire.

The patriarch of the dynasty, Anika (Ioanniky) Stroganov (1497-1570), began the lavish Stroganov patronage of the arts. His wealth was incalculable, from salt refining, trade and the exploration of Siberia. Ivan the Terrible allowed Stroganov to maintain an army of his own and to exploit the wealth of vast areas of the Urals and Siberia, greatly expanding the domains of the tsar at relatively small expense.

A distinctive look

Solvychegodsk. Cathedral of the Annunciation, northwest view. June 26, 2000

William BrumfieldAnika Stroganov's primary contribution to Russian architecture is the Annunciation Cathedral, begun in 1560 and apparently completed in the early 1570s, although it was not formally consecrated until 1584 (the year of Ivan’s death). Its design is unusual as it has only two interior piers, yet it has the five cupolas usual for major 16th-century churches.

Cathedral of the Annunciation. Icon screen. June 26, 1999

William BrumfieldThe structure originally culminated in arched gables whose outlines are still visible beneath a four-sloped 18th-century roof. The original bell tower at the northwest corner was replaced in 1819-26 by an oversized neoclassical bell tower.

Cathedral of the Annunciation. Icon screen, Royal Gate (entrance to main altar). June 26, 1999

William BrumfieldThe interior walls of the Annunciation Cathedral were painted with frescoes in the summer of 1600, as noted in an inscription at the base of the walls. They were subsequently overpainted in the 18th and 19th centuries, particularly after a fire damaged the interior in 1819. A restoration effort ongoing since the 1970s has uncovered original frescoes on the west wall and in certain other areas.

Cathedral of the Annunciation. Interior, northwest corner & north pier. June 26, 1999

William Brumfield

Cathedral of the Annunciation. West wall frescoes, Last Judgement with depiction of sinners in hell. June 26, 1999

William BrumfieldThe centerpiece of the Annunciation Cathedral is an elaborate five-tiered iconostasis, originally installed by the end of the 1570s. Its present form dates from the 1690s, although the Royal Gate that opens to the altar was donated by the Stroganovs at the beginning of the 17th century.

Cathedral of the Annunciation. Diaconicon (right part of apse). Ceiling fresco of Passions (martyrdom) of the Apostles, with Christ in the center and Christ crucified beneath image of Lord God Sabaoth. June 20, 2000

William BrumfieldEpitome of the Stroganov style

Solvychegodsk. Cathedral of the Presentation, southwest view. July 17, 1999

William Brumfield

Solvychegodsk. Cathedral of the Presentation, northeast view. William Brumfield. June 26, 2000

William BrumfieldThe florid style of the Stroganov school of religious art culminated with the late 17th-century church at the Monastery of the Presentation of the Virgin (founded in 1565). Its patron, Grigory Stroganov, acquired a dominant position in the Stroganov mercantile empire and soon figured prominently in the political and cultural changes effected by Peter the Great.

Cathedral of the Presentation. West facade with ceramic panel. June 26, 1999

William BrumfieldIn 1688, he commissioned a large brick cathedral to replace a wooden one at the monastery that formed part of the family compound at Solvychegodsk. Although the church was not consecrated until 1712, some of the lower parts of the structure were already functioning by 1691, and the basic construction was completed by 1693.

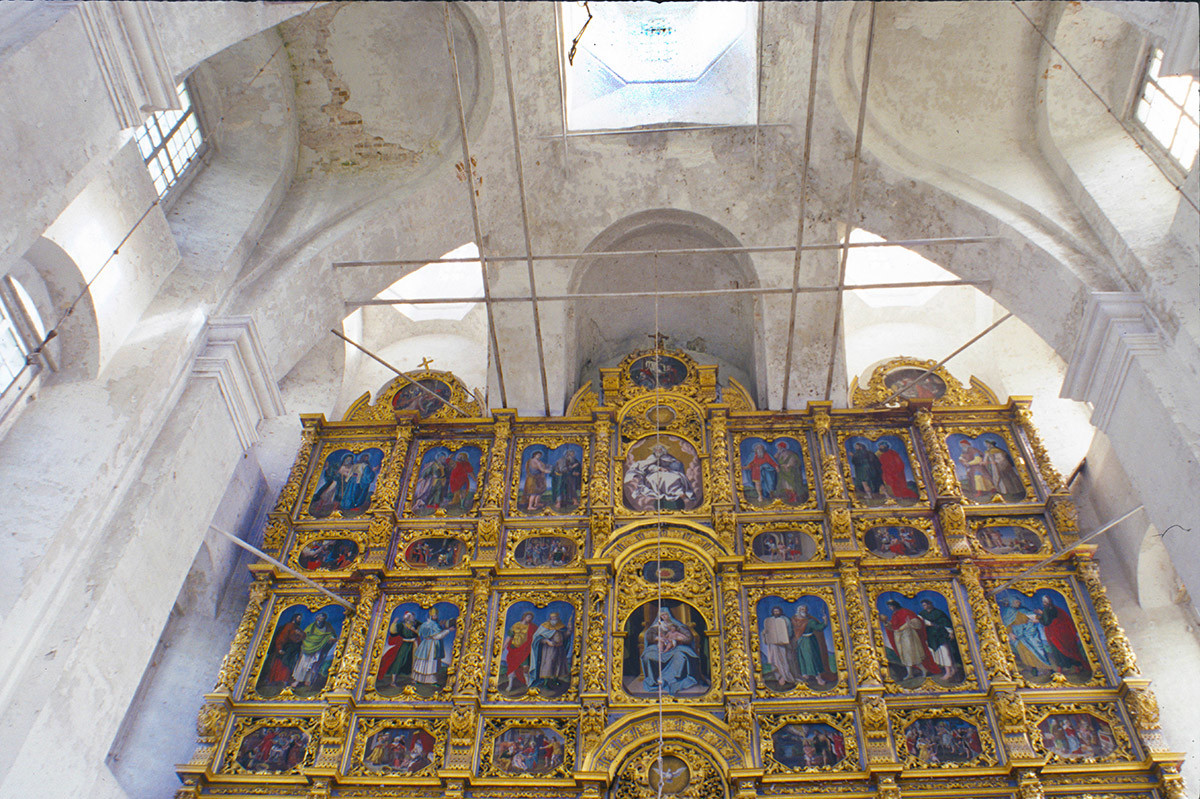

Cathedral of the Presentation. Icon screen. June 26, 1999

William BrumfieldThe Presentation Cathedral is distinctive for many reasons, not the least of which is the carved limestone decoration on the brick facades, which are also decorated with polychrome tiles. During the 18th century, the gallery – originally an open terrace – was enclosed in a brick arcade with an intricate limestone cornice (now partially obscured).

Cathedral of the Presentation, southwest view. March 8, 1998

William BrumfieldThe soaring interior of the Presentation Cathedral is created by a vaulting system of paired arches that support the large structure and its five cupolas with no free-standing piers. The effect is one of bright spaciousness, intensified by the lack of frescoes.

Cathedral of the Presentation. Upper tiers of icon screen & ceiling vaults. June 26, 1999

William BrumfieldAll attention is focused on the elaborately carved seven-tiered iconostasis created by Grigorii Ivanov in 1693. The icons within the Presentation Cathedral were painted on canvas instead of treated boards in a western style by a Stroganov painter, Stepan Narykov.

Cathedral of the Presentation. Icon screen with Royal Gate. June 26, 1999

William Brumfield

Cathedral of the Presentation. Icon screen with icon of Apostles Andrew & James. June 26, 1999

William BrumfieldDecline and rediscovery

As new trading routes led to a decline in its significance in the 18th and 19th centuries, the town became a small resort, known for its mineral waters and springs. Curiously, Solvychegodsk was also subsequently used by the tsarist government as a place of exile.

The local Museum of Political Exile, established in 1934, includes a log cabin where Iosef Dzhugashvili (Stalin) spent some of his many northern exiles – in 1909 and again in 1911. One can only imagine his impressions of the grand Stroganov cathedrals, emblematic of a social and political system that he was dedicated to overthrowing. Contemporary accounts portray Solvychegodsk as a dreary, poverty-stricken backwater.

Political Exile House Museum. Iosif Dzhugashvili (Stalin) briefly lived here. July 28, 1996

William BrumfieldThe Soviet period inflicted much damage on the cultural heritage of Solvychegodsk. Of the town’s 12 brick churches at the beginning of the 20th century, eight were destroyed and two others left in ruined state. Ironically, the lavish jewels in the crown, the two Stroganov "cathedrals," were spared (including their interiors) and still stand in monumental glory.

In the early 20th century, the Russian photographer Sergeн Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France where he was reunited with a large part of his collection of glass negatives, as well as 13 albums of contact prints. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox