Since the end of the 15th century, when the Grand Duchy of Moscow appeared as a sovereign state, more and more foreigners began coming to Russia from Europe. They had to be registered with official documents and, most importantly, offered protection. Lacking knowledge of the Russian language, as well as customs, foreigners could easily become prey to thieves. After all, they traveled to Russia on a wide range of commercial business, carrying with them money and valuables. And in the vast and sparsely settled Russian countryside, where one could easily be killed just for a nice pair of pants or boots – foreigners with their fancy clothing and expensive weapons were more likely to become a target for criminals. So the government was directly interested in making sure that foreigners felt safe when traveling inside the country; otherwise, they would stop coming, and their trade and business activity would come to naught.

English merchant of the 16th century

Public domainIt was also profitable to invite foreigners: the taxes levied on European merchants in Russia were three or four times higher than the taxes levied on Russian merchants. In addition, Russians in general were very interested in trade, exchange of scientific knowledge, Western European culture and art.

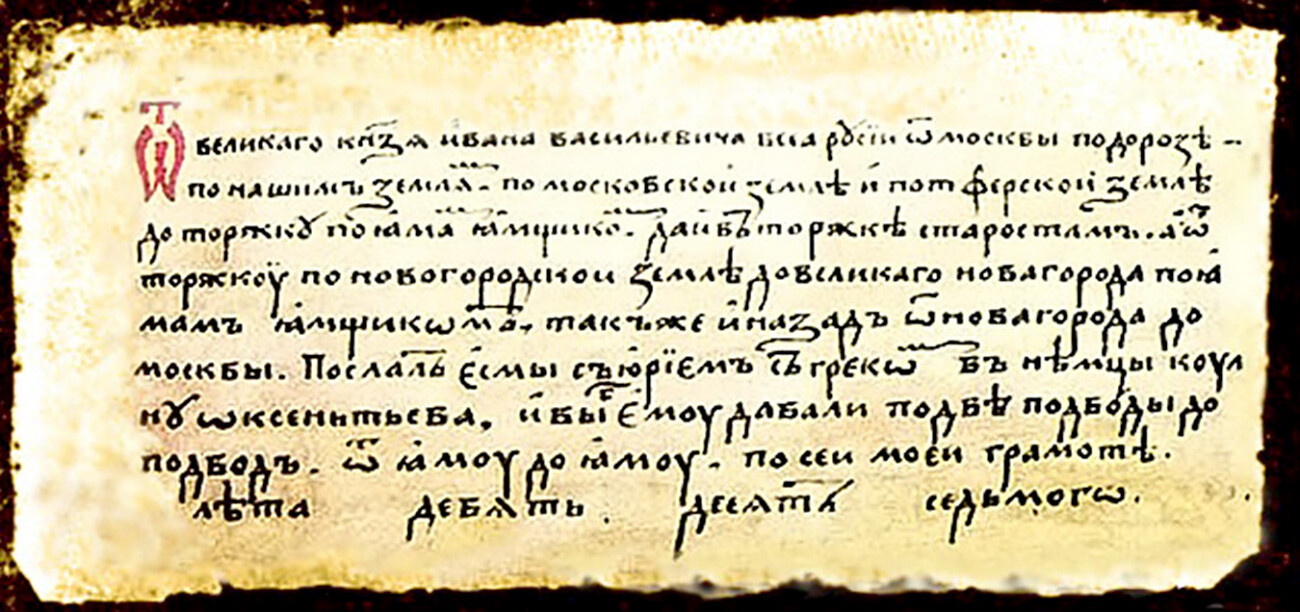

In the 16th-17th centuries, despite the many wars and political crises, military professionals, medics, craftsmen and gunsmiths traveled from Europe to Moscow seeking opportunity. Starting in the 16th century, foreigners entering Russia began to be issued letters of transit with the tsar's official red wax seal. It was necessary to obtain one in the Embassy Office (Posolsky Prikaz), and only after that was it possible to trade or render services.

An example of a Russian charter of transit

Public domainStarting in 1649, the Russian state began to closely monitor its own people: in the Council Code (Sobornoe Ulozhenie) there was a whole chapter "On travel charters to other states". Henceforth, everyone who traveled "for trade or any other business to other states" had to report about it: in cities – to the voevoda (governor), and in Moscow – to the tsar’s office, and receive a charter of transit (proezhaya gramota).

Traveling without a charter of transit was a legal violation, which was subject to a criminal investigation – to determine whether a person was plotting treason. And if treason was uncovered, then the criminal was subject to the death penalty. If it was determined that the person had traveled without malicious intent, then he was whipped – also a severe punishment, after which one could be crippled for the rest of their life.

Count James Daniel Bruce (1669-1735), a Russian general, statesman, diplomat and scientist of Scottish descent, one of the chief associates of Peter the Great

Public domainCharters of transit appeared only in the 16th century. But even before that, it was possible to distinguish between the ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ within the country. First of all, this could be determined by language, as well as by religion. It was common for Russians to consider any Orthodox Christians, whether they were Greeks or from the Balkans, as "their own", on the basis of having a common religion. Most foreigners – Catholics, Lutherans and Protestants — even when living in Russia, wanted to preserve their faith and rituals, so they settled in special quarters (slobodas). In Moscow, there were the Old and the New German Slobodas, where all those who spoke European languages settled. Of course, it was not obligatory to be baptized, but the authorities left these foreigners to protect themselves from Russian xenophobia, as if encouraging them to be baptized.

There was no formal naturalization procedure in pre-Petrine times, but baptism into Orthodoxy served as a substitute. Generally, a person baptized into the Russian faith was allowed to wear Russian dress and leave his foreign sloboda without fear of being beaten. His former name was changed to an Orthodox name (often similar to his former name); he could marry a Russian, and he was gradually assimilated into the population of Muscovite Russia.

Herberstein pictured in a shuba given to him in Moscow

Public domainIn 1702, Peter the Great made it easier for foreigners to enter Russia when he ordered that anyone who joined the army would be supplied with horses and carts to get to their destination – to Moscow, and then starting in 1712, to Saint Petersburg.

In addition, it was also specified "that no obstacles or disturbances were to be caused to the arriving officers in any way, but that, on the contrary, all services should be made readily available to them." They were guaranteed full freedom of religion – it was not obligatory to convert to Orthodoxy to start military service.

Isaac Massa (1586-1643), a Dutch grain trader, traveller and envoy to Russia.

Public domainThe Privy Collegium of the Military Council was established as a special court for foreigners, so that they would not be tried under Russian laws. Peter guaranteed that foreigners would be allowed to leave the service when they wished, and separately mentioned that "merchants and artists intending to enter Russia, have to be received with all possible kindness".

Having defeated Sweden in the Great Northern War, Peter took many foreign prisoners, not all of whom were ready to return home. Therefore, in 1721, for the first time he made it possible to enter Russian citizenship not through baptism, but through a voluntary oath.

In 1747 a single text of the oath was adopted: "I, the below-named, former subject of <some sovereign>, promise and swear to Almighty God that I want to be a faithful, good and obedient slave to His Highness tsar <name of the Russian Tsar> and to be his subject under my own name forever, and not to go anywhere abroad and not to enter foreign service". It remained like that during the entire 18th century.

Taking an oath in the Russian Imperial Army

Public domainEmperor Paul I removed the word "slave" from the text of the oath, but at the same time ordered that there be supervision of all foreigners. Starting in 1807, foreigners who did not become the emperor’s subjects were forbidden membership in Russian merchant guilds - that is, they could not become wealthy businessmen. It was only possible to trade, work and render services.

Starting in 1826, Emperor Nicholas I simplified the acquisition of citizenship – the oath could now be taken in the provincial board at the place of residence, and it was not necessary to go to the capital. However, for a long time, until 1864, naturalized foreigners were not equalized in rights with subjects "by birth".

In addition to foreigners, Russia had many indigenous inhabitants who were called inorodtsy because of their different ethnicity – these were Bashkirs, Kirghiz, Kalmyks, Samoyeds, Buryats, Yakuts, Chukchis and others.

Russia tried to Christianize these peoples, but it was not successful – some were baptized into the Orthodox faith, but most of them retained their own native faith and traditions. Therefore, the government decided to let them maintain their original clan government and common law. They were also granted exemption from certain fees, military conscription, certain types of criminal punishment, and so on – everything was done to keep them loyal subjects and not to provoke religious and ethnic conflicts.

At the same time, foreigners such as Tatars, Chuvash, Mari, Mordva, Udmurts, Izhorians, Karelians, and Veps who lived in the central and western part of the Russian lands were obliged to pay taxes and fulfill their other duties before the state. From Petrine times, their settlements were included into the general system of administration. With time, Orthodoxy spread widely among them.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox