What's behind the West's stereotyping of Russian women?

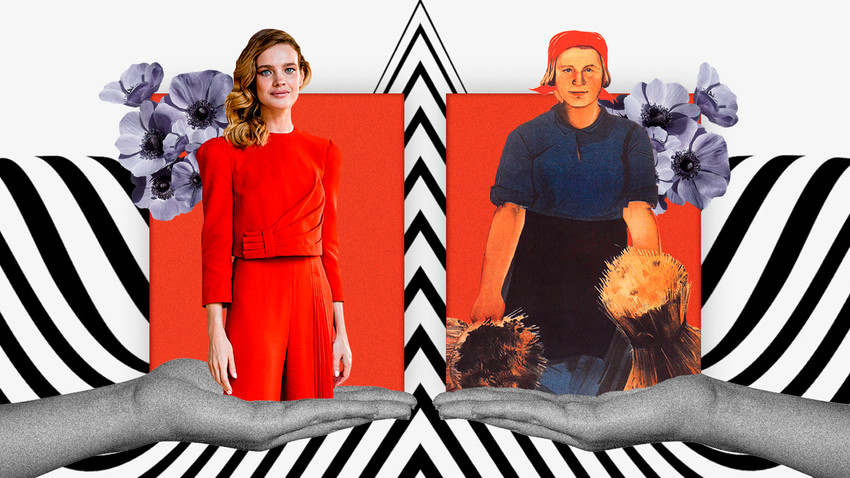

What are the first images that come to mind when you think of a Russian woman in 2019? You’d be forgiven for thinking of a tall femme-fatale who religiously watches her diet and eats men’s hearts for breakfast. We have the new Cold War to thank for that. The KGB honeytrap look is back in vogue, to say nothing of the classy look we ourselves propagate. Plenty of surveys conducted over the past 10 years suggest that we favor tall, slim women of unreal beauty like model Natalia Vodianova or pop singer Vera Brezhneva.

If you’re still in doubt, here’s our number one techno music export, Nina Kraviz, who’s made a global name for herself while shrugging off sexism and misogyny. Today, it’s hard to be a pretty Russian without attracting the opinion that you’re simply given things for your looks.

However, in the Soviet Union’s heyday, Russians themselves had no qualms about depicting their women as something resembling a combine harvester - tirelessly and efficiently collecting wheat, always ready to “work and defend” the country (cue music from the Terminator movies).

Does it mean that up until the 1980s period of Glasnost (‘Openness’), our women all looked like masculine tractor-driving types? Not really. People argue over this all the time: the image of a ‘babushka’ (grandmother) with moles, bushy eyebrows and a husky voice is often brought up to indicate what the West used to think of us. On the one hand, it’s on point: Americans still poke fun at their own cartoonish stereotyping of us through popular culture, especially the cartoons.

But let’s get real: there are beauty standards and then there are cultural perceptions. The latter dimension is completely distinct, and tends to color people’s perceptions of the former in humorous and very misleading ways. For one, it’s anachronistic: it obeys not the trends of the times, but the perception that is most easily marketed to the viewer.

One of the funniest caricatures we’ve seen in modern times has to be the character of Fran Stalinovskovichdavidovitchsky (yes, that’s her name) from the Ben Stiller/Vince Vaughn comedy, Dodgeball (2004), portrayed by Missi Pile, who looks nothing like that in real life. Observe the big mole and the musculature - a dead giveaway that she’s based on a “Russian”. She even works for a nuclear power plant!

Younger audiences believe that the West has always insisted on depicting our women as fat old hags or farm workhorses, capable of taking on a bear in a fist fight. But the Russians were only too happy to oblige - we relied on that image ourselves. Quite often, another’s cultural stereotypes might just be bastardized versions of how you perceive yourself. We were very monolithic in our portrayal of women in Stalin-era Soviet Union, all the way through to the 1970s.

But then, painters like Kustodiev had always shown that modern Russian beauty stood on the shoulders of hundreds of years of obesity and heft and was meant to symbolize wealth in a feudal country that practices slavery. The wealthy looked plump and with a nice peachy glow, while the poor, on top of that, also sported masculine features... just look at the Worker and Kolkhoz Woman statue in Moscow: you can’t tell who the woman is until you see the skirt!

And even that is just one angle. Throughout the 19th century, and up until the Russian Revolution of 1917, Russian women were depicted as Turgenev’s characters (a phrase so often used it is now a literary expression), or a pale Sonia Marmeladova from Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, or the frail Natasha Rostova from Tolstoy’s War and Peace. So, it depended on what period you looked at, or which audience you wanted to speak to. The Soviets then took that, and smothered it with the whole traktor-driving image, subsuming the enigmatic beauty of a Russian woman as a distinct and delicate being under the masculine ideology of collectivism. Note here - it’s not about which gender ruled over another, but rather about Soviet bolshevism requiring masculine characteristics in order to seem steadfast and convincing. Men are physically larger, and women needed to be portrayed as… well - scary.

Some say that the whole image of Russian women as tractor combines had ended with the Cold War simmering down. That is to say - they think that Hollywood and the West at large had only stopped making fun of us when we warmed to Americanization and market economics. There’s no truth to that. Long before the Cold War had ended, Americans and Brits had already been doing us huge favors with their depictions of sexy Soviet field operatives and nuclear scientists: look at literally every James Bond movie of the last 60 years involving a Soviet person. (Spasibo, guys!)

In truth, much of what you’ve seen on the silver screen for the past 100 years is the truth. “So what is the sin then?”, you may ask.

Well, the sin - if you can call it that - is that it often comes out as anachronistic by design, and frequently for a political reason. Take Red Sparrow (2018), starring Jennifer Lawrence, who plays a frail ballerina forced to become a KGB sex spy in order to lure bad guys out of hiding: one would think that this sort of over-the-top depiction of a place that’s cold and unwelcoming to women would be behind us. But Hollywood still needs to rely on frail Russian women in order to depict the horrible place they’re escaping and, in the end, overcoming. Until Russia stops being enemy no.1 for the United States (and therefore, Hollywood), these exaggerations will continue to take place. Whether our women are slim or obese, jovial or morose - it doesn’t matter, because it’s all true in some way.

Another case in point is Anna (2019), which just hit theaters in the United States. Surprise, surprise - it revolves around another KGB honeytrap who spends most of her youth being slapped around by men and - fast forward five years later - takes 20 men in hand-to-hand combat in a restaurant in 1990s Moscow.

Oksana Bulgakowa, in her article "Russian Vogue" in Europe and Hollywood: The Transformation of Russian Stereotypes through the 1920s, refers to German-American film director Ernst Lubitsch for an explanation. After releasing his 1928 film, The Patriot, Lubitsch confessed: “We can only show Russia in a ‘style-Russe’, because otherwise, it would appear unconvincing and atypical. If we show Petersburg as it is, the non-Russian public would not believe us and say: “That is not Russia, but France.”... We are not historians or biographers, we are dealing with the imagination and feelings of the audience.”

What’s more, according to the author, Russian directors exiled from the Soviet Union used to follow the same logic. And it was very different from the conscientious Russian emigres. Unlike the latter group, those who were exiled didn’t care about their portrayals being true to form, nor about building bridges between immigrants abroad. They were salesmen.

A little later on, around the time of World War II, we began to see something completely different - an era of tentative Russian-American friendship, wherein the world was forced to work together against Nazi Germany. Historians are split on whether this period should be observed within the milieu of the later period of Cold War confrontation - as a sort of preamble to later portrayals of Soviets in Hollywood - or rather, be seen in its own right. In either case, Raisa Sidenova, in her essay Mother Russia and her Daughters: Representations of Soviet Women in Hollywood Film, 1941-1945, believes the period deserves special attention.

Remember how we mentioned that the Soviet image of the woman was, to the Russians themselves, slanted toward something rough and masculine? In this exact light, femininity played a crucial role in reversing that during the wartime cooperation between Americans and Soviets.

“The feminization of the Russian image,” as Sidenova calls it, was recognized as a propaganda tool by Roosevelt's administration. “These films revisited the previous, often rough and masculinized cinematic portrayals of Russia and the Russian people and offered a more friendly and feminized image, that showed audiences the necessity of collaboration with the Communist state, as well as the Soviets' trustworthiness and reliability.” She mentions films such as Mission to Moscow (1943), The North Star (1943), Song of Russia (1944) and Days of Glory (1944), all of which “feature portrayals of benevolent Russians and reflect the shift in America’s perception of Russian female character from masculine and aggressive to feminine and needing protection.”

However, while you can see with the naked eye that Red Sparrow or Anna (or even Agent Natalya Romanoff from Marvel’s Avengers series) use the same visual trickery, the latter examples are depicting Russian women as frail, but deadly. This, of course, is crucial for the world we inhabit today, as though they’re telling the viewer to beware of Russia charming its way into your good graces: it’ll slit your throat once your back is turned.

Before we’re done here, let us leave you with our list of the sexiest Russians to ever grace the silver screen. Unlike the Hollywood stereotypes, these are actual Russians, and they perfectly get across our own views of what a perfect woman was seen as in the eyes of 20th century Russians. Their work in cinema has immortalized them, and our opinion of their looks is unlikely to ever change.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox