Everything you need to know about perestroika in the USSR

Was perestroika a good or bad thing?

In

It is mainly grounded in the hardships connected with the dissolution of the USSR that was one of the results of perestroika. At the same time, almost

Why is Gorbachev often perceived negatively?

Perestroika is

President Mikhail Gorbachev during the second session of the Russian Communist Party congress on Wednesday, Sept. 5, 1990 in Moscow

APThe negative perception of Gorbachev is sometimes explained by Russians’ mentality, alleged people’s traditional hopes for “a kind master” and “a good tsar”. “Having been granted more and more freedom, the people continued to rely not so much on themselves as on a miracle, a “strong hand” and a “decisive leader,” which explains Boris Yeltsin’s rise in popularity,” Pavel Palazhchenko, a person who has been close to Gorbachev for decades, argued.

In his view, the Soviet leader and perestroika are still misunderstood. Russians allegedly misunderstand or consciously reject the main motive of perestroika that was “actively supported at the time by the entire Soviet society - a project of the reunification of Russia with world history and the democratic renewal of the country.”

Other observers, like Gorbachev’s former spokesman Andrei Grachev, underline the idealism behind Gorbachev’s project and point out to the dangers of disillusionment of current Russia that lead to mistrust.

There is also an opinion that perestroika has been misunderstood not only in Russia but also in the West. In Washington, “at best, it was seen as an opportunity to achieve the advancement of U.S. policy interests by taking advantage of the fact that Gorbachev had temporarily disoriented the Soviet leadership,” professor Nikolai N. Petro argued.

At the same time, several years ago some started to notice signs of perestroika in the U.S. and draw parallels between Mikhail Gorbachev and former American president Barak Obama.

Gorbachev’s personal tragedy

Gorbachev admits himself that he has done some mistakes. “Our main mistake was acting too late to reform the Communist Party,” he

Mikhail Gorbachev during the presentation of his new book "Alone with Myself" in 2012

Ramil Sitdikov/SputnikGorbachev shared a lot about his personal life back then in the latest book “Alone with Myself” where he wrote extensively about his wife Raisa, who died in 1999. “I am haunted by a sense of guilt over Raisa’s death. I try to reconstruct it in my memory: Why couldn’t I save her?” the former Soviet leader confessed.

For many

Music that helped destroying the country?

It was the generation that was brought up with different music around than it was the case with their predecessors. Musicians that were underground as a result of the reforms got an access to wider public and became mainstream. These

Western heavy metal rock bands including Bon Jovi, and Cinderella were enthusiastically received by loving fans in Moscow on Saturday, August 12, 1989

APProbably, the most popular singer of perestroika was Viktor Tsoi, a leader of Kino group who is sometimes credited with a role in the USSR dissolution. Russia Beyond has found at least five reasons of his phenomenal popularity that lingers on until now.

Soviet rock musician Viktor Tsoi in Moscow

MAMMPasta and a computer game

Russia Beyond has highlighted other not so well known aspects of perestroika. Here you can read how perestroika affected the popularity of tennis in the country

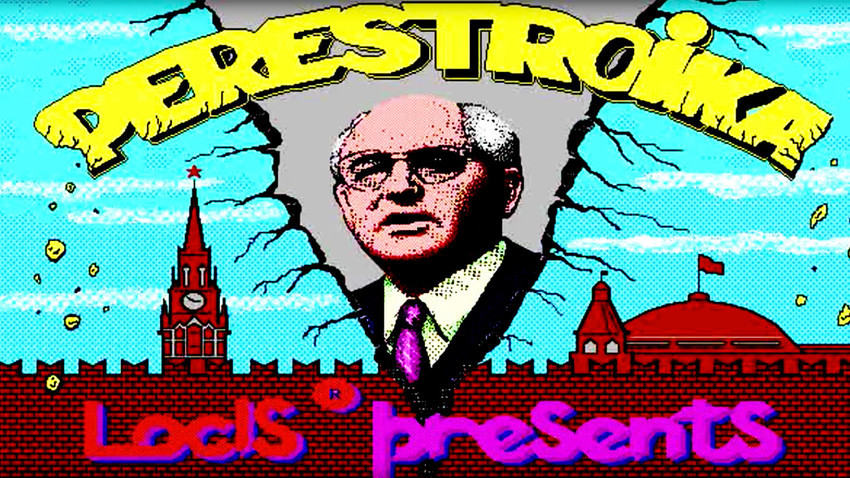

Computer game "Perestroika" enjoyed popularity both in the Soviet Union and abroad

LocisSymbols of perestroika

Although perestroika lasted just for a few years, it had its symbols. By now they have entirely disappeared along with this unique era. But those things are still remembered. These were, among others, the machines for the production of moonshine alcohol,

However, there are things that came from perestroika period and are still with us, such as freedom of speech or

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox