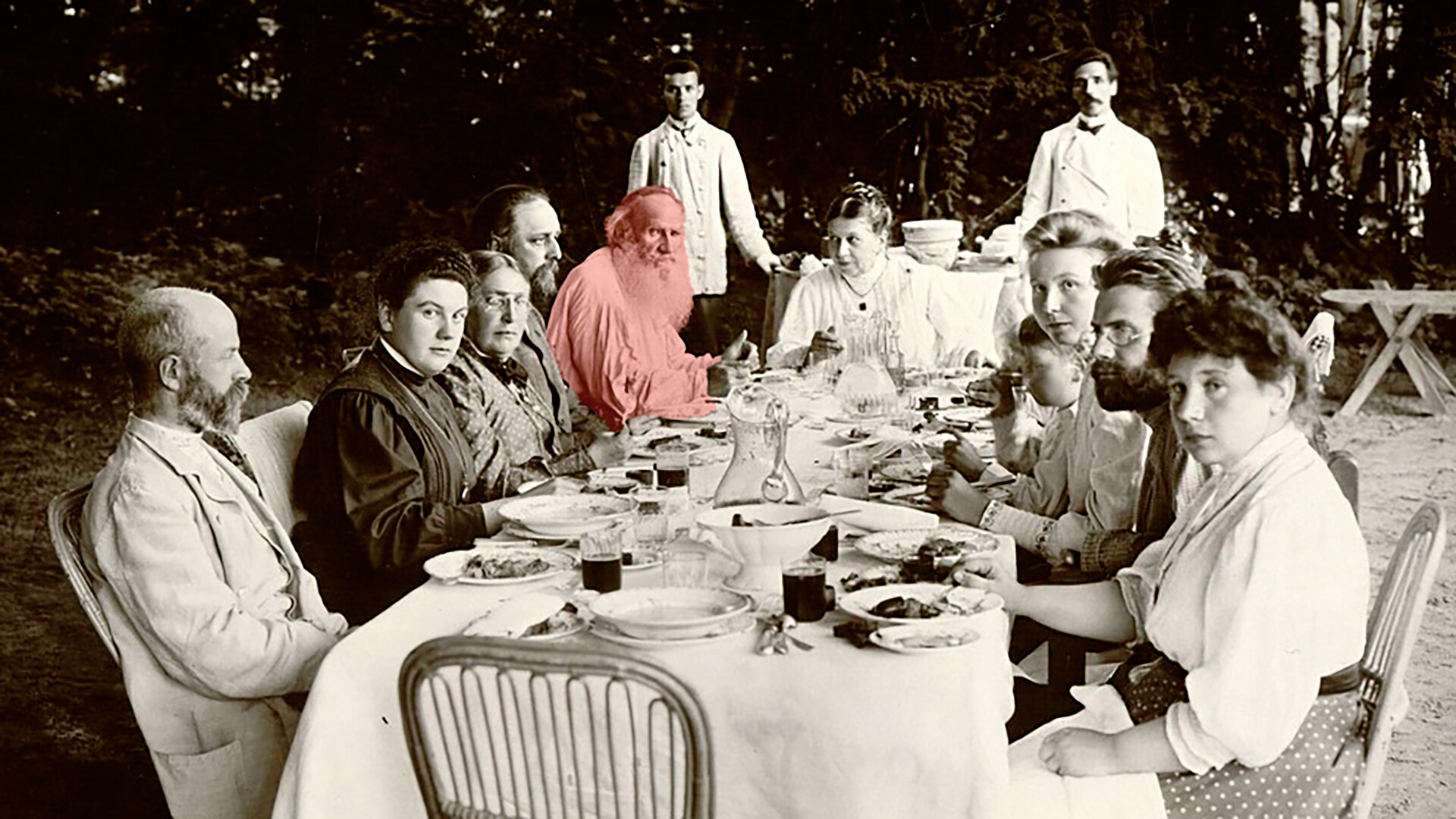

Leo Tolstoy with friends and family taking lunch at Yasnaya Polyana estate. July 7, 1908

Karl Bulla/Leo Tolstoy State Literary MuseumThroughout the 82 years of his life, Leo Tolstoy met and talked to a lot of people. These included other famous writers, imperial court officials, Decembrist rebels (he thought about writing a novel about them but in the end wrote Warand Peace), and simple peasants that he met in his Yasnaya Polyana Estate, where he built a school for children. Many simply wanted to visit and see him, to “touch” this person who was a living legend.

“I often thought that the time will come when all, even the smallest, details of Leo Tolstoy’s life and personality will be studied. And it could so happen that the future reader would need not just information about Tolstoy himself, but about the people in his closest circle as well; particularly, about his friends and acquaintances,” wrote Valentin Bulgakov, Tolstoy’s secretary, who created a series of essays about Tolstoy’s friends and followers.

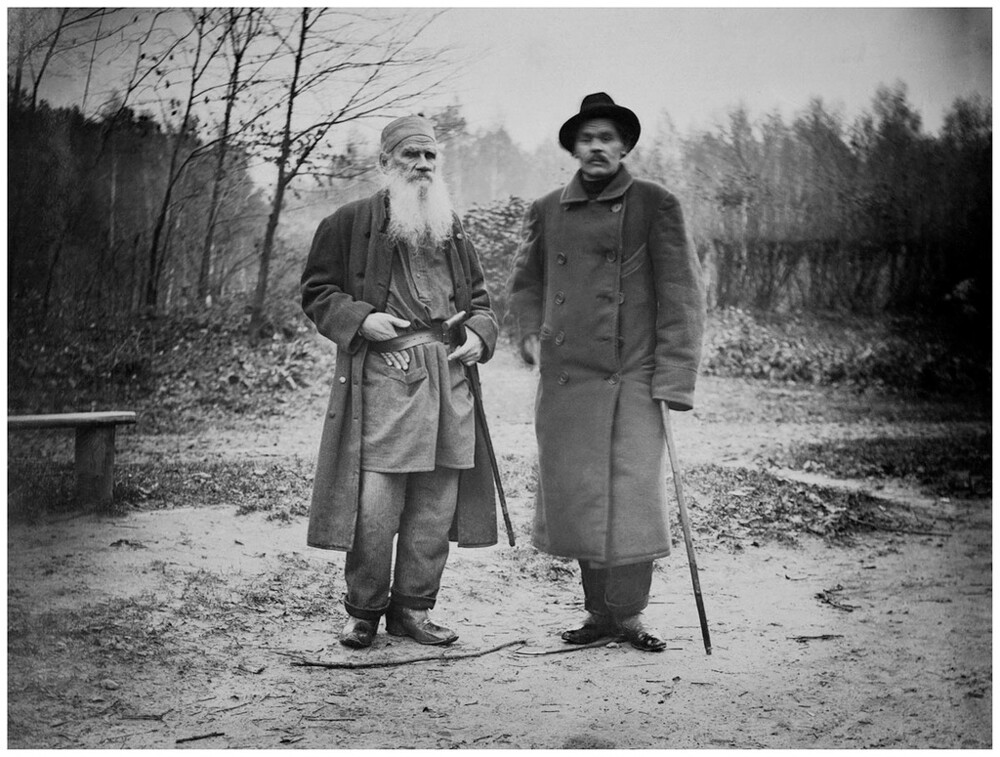

Tolstoy and Gorky in Yasnaya Polyana, 1900

Sofya Tolstaya/Leo Tolstoy State Literary MuseumTolstoy’s relationship with the young Gorky is best explained by the saying “the thinnest line is between love and hate.” At first, Tolstoy was amazed by this “real man from the masses”; and he wrote in his diary, “I like Gorky and Chekhov, especially the former.” Tolstoy was greatly admired by the common folk, and he liked the fact that Gorky showed the bottom of society and lost souls “in all their glory”, “infecting” others with love towards them.

Later, however, Gorky started to irritate Tolstoy. When Gorky first read out loud for Tolstoy some scenes from his play The Lower Depths, which is about life in a homeless shelter, Tolstoy responded, “Why are you writing this?”. He felt that it was one thing to describe such people in episodes, but very much another thing to dedicate an entire work to them. Besides, Tolstoy wasn’t fond of Gorky’s arguments that God doesn’t exist.

The unbelievable success of The Lower Depths was the last straw for Tolstoy. Stanislavsky staged it at the Moscow Art Theater, and it also enjoyed great success in Germany. Later, Gorky toured America, and Tolstoy wrote in his diary that he felt frustrated that the proletarian writer gave interviews to the American press, and that the Russian press also wrote about no other writer except Gorky.

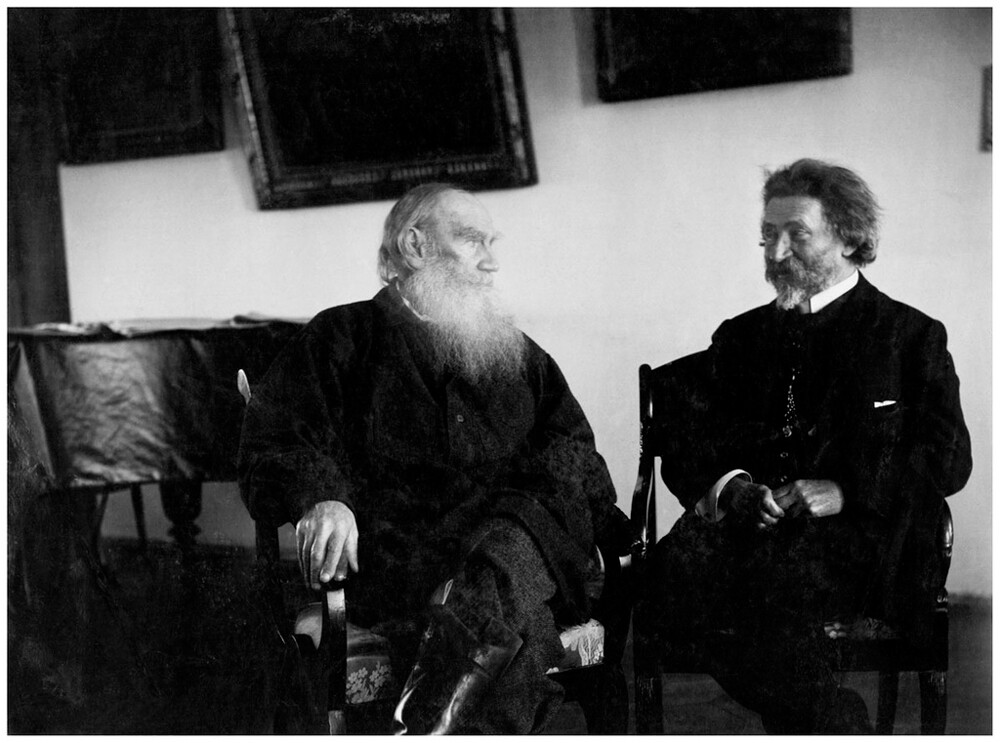

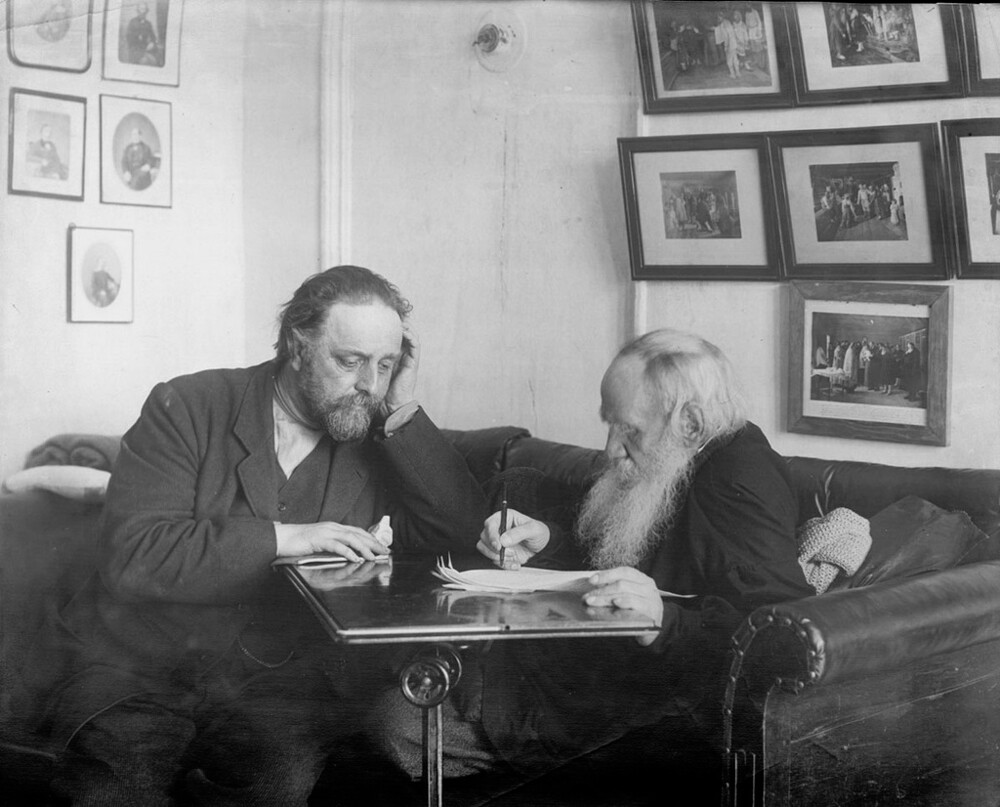

Tolstoy and Repin in Yasnaya Polyana, 1908

Sofya Tolstaya/Leo Tolstoy State Literary MuseumRepin and Tolstoy met in Moscow in 1880. At that moment, Tolstoy was not only a famous writer, he was in a period of “spiritual searching” and rethinking his values. One day he paid a visit to the workshop of this relatively young painter. (Tolstoy was 52, while Repin was 36). Repin remembered that the writer spoke in a deep, soulful voice about how people had grown indifferent to the horrors of life and how they follow the path of depravity.

Repin became a frequent visitor at Tolstoy’s house in Khamovniki; and when the writer visited Moscow, they met for walks and conversations. Their relationship was a friendship spanning many years, and was full of discussions about everything; but often they had irreconcilable differences in the matters of art. Nevertheless, Repin created more than 20 different portraits and sketches of Tolstoy. You can see them in our gallery.

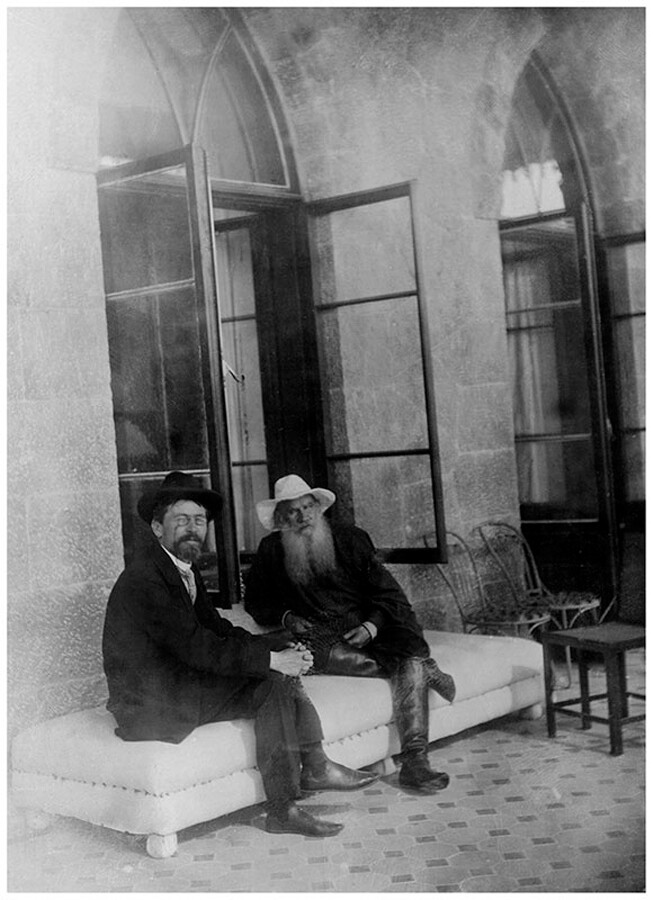

Tolstoy and Chekhov in Crimea, 1901

P.Sergeenko/Leo Tolstoy State Literary MuseumThey met in the early 1890s at Yasnaya Polyana, but even prior to that, having read War and Peace, Chekhov was very interested in Tolstoy and his ideas. A man of many words, Tolstoy enjoyed the short and ascetic short stories of Chekhov. He regarded the short story, The Darling, as a true masterpiece. The main heroine fully loses herself in the activities and affairs of each of her new husbands, adopting their interests and even their manner of speech. By the way, Tolstoy’s daughter, Tatiana, recognized herself in “the darling.”

Tolstoy even lobbied for the publication of new stories by Chekhov when he needed money. We could say that the writers were bound by a tender friendship, and Tolstoy was very worried that his younger friend suffered from tuberculosis. They met in Moscow and in Crimea, where both went for medical treatment. When Chekhov died, Tolstoy was very upset.

While he liked Chekhov’s short stories, Tolstoy couldn’t stand his plays. “I can’t stand Shakespeare, but your plays are even worse.” Tolstoy was irritated by the characters’ inaction. “Where can you go with your characters? From the couch where they rest – to the pantry and back...”

Chekhov himself eventually grew cold toward Tolstoy: “Tolstoy’s morality doesn’t move me anymore,” Chekhov wrote to their mutual acquaintance, the publisher Alexei Suvorin. “War is evil and judgment is evil too, but that doesn’t mean that I have to wear lapti and sleep on a stove along with a worker and his wife.”

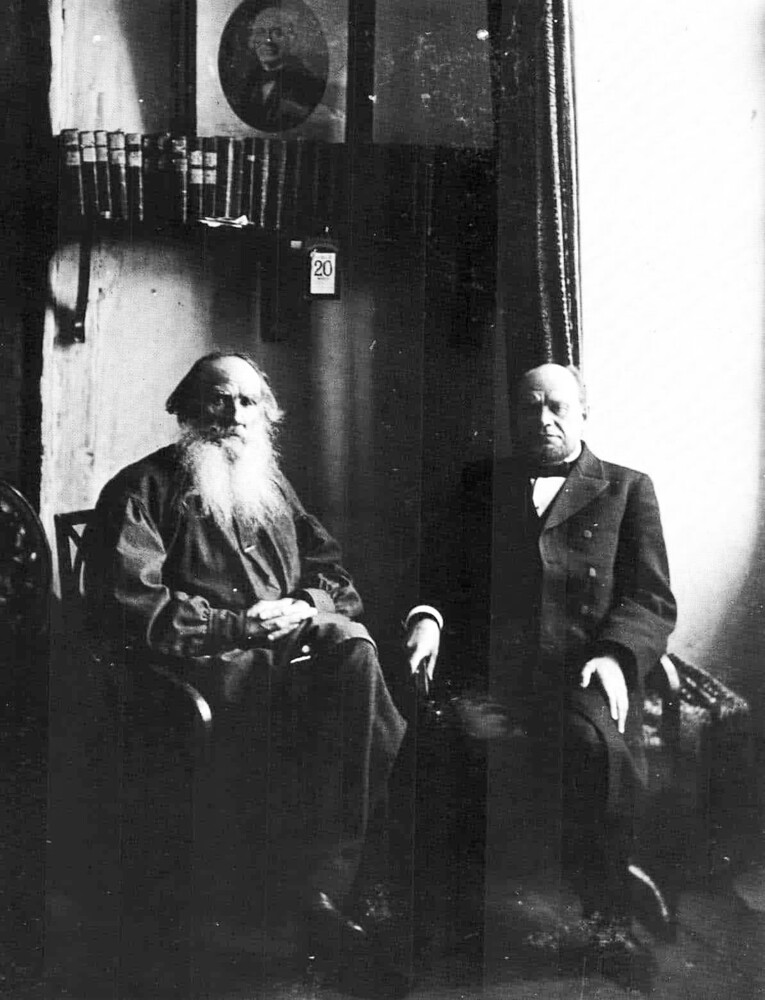

Tolstoy and Koni

Sofya TolstayaThis friendship was especially paradoxical. Tolstoy was nearly an anarchist who criticized any form of authority as violence, and he saw the law as justification for this violence. Anatoly Koni was a leading jurist, a judge, and head of the Criminal Cassation Department of the Senate. In 1887, the Tolstoys invited Koni to visit Yasnaya Polyana.

They later met several times more and corresponded with each other. Once, Koni told Tolstoy about a curious case, how during one trial a juror recognized in the prosecuted prostitute a common woman who he had once seduced and abandoned. His conscience began to bother him, so he decided to help the poor woman, marry her and push for her release. This story shocked Tolstoy and became the foundation of his novel Resurrection, on which he worked more than 10 years and which he considered his greatest work.

Tolstoy and Chertkov in Yasnaya Polyana, 1909

Thomas Tapsell/Leo Tolstoy State Literary MuseumIn the 1880s, Tolstoy experienced a major spiritual upheaval, and his attitude towards many usual and fundamental issues changed dramatically. In particular, he became disillusioned with the Orthodox Church and the institute of marriage as a holy union of a man and a woman. His attitude towards private property changed as well – Tolstoy tried to free himself from riches, began wearing his legendary peasant shirt, and worked the land along with the peasants. Aside from that, he decided to refuse author’s rights for his works, which caused a tumultuous scandal in his family. His wife, Sophia Andreevna, was vehemently against this decision. She understood that this meant the family would be left without funds, and the many children of Tolstoy – without an inheritance.

However, Tolstoy’s faithful personal assistant, Vladimir Chertkov, ardently supported Tolstoy in these impulses. He exercised significant influence over the writer, pushing him to leave his family and move away. Conflicts constantly erupted between Chertkov and Sophia, which tortured Tolstoy.

Chertkov gathered Tolstoy’s aphorisms and assembled his Collection of Thoughts, which the writer himself called “the biography of my thought…” Tolstoy was always happy to receive Chertkov at any moment and even allowed him to edit his texts. Chertkov also published and distributed Tolstoy’s prohibited treatises on faith, for which the author eventually had problems with the police.

Chertkov is also considered the leader of the Tolstoyan movement. For his help to the Dukhobor sect, which embraced Tolstoy’s ideas, the Tsar exiled Chertkov from Russia. Once in England, he continued publishing Tolstoy’s works.

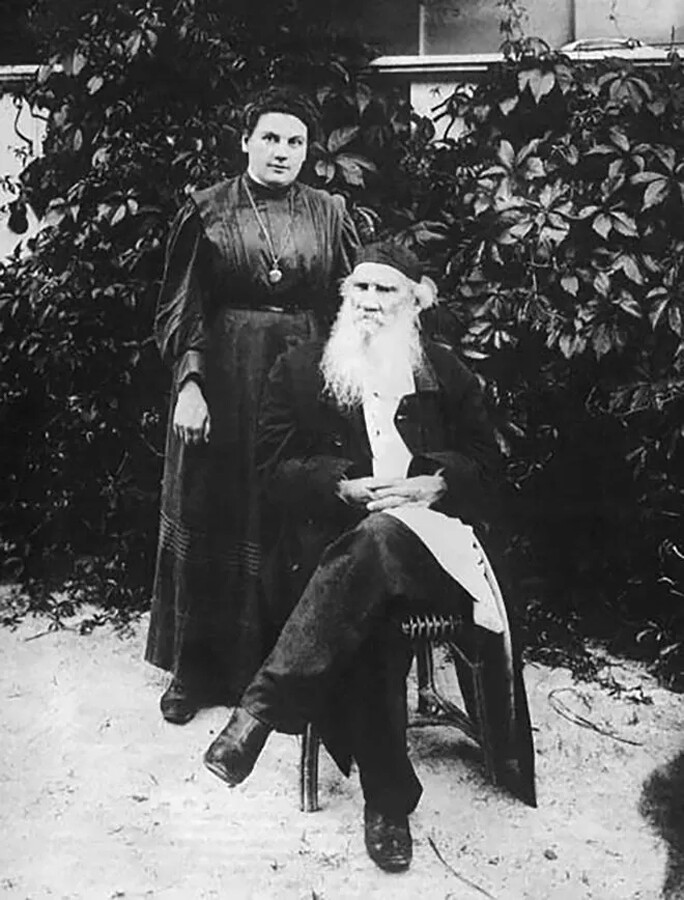

Tolstoy with his daughter Alexandra

Public domainWhile Tolstoy had a complicated and often conflict-ridden relationship with his wife Sophia, his youngest daughter Alexandra was his personal secretary, a true friend, and the closest person to the writer. She dedicated her life to her father’s work and to preserving his heritage.

She founded and became the first head of the museum in Yasnaya Polyana, as well as the Tolstoy Foundation in New York. When the Bolsheviks arrested her for nonconformity, the intercession of the peasants from Yasnaya Polyana saved her from a prison camp. And yet, at the end of the 1920s, she was forced to leave Russia. In 1941, she settled down in the U.S.

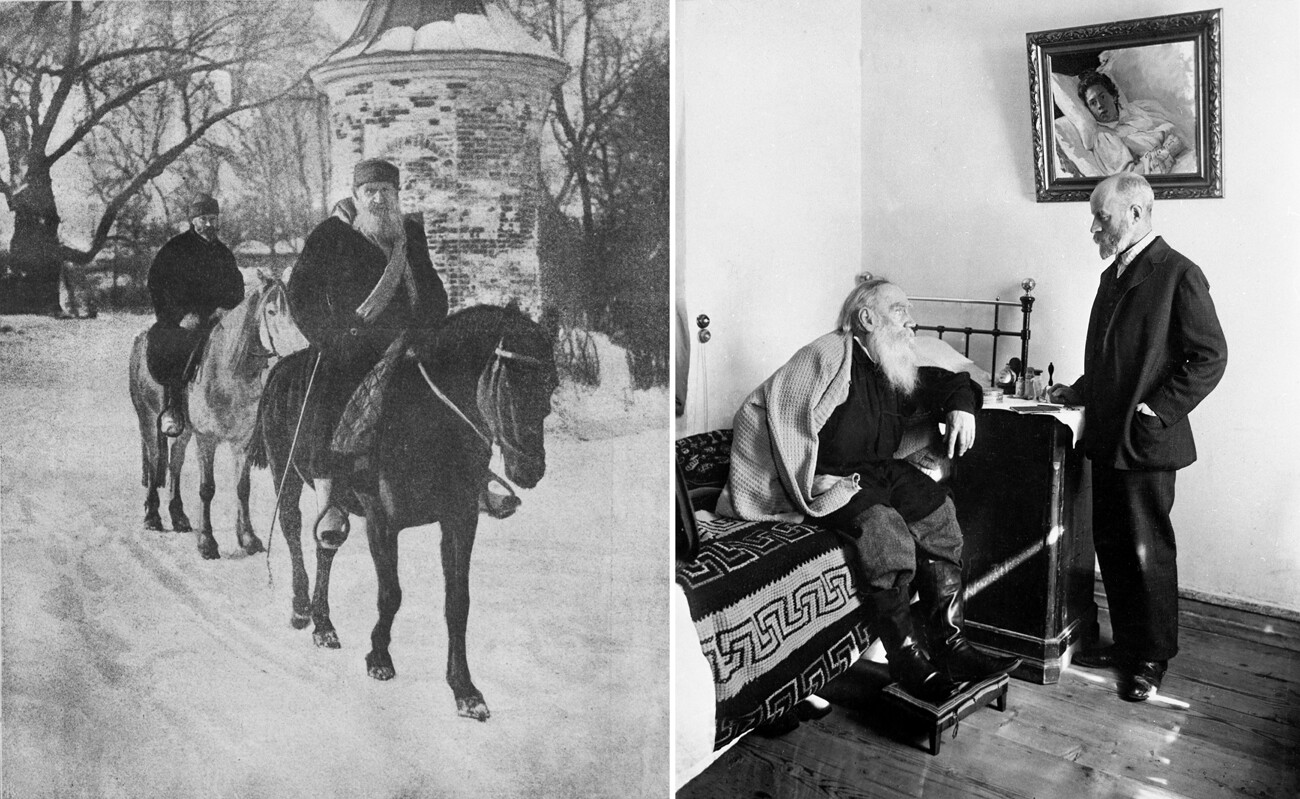

He came from Slovakia and even before he became Tolstoy’s doctor, Dušan Makovický became interested in his views about morality after reading the prohibited novella, The Kreutzer Sonata, which he even translated into the Slovak language. Later, he also translated the novel Resurrection. He also contributed considerably to publishing Tolstoy’s many works overseas. Makovický came to Yasnaya Polyana in 1904, at the invitation of Tolstoy’s wife, to serve as the writer’s personal doctor, but he soon became his loyal friend and an assistant in many things. He also gave medical attention to the local peasants.

Tolstoy liked to have long walks with Dušan and ride horses with him, which he did even at an old age. The writer took this Slovak doctor with him during his secret escape from Yasnaya Polyana, which after several days he died along the way at a train station, with Makovický present. The days he spent with the great writer were reflected in Yasnaya Polyana Notes.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox