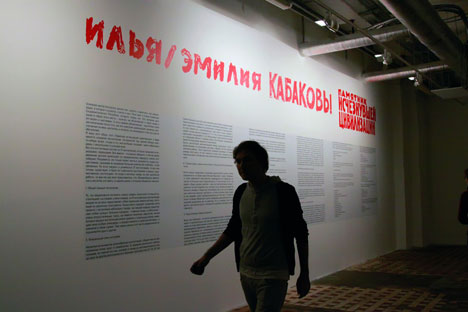

At Red October, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov explore a society that no longer exists

Ilya Kabakov, one of the most heralded artists of our time, came to New York in 1987, an illustrator and artist in his 50s who had never had an exhibit in the Soviet Union.

The large-scale installations created in the past two decades with his wife Emilia Kabakov have catapulted them to the forefront of the international art scene. As artists, the Kabakovs move people, critics and viewers alike, because they tell epic and sometimes intimate stories. It is nothing less than poignant that the duo, who are grandparents now, keep reflecting on a Soviet society long gone by. Many of their installations create an echo chamber of emotions as they explore flight, fantasy, memory and the dark side of utopia. Often - but not always - their visions are absurdist or ironic.

“Monument to a Lost Civilization,” now on display at the Moscow gallery Red October was first displayed in 1999 in Palermo. The retrospective includes 37 installations consisting of 140 pieces. “Monument” was also shown at the First Biennale of Contemporary Art in Kiev.

Related :

Ilya Kabakov: The man who flew into space from his apartment

“This has been my principal dream over the past ten years—to set up a monument to the civilization where I was born, where I studied, and where I lived: the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics that no longer exists,” Ilya Kabakov told the curators at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art in Moscow. “I’d like to create an image of that place, not an objective one of course, but the way I saw it and felt it.”

The installation by the Kabakovs is a retrospective of the creative journey of the two conceptualists; it includes solo pieces by Ilya Kabakov, as well as collaborative works with his wife. There are twenty or so display boards, documenting installations by the Kabakovs with sketches, miniature models and photographs.

The 37 installations in “Monument to a Lost Civilization” show the “tension between the real and the ideal,” and the struggle for identity. Each installation is an independent piece of art, an exhibition in itself, formerly displayed elsewhere.

“The Boat of My Life” is a collection of items from Kabakov’s childhood, adolescence and adulthood, arranged in a boat, allowing spectators to walk past and look at the relics, though they hold no personal meaning for them. “The Man Who Flew into Outer Space from his Apartment” is a breathtaking piece. It consists of an empty room with Rembrandt-esque light coming in through a hole in the ceiling, as if a man has rocketed into space from his grim flat.

Another work consists of empty classrooms with posters on the walls. A dark room with collages and pieces of text reflect a son’s relationship with his mother while exploring the woman’s life. In order to make out the writing, the viewer has to use a flashlight, and in doing so, he is able to move along the “beam of memory.”

“The idea was that an entire civilization has vanished, and it needs to be remembered somehow. This was first done as a compressed installation in Palermo, Italy, in 1999, receiving mixed reviews,” Emilia Kabakov said in an interview with Ria Novosti. “We then moved the exhibition to Frankfurt, and later it featured in the ‘Arsenal 2012’ exhibition, part of the First Kiev Biennale of Modern Art. It has now been brought to the Red October gallery in Moscow,” she said.

Ilya Kabakov was unable to come to Moscow to supervise, so he gave instructions via email. “We sent him (Kabakov) all the floor plans of the exhibition space, and he decided which walls and corridors to use, and as far as we could, we made these ideas a reality.” said the exhibition’s curator, Vladimir Ovcharenko, in an interview for the television channel “Culture.”

The artists lead very active lives. They are scheduled to be in Atlantic City (although with the devastation from Hurricane Sandy, this could be delayed). The two will be working on an unusual project to recreate a playground as a pirate’s ship with treasure.

The Kabakovs reach Russia and Europe

The Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, Netherlands, which has one of the largest El Lissitzky collections, will hold a Lissitzky/Kabakov exhibition in December. Lissitzky, a significant figure of the Russian avant garde, was mentored by Malevich. The exhibition will move to the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg and Olga Sviblova’s Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow in 2013.

“The curators at the Van Abbemuseum suggested this idea to us, as they could see a connection between the artists,” Emilia Kabakov told Ria Novosti. “Lissitzky, who was alive during the first half of this century, was full of hope and faith. However, by the end of the century and the end of the Soviet era, Kabakov, who had lived through it all, had lost his faith and become a pessimist. By contrasting the artists’ works, the exhibition creates a link between them,” she said.

The Kabakovs continue to work on a project close to their hearts entitled “The Ship of Tolerance,” which they will bring to Russia in 2013. The ship is always launched from a port—they have launched from Venice, St. Moritz, Manchester, Miami and Sharjah. Local schoolchildren take part in classes discussing tolerance and diversity; then they express their feelings on the topic through drawings that hang on the ship’s mast.

The Kabakovs have held exhibitions in Russia since the early 2000s. In early 2004, the Tretyakov Gallery exhibition “Ilya Kabakov: Ten Characters” from Ilya’s work in the 1970s when he did not formally show his work. Most of his output during that time consisted of collections of drawings up to 100 pages that he used during performances for intimate gatherings at his Sretensky Boulevard attic studio.

In June 2004, the State Hermitage Museum held the exhibition “An Incident in the Museum, and Other Installations,” by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. The exhibition marked the couple’s return to their homeland. At that time, the artists donated two installations to the St. Petersburg museum; according to the director of the museum, Mikhail Piotrovsky, these pieces are the beginning of the museum’s collection of contemporary art.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox