In 1962, the last tenant left the Moscow Kremlin and there have been no residential apartments there ever since. But once, the entire kremlin was densely populated: it used to be home to tsars, patriarchs and boyars. Later, tsars were replaced by emperors and general secretaries, while boyars - by courtiers and party grandees.

The first fortifications, which appeared on the site of the modern-day Moscow Kremlin in 1156, were built around the prince’s court and courtiers’ houses. The first settlements were located near the Borovitsky Gate. Usually, the prince’s court looked like some separate constructions which were all together called “mansions” and almost each member of the princely family had their own room. The wooden constructions began to be replaced by stone ones in the 14th century, after the white-stone kremlin was built under Moscow Prince Dmitry Donskoy.

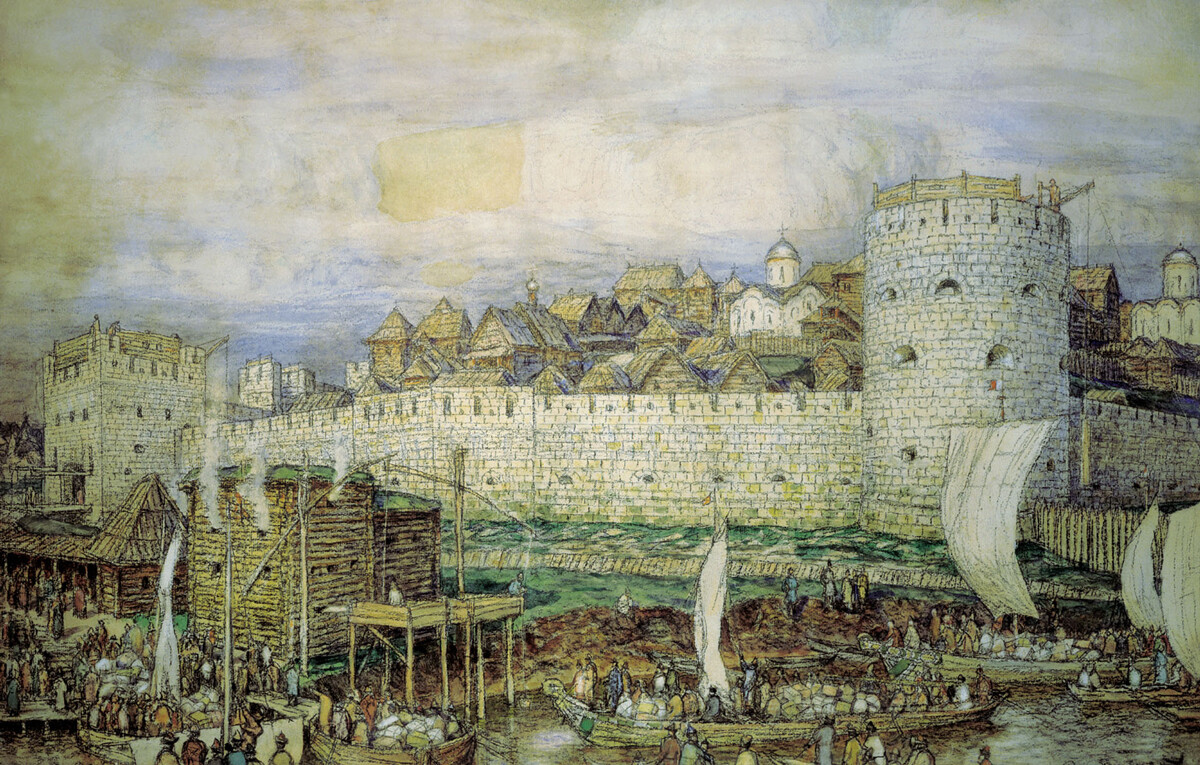

What Dmitry Donskoy's Kremlin supposedly looked like.

Public DomainThe princely court began to turn into a truly luxury residence with the start of the radical reconstruction of the Moscow Kremlin on the initiative of Ivan III in 1482. With the marriage of the Russian tsar to Sophia Palaiologina, the successor of the last Byzantine emperor, Moscow inherited the traditions, status and state symbols of Byzantium. The marriage and Moscow’s new role obliged it to have a dignified residence erected. Ivan III rebuilt the fortress itself and constructed several churches. Wooden residential houses were gradually replaced by stone buildings - first, it was done by the boyars and, later, the construction of the first stone palace was started by Ivan III.

The first stone palace has not survived, but a part, the so-called “princess's half”, became the basis of the Terem Palace, which is, to this day, the hallmark of the architectural ensemble of the Moscow Kremlin. The Terem Palace, built for Mikhail Fyodorovich, the first tsar of the Romanov family, was the first stone residence of the royal family and was designed like wooden chambers. The Terem Palace remained the tsarist residence until the rule of Peter I.

Terem Palace and its interior.

Kremlin.ru; Иван Шагин/МАММ / МДФ/Russia in photoApart from the rulers and their families, the high clergy and boyars lived in the Moscow Kremlin. In 1653-1655, on the order of Patriarch Nikon, Patriarchal chambers were built there, where Nikon lived and received visitors: they have survived up to this day. Also, on the territory of the kremlin, houses for the noble boyars were built, with the Poteshny palace becoming the most famous among the extant boyar mansions. It was constructed for boyar Ilya Miloslavsky, father-in-law of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich.

Amusement Palace.

A.Savin, WikiCommonsLater, members of the royal family, such as Empress Elizaveta Petrovna lived or temporarily stayed there. But most of the buildings were handed over to the “collegia” (ministries) and, soon, the kremlin became an extremely uncomfortable place to live in. The collegia moved in there with all the officials, archives and guards. In 1727, the authorities of the Treasury Court, which kept the tsar’s treasures, wrote:

“…Any rubbish from the tenants and from the horses and from the convicts, which are kept at the expense of the Oberbergamt, puts the tsar’s Treasury in quite a lot of danger, because that results in a stink and this may cause a serious harm to His Imperial Majesty’s gold and silverware and other treasures, causing them to blacken…”

On top of it, the Moscow Kremlin lost its status of the official residence, because of the transfer of the capital to St. Petersburg in 1712 at the will of Peter the Great. The city built by the tsar was closer to Europe and had access to the sea, by which foreign visitors could get to Russia more safely and easier than by the overland road to Moscow.

The last inhabited building on the territory of the kremlin was the Grand Kremlin Palace. Its construction was started on the order of Nicholas I in 1837 and was completed in 1849. It is still the main residence of the President of the Russian Federation, although he actually lives in Novo-Ogaryovo, Moscow Region.

Grand Kremlin Palace.

Pegushev (CC BY-SA 3.0)After the transfer of the capital, the kremlin served as home for the royal family only during their rare visits to Moscow, most often during coronation ceremonies. For the rest of the time, it was the Kremlin Commandant and his chancellery, officials with their families, monks of the monasteries located within the fortress and servants who resided there.

In March 1918, the Bolshevik government again moved the capital to Moscow. This followed a covert relocation of the party’s top brass: the Bolsheviks were initially housed in the capital’s hotels and, later, they moved into the kremlin. Lenin personally approved the place as the seat of the new government. The residential buildings were specially equipped for the new tenants: “In the Cavalier building, opposite the Poteshny Palace, the kremlin officials lived before the revolution. The entire lower floor was occupied by the high commandant. His apartment was now divided into several parts. Lenin and I were lodged across the corridor from each other. The dining room was shared. […] The music clock on the Spasskaya Tower was rebuilt. Now, the old bells, instead of ‘God Save the Tsar’, were slowly and rhythmically ringing out ‘Internationale’ every quarter of an hour,” wrote Leon Trotsky. By Midsummer of 1918, more than 1,100 people lived in the kremlin and, by the end of 1920, the number of people reached 2,100. Officials (now Soviet) used apartments in the kremlin for free. The apartments usually comprised an office, a dining room, a library and one bedroom for each family member. Nami Mikoyan, the wife of Politburo member Anastas Mikoyan, recalled living in the Moscow Kremlin as follows:

“The old marble stairs were covered with a red carpet with yellow flowers along its edges. Such ‘kremlin’ walkways could only be seen in government buildings… Life in the kremlin seemed to be closed off from everything. We lived there like on an island, but the island was not exotically luxurious, but rather a comfortable silent prison, fenced off by a red-brick fortress wall.”

Lenin's apartment in Kremlin.

Иван Шагин/МАММ / МДФ/Russia in photoIn part, the Moscow Kremlin was used as a dwelling, due to the shortage of housing in Moscow, but the question of security was just as important:

“The kremlin was completely deserted. Guards stood at the entrance to the arch of the Borovitsky Gate (near the Stone Bridge)… Only members of the Politburo could drive into the kremlin without stopping. If family members, even those who lived there, were riding, the driver would stop on the right side near the arch, the guards would check the documents, call the senior officer on duty and the car, after the green light was given and the call was made, would be let through […] Family members who lived in the kremlin had special passes - small dark cherry-colored booklets with a photo, full name, on stamped paper, signed by the Kremlin’ commandant. Their covers featured the embossed letters ‘Kremlin’. The guards knew everyone by sight and by name…” wrote Nami Mikoyan. Up until 1955, the Moscow Kremlin museums were closed for excursion groups.

In 1931, the construction of the famous House on the Embankment, built for the employees of the top government bodies, was finalized. Quite soon, a significant part of the Moscow Kremlin tenants moved there. The eviction process lasted for years, though, and the last resident, Kliment Voroshilov, one of the first Soviet Marshals, left the kremlin in 1962.

The house on the Embankment.

Ludvig14 (CC BY-SA 4.0)Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox