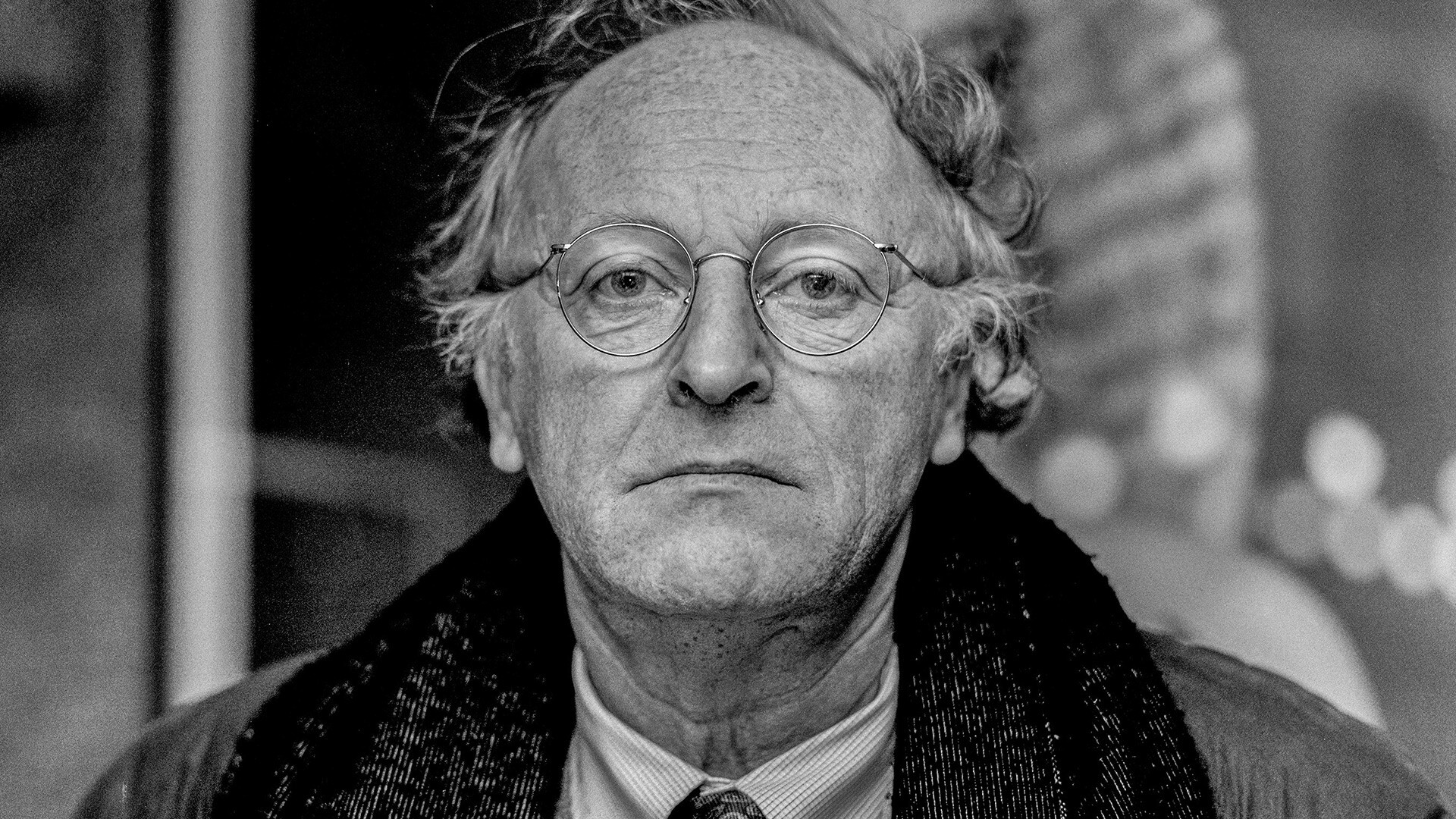

Portrait of Joseph Brodsky made shortly before the death of the poet by Sergey Bermeniev.

Sergey Bermeniev (CC BY-SA 4.0)On June 4th, 1972, Joseph Brodsky left his motherland forever. His departure was forced; in Leningrad, he left his parents, whom he would never see again, as well as the love of his life, his son and his friends.

Under the protection of an American publisher, who adored his works, Brodsky acquired a teaching position at the University of Michigan. Later, in 1977, he received US citizenship, and in 1987 – a Nobel Prize in Literature. Why was Brodsky such a thorn in the side of the Soviet functionaries, who forced him to leave behind everything he loved?

Contrary to expectations, Brodsky wasn’t a fighter against the Soviet regime, a dissident or a Russophobe. Having lived long years in the US, he kept not only his love and respect for his motherland, but also positioned himself as a statist - not as a revolutionary.

Brodsky’s path, according to the opinions of many, was a path of alienation. As Sergei Dovlatov, a famous writer and Brodsky’s friend, wrote, “He was not living in a proletarian state but in a monastery of his own spirit. He didn’t fight against the regime. He didn’t pay it any attention.” Silent resistance wasn’t a principled and conscious position that the poet developed deliberately; for Brodsky, this way of thinking and feeling was organic. He himself remembered that, at the age of 10-11, a thought crossed his mind, which would thoroughly inform the rest of his life path - “Karl Marx’s saying that ‘social existence determines consciousness’ is only correct until one’s consciousness learns the art of alienation; afterwards, consciousness lives on its own and can both regulate or ignore social existence.” For the Soviet system, Brodsky’s consciousness appeared to be too independent.

Joseph Brodsky and Sergey Dovlatov at gallery RR, New-York, 1979.

Nina Alovert/The Pushkin Museum-Reserve «Mikhailovskoye»At the age of 15 Brodsky dropped out of school and went to work in a factory. He would later claim that he just couldn’t stand some of his classmates and teachers, the omnipresent Lenin and Stalin portraits and the obnoxious color scheme used on the walls. The poet was frightened by the fact he encountered this everywhere – not just at school, but any other public place, all depersonalized and meaningless in a uniform manner. The poet would never regret not finishing school and skipping university – it was more important, in his own words, that dropping out of school was the first free choice of his life.

Young Brodsky.

Museum of Joseph Brodsky 'Poltory Komnaty'Brodsky’s inner freedom, so alien to the Soviet system, was reflected in his poetic language: he never criticized Soviet rule in his works, but it felt otherwise. In his conversation with journalist Solomon Volkov, Brodsky explained this phenomenon in the following way: “A poet’s influence stretches beyond his, so to say, time on Earth. A poet alters society indirectly. He alters its language, its diction, he influences the level of the society’s self-awareness. How does that happen? People read the poet and, if his works are finished in an intelligent manner, they begin to settle more and more in the human consciousness.” Brodsky considered the language used by the authorities “soiled by the jargon of Marxist treatises”, “non-Russian” – and from that originated the conflict between the authorities and literature; the former was full of suspicion and prejudice towards the unknown, incomprehensible poetic language.

In 1963, an article appeared in the newspaper Evening Leningrad, titled “Semiliterary Drone”, in which the author subjected Brodsky to harsh criticism: “… his poems are a mix of decadency, modernism and common gibberish”; the author denounced Brodsky for his supposed disdain for his motherland, and for “conceiving a plan of betrayal.” The article ends with a call to punish Brodsky for so-called “parasitism” – then considered a crime.

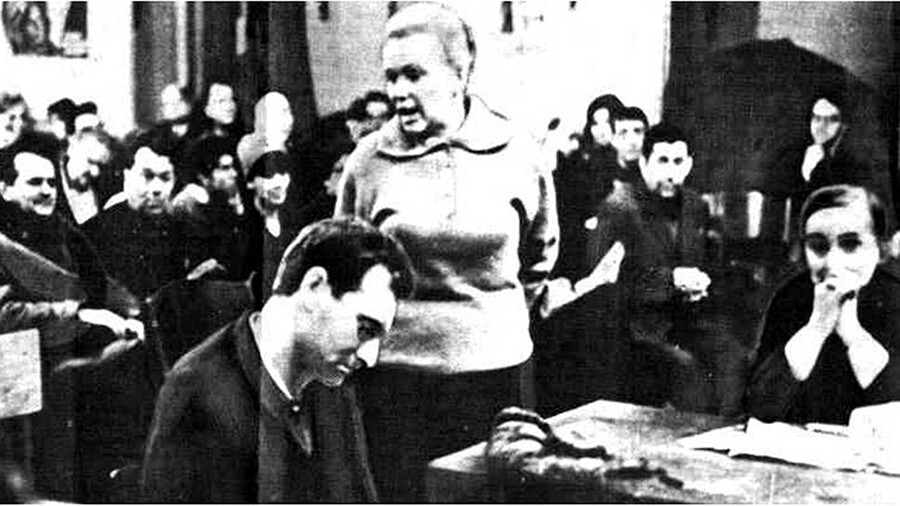

Brodsky's trial.

N.YakimchukThe text of the law explained the notion in very vague terms, leading to its use against any and every person the system had found to be ‘inconvenient’. And the authorities used that opportunity. Brodsky was convicted and spent one and a half years out of five in a labor exile in the village Norenskaya of the Arkhangelsk Region. Thanks to the large public outcry caused by this attempt of the authorities to do something about an inconvenient poet, he was released. Both compatriots and concerned people from abroad supported the poet – by the end of 1964, thanks to French and English publishers, the entire world learned about his trial. However, Brodsky had nowhere to return to. It was almost impossible to incorporate his thinking into the Soviet system. Just as, prior to his arrest, he was translating, writing children’s poems and sometimes getting money for reading poems to circles of interested people.

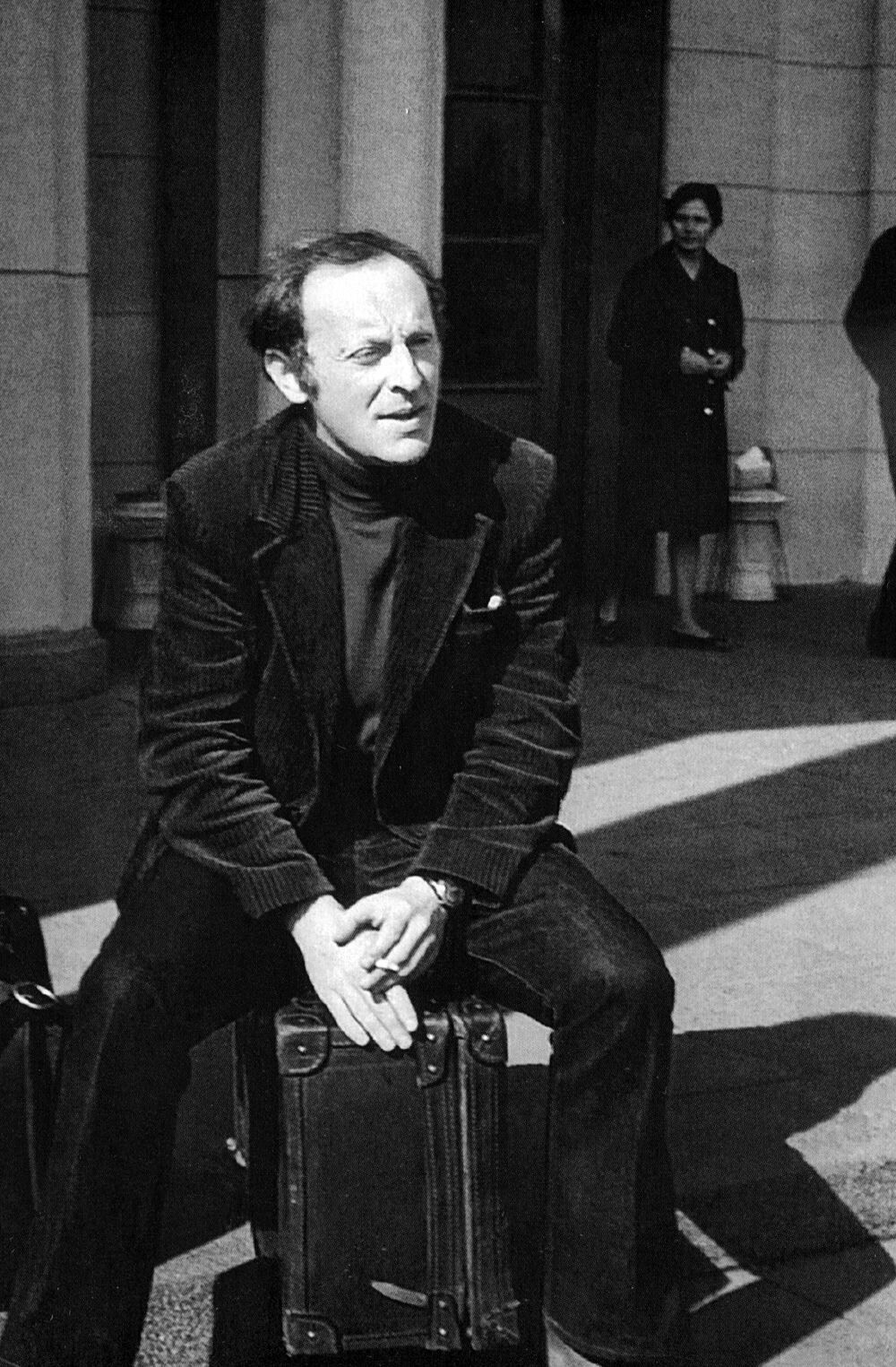

Joseph Brodsky in labour exile in the village Norenskaya of the Arkhangelsk Region, 1965.

Archive photoThe disgraced poet was published overseas – in 1970, his book A Stop in the Desert was published in New York. It contained 70 pieces of poetry and several poems and translations. The trial and the campaign for his protection made Brodsky quite famous overseas, so he began receiving invitations from different countries, among them Israel, Italy, Czechoslovakia and Britain.

As a Jew, Brodsky had the right to repatriation. At the same time, the authorities had absolutely no idea what to do with this strange man: there was nothing to put him in jail for, they couldn’t accept him into the Union or publish his poems. In a strictly systemic country, Brodsky fell through the cracks – he just didn’t fit into the Soviet way of life because he existed on his own, without any external points of support. Such a person was considered by the system as harmful and dangerous. In 1972 Brodsky was invited to the visa department and told directly that it would be better if he accepted the invitation and left. Brodsky wrote about this episode: “From the polite policeman’s formal address he shifts to an informal one. I’ll tell you what, Brodsky. Fill out this form right now, write a statement, and we’ll make a decision. What if I refuse? - I ask. The colonel answers: then you’ll have some hot days ahead.” Brodsky accepted – only three weeks passed from the visa department’s call to the poet’s departure to Vienna.

Pulkovo airport. Brodsky before his departure, 1972.

Mikhail Milchik/Museum of Joseph Brodsky 'Poltory Komnaty'Propaganda portrayed all emigrants as ‘traitors of the motherland’, and it was almost impossible to return after one’s departure. Brodsky left forever and couldn’t even see his parents: 12 times they filed an application with a plea to see their son, but were refused every time. The poet’s parents passed away having never seen him again. After their deaths and the collapse of the Soviet system, Brodsky himself didn’t want to return. “For several reasons I refrain from it,” he wrote. “First: you can’t step twice into the same river. Second: since I have this halo over my head now, I’m afraid I’ll become an object of various hopes and positive feelings. And it’s much harder to be an object of positive feelings than an object of hate. Third: I wouldn’t want to end up in a position of a person with better conditions than the majority.”

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

Subscribe to our Telegram channels: Russia Beyond and The Russian Kitchen

Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter

Enable push notifications on our website

Install a VPN service on your computer and/or phone to have access to our website, even if it is blocked in your country

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox