On the streets of downtown Moscow, Fyodor Schechtel’s buildings easily catch one’s eye. Eclectic mansions encompass Neo-Gothic, Art Nouveau and Neo-Russian styles. Below, we detail the most famous buildings.

By the time Schechtel had received an order from Matvei Kuznetsov, the owner of several porcelain factories, he had already managed to prove himself as a talented architect. He participated in the competition for the Historical Museum on the Red Square (although a different, similar project was eventually chosen) and designed the facade of the Paradis Theater (present-day Mayakovsky Theater).

The building of Paradis Theatre, 1890.

K.А. Fisher /Public domain/Legion MediaIn 1893, the Kuznetsovs decided to rebuild the southern wings of their mansion. As a result of Schechtel’s work, the two outhouses were merged into one mansion with a bay window and minimal décor.

The Kuznetsovs’ city mansion.

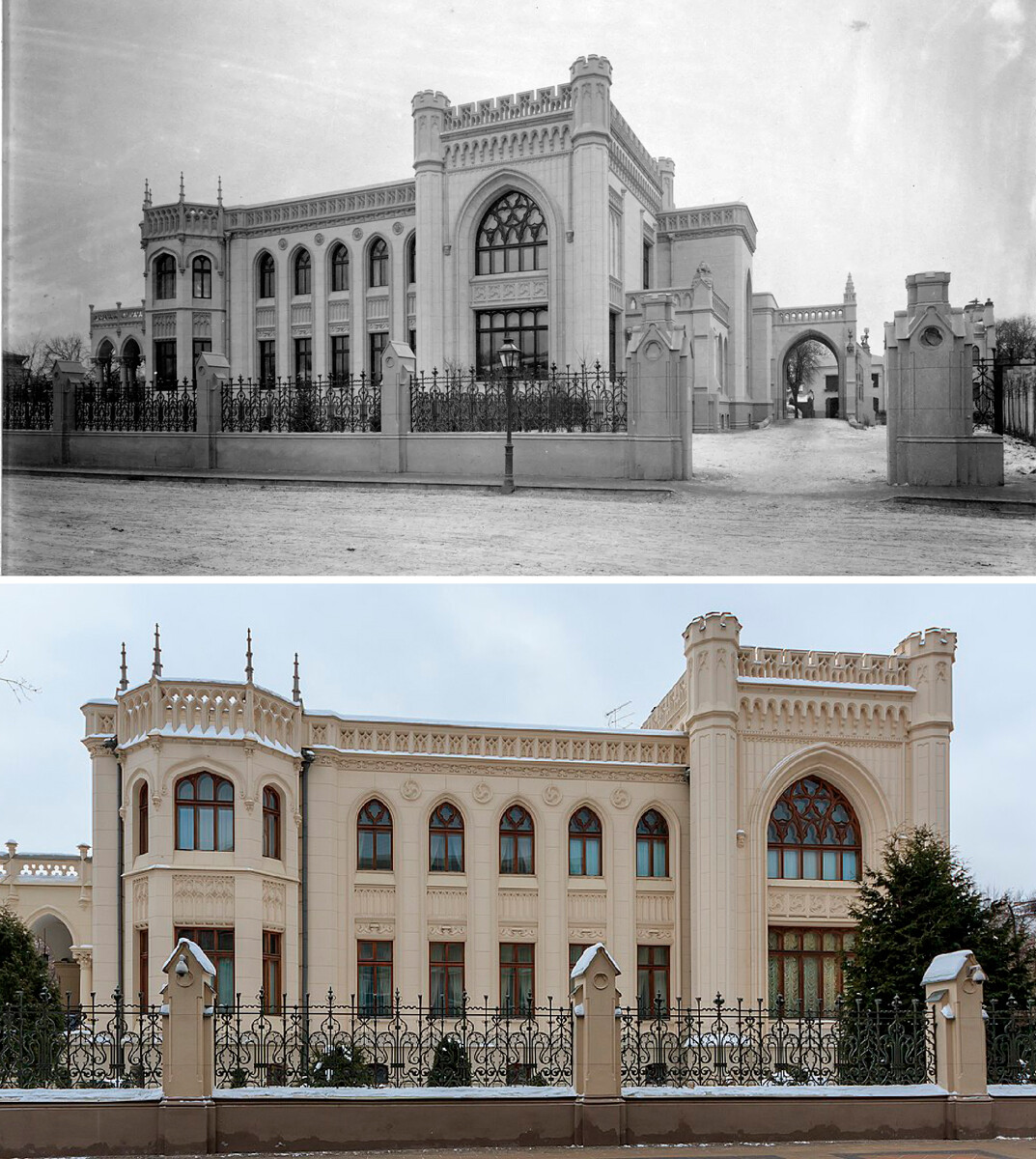

Polezhaev / Schusev State museum of architecture / pastvu; pastvuA year later, the architect proceeded to the second order of the Kuznetsovs. A Gothic style house was built next to the mansion according to his design. It had arched windows, decorative towers and the central window of the facade was made in the English Temple Gothic style. Both the mansion and the house are located at the same address, but while the former is regularly restored and looks close to the original, one wouldn’t recognize the Gothic mansion at all. In the 1930s, two floors were added to the house and it was completely covered with a new facade, so none of the original details are currently visible.

Kuznetsova's mansion before and after the reconstruction.

Public Domain; Apr1 (CC BY-SA 4.0)Industrialist Savva Morozov, one of the richest merchants of the Russian Empire, ordered this house as a gift to his wife Zinaida. From the designs presented by Schechtel, he chose a mansion in the English Neo-Gothic style. Savva Morozov was a famous Anglophile. In two months, Schechtel created about 600 drawings - not only of the exterior of the building, but also of the entire interior, down to the door handles and wallpaper patterns.

Zinaida Morozova’s Mansion in 1898 and now.

pastvu; A.Savin, WikiCommonsThe interior of the mansion is just as remarkable as its exterior. Upon walking through the doorway, visitors find themself in a Gothic vestibule with vaulted arches, a coffered ceiling and blue wallpaper depicting boxes of cotton, which from afar resemble royal lilies (an allusion to Morozov’s textile manufacturer).

The hall of Zinaida Morozova's mansion in the end of XIX century.

Public domainThe decorations are mostly made of dark oak; stained glass windows, varying in shape and size, have been inserted. The central fireplace depicts two knights with shields and in armor.

The dining room in Zinaida Morozova's mansion.

I.Palmin / Public DomainThe construction of this mansion was a turning point in Schechtel’s career. The innovative techniques used in its construction were the final touches on the way to forming the architect’s distinctive style. The house was located in the middle of the land property, although, at the beginning of the 20th century, it was common to bring the facade as close to the street as possible. All details were enlarged on purpose and the height of the ceilings was increased. This created an effect of monumentality. Thanks to this building, Schechtel received the right to conduct construction projects on his own. Since he did not have an architect’s diploma, he submitted the drawings of the mansion as an examination paper. After this project, Schechtel shot to fame and popularity.

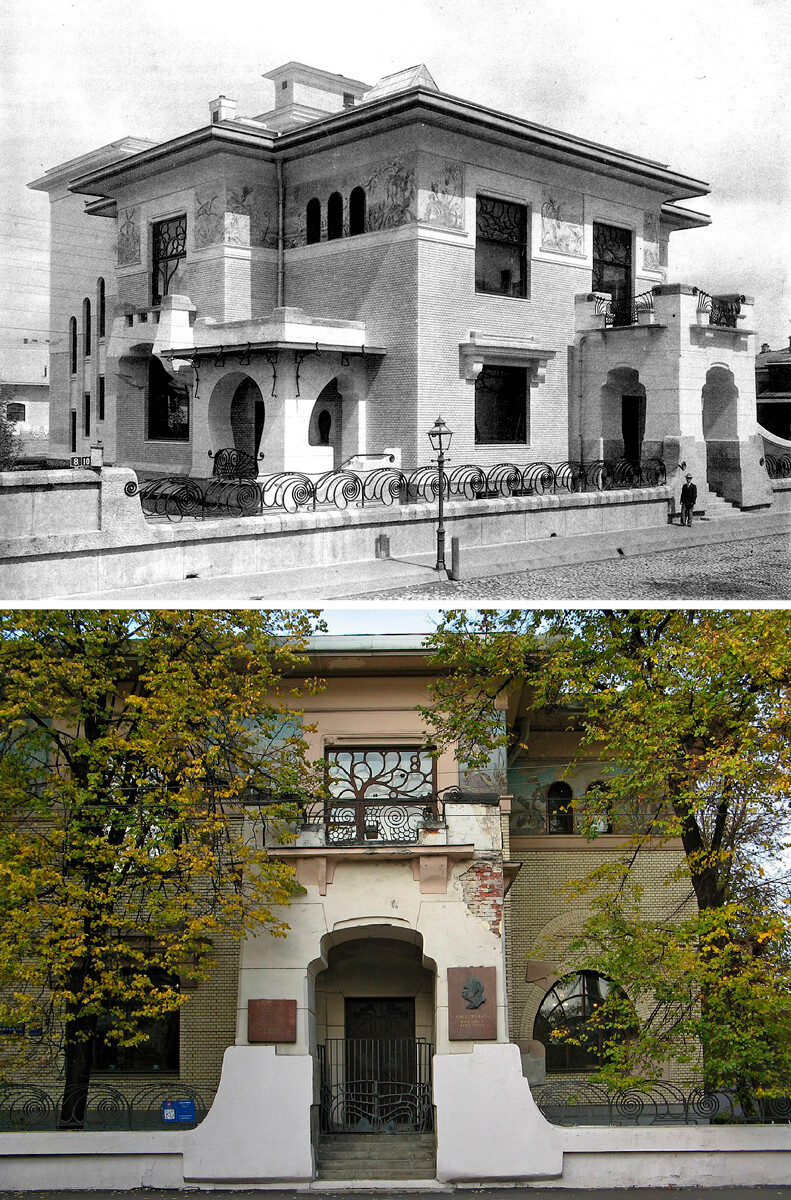

The house was commissioned by businessman and banker Stepan Ryabushinsky. It was built in the Art Nouveau style. It can be characterized by smooth lines, round shapes, while the façade is decorated with mosaics and glazed bricks.

Ryabushinsky’s Mansion in 1902 and now.

Ivan Alexandrov / Public Domain; Ekaterina Borisova (CC BY-SA 4.0)The interior is just as decadent as the exterior. Inside, you can find a grand staircase in the form of a wave, painted ceilings and stained-glass windows. The most interesting room, the chapel, is hidden on the second floor. Elongated windows, a vaulted ceiling and wall paintings reproduce the main elements of the interior decoration of the Orthodox temple.

The grand staircase in Ryabushinsky’s Mansion.

Shesmax (CC BY-SA 4.0)However, not everyone liked the house: “The ugliest example of decadent style. There is not a single straight line, not a single right angle!” This is how children’s book writer Korney Chukovsky once described the house.

Simultaneously with the construction of this mansion, Schechtel was also involved in the reconstruction of the Yaroslavsky Railway Station in Moscow. The building is still considered a great example of Neo-Russian style, a mix of Art Nouveau and old Russian architecture.

Yaroslavskiy railway station.

Public domainIn 1901, Alexandra Derozhinskaya, the daughter of the cloth manufacturer Ivan Butikov, bought the land on which the mansion was built. The heiress decided to build a mansion for herself and her new husband and invited the already popular architect Schechtel.

Derozhinskaya-Zimina’s Mansion in 1902 and now.

Public Domain; MosgornaslediyeThe main element of the façade is an eleven-meter panoramic window with a massive stucco frame. Behind the huge window is a living room with a large marble fireplace lined with marble bas-reliefs of Adam and Eve. According to Schechtel’s idea, the upper half of the living room walls were to be covered with frescoes depicting different seasons, but Derozhinskaya wanted to save money and rejected the proposal. Instead of the frescoes, there was simple white plaster.

Victor Borisov-Musatov restorated pannel in Derozhinskaya-Zimina’s Mansion.

Moscow department of cultural heritageIn addition to its architectural merits, the house was distinguished by the latest technology of its time: telephone service, electricity, sewerage, exhaust ventilation and other facilities, which have not yet had time to spread to all the houses in Moscow.

The son of Pyotr Smirnoff, founder of the ‘Smirnoff’ brand and the vodka king of the Russian Empire, was also named Pyotr. In 1900, the heir bought an empire-style mansion, which did not suit him and instructed Schechtel to redesign the building.

In his hands, the empire style was transformed into art nouveau, but only externally. The façade was changed, the windows were replaced by long and semicircular ones and a bay window was added.

Smirnoff’s Mansion.

Wikipedia / ShakkoInside the mansion, Schechtel created eight halls, decorated in different styles. The Romanesque hall is decorated in stained oak, with mythical creatures and Celtic patterns depicted under the ceiling, while a bas-relief on the fireplace depicts a battle of knights. The Classical Room is decorated in the late Renaissance spirit, with a green marble fireplace and images of mythical creatures on the ceiling.

The fireplace with a bas-relief in Smirnoff’s Mansion.

AnotherLizard (CC BY-SA 4.0)During the construction of this mansion, Schechtel, at the request of Savva Morozov, also engaged in the reconstruction of the Chekhov Moscow Art Theater building (which was then simply called the Moscow Art Theater). The famous philanthropist spent about 300,000 rubles to remodel the building, but Schechtel received nothing - he agreed to the gratuitous work for the love of art. The façade was completely rebuilt, the interior decoration too - the architect redesigned everything, up to the curtains, which became the main symbol of the theater.

Chekhov Moscow art theatre.

A.Savin, WikiCommonsDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox