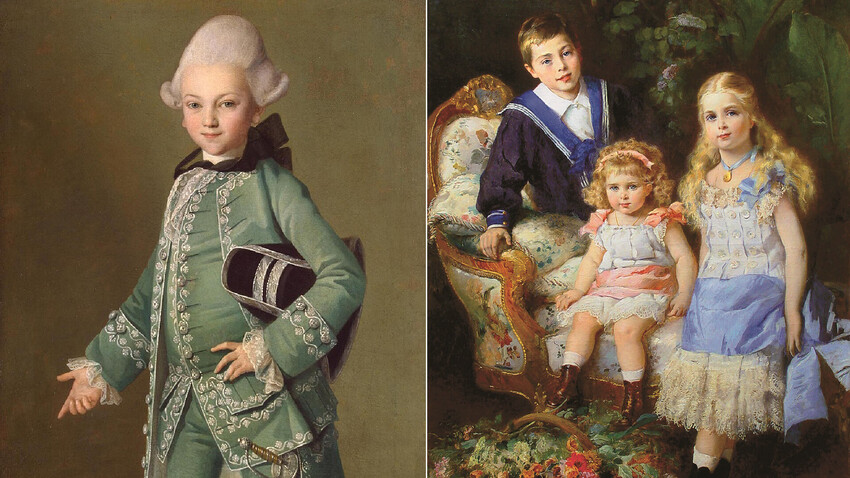

(L) Alexey Bobrinsky, Catherine the Great's son from Grigory Orlov, at 7 years of age (C. L. Christinec, c. 1770) // (R) counter-clockwise from upper left: Georgy, Yekaterina, and Olga, children of Alexander II from Princess Yekaterina Yurievskaya, neé Dolgorukova (by Konstantin Makovsky, 1881).

Hermitage/Public Domain; Konstantin Makovsky/Private collection/Public DomainPeter the Great had multiple lovers and he definitely had children born out of wedlock. His lover Maria Hamilton had two abortions, but the father was unknown. Another lover, Maria Kantemir, allegedly had a stillborn son from Peter.

In any case, miraculously, Peter had no officially recognized bastards. Although, society believed that the outstanding war commander Count Peter Rumyantsev was Peter’s son – because Maria Rumyantseva, the Count’s mother, was known as the emperor’s lover.

The first “official” bastard child in Russian Imperial history was born from Catherine the Great – but it happened before she became the empress and was still a Grand Duchess.

Portrait of Catherine II, 1782, Richard Brompton // Stanisław August Poniatowski, 1786, Marcello Bacciarelli

Hermitage Museum/Public Domain; Lviv National Art Gallery/Public Domain“God knows where my wife gets her pregnancy from, I don’t really know if this is my baby and whether I should take it personally,” said Grand Duke Peter Fyodorovich, the future Emperor Peter III, when he learned about his wife’s pregnancy. And he said it publicly, at least that’s what Catherine wrote in her memoirs.

The baby girl Anna was born in St. Petersburg on December 9, 1757. There was no official reception for foreign envoys on December 17, when the baby was baptized in the palace church. Empress Elizabeth, however, came to the church unofficially to act as Anna’s godmother.

The baby was recognized as a legitimate daughter by Grand Duke Peter Fyodorovich. However, gossip said it was from Catherine’s lover, Stanisław Poniatowski, the future king of Poland. Then, Anna Petrovna died during her second year of life, in March 1759.

Portrait of Catherine II, 1745, Antoine Pesne // Grigoriy Orlov, 1762, Fyodor Rokotov

Coburg Fortress/Public Domain; Tretyakov Gallery/Public DomainAlexey Bobrinsky was born in secrecy on April 11, 1762. He was the son of Catherine and her lover Grigory Orlov and, this time, Catherine managed to hide her pregnancy from her husband, Emperor Peter III. She had to wear a corset and make curtsies at court, all with a child in her womb.

When Alexey was born, he was very weak and he was immediately given away to Vasiliy Shkurin, Catherine’s house servant. In Shkurin’s family, Alexey was raised until the age of 12, when he was sent to the First Cadet Corps and, after completing his military education with a distinction, embarked on a vast journey through Russia and Europe.

We have a separate article about Alexey Bobrinsky and his life, which made him turn from a womanizer and a ruffian into a scientist.

Portrait of Paul I, 1796, Vladimir Borovikovsky; Sophia Stephanova Razumovskij,1780, Franz Ludwig Close ----

Novgorod City Museum/Public Domain; Nationalmuseum, Stockholm/Public DomainSemyon was the son of Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich, born in 1772 from a widowed lady-in-waiting, Sofia Ushakova. Historian Isabel de Madariaga writes that “to make sure that he was able to produce an heir, Pavel was encouraged to bond with a certain compliant widow”, meaning Ushakova. Catherine, who was deadpan practical, wanted to make sure that her son was able to produce an heir.

Semyon was raised in the palace rooms of Catherine the Great. In 1780, when he was eight years old, he was sent to military schools and, eventually, graduated from the Naval Cadet Corps. The first ship Semyon was posted to was a 66-gun sailing ship of the line named ‘Don’t Touch Me’. After a naval battle in the Vyborg Bay on June 22, 1790, Semyon was sent to Catherine with a report. When he arrived at St. Petersburg, Semyon saw his grandmother for the first time in 10 years.

In July 1790, Semyon was promoted to captain lieutenant. There are two versions of what happened next. According to the first, in 1793, Semyon was sent to London to serve in the British Navy. The other version says Semyon was to take part in the Mulovsky expedition (that never happened), but suddenly died in Kronstadt.

The records of the Naval Ministry say that Semyon Velikiy died on August 13, 1794, during the shipwreck of the English ship Vanguard during a terrible storm in the waters of Antilia, near the islands of Sint Eustatius and St. Thomas.

Semyon was nicknamed “the Great” during his lifetime, apparently because of the rumors about his origin. When he died, Alexander Khrapovitsky, Catherine’s secretary, wrote: “The news about the death of Senyushka the Great is received.”

Pavel Petrovich’s second bastard child was born after his assassination as the Emperor Paul I of Russia. A week before Paul’s death, he summoned his highest civil official, Deputy Chancellor Alexander Kourakine. Paul told him in person that two women were pregnant with his children. If they turn out to be boys, they would be named Nikita and Filaret, if girls – Eudoxia and Martha. Paul’s son, Alexander, was to become the children’s godfather.

After Paul died, only one child was actually born, somewhere between May and June 1801, a girl that was named Martha. Her mother, according to the sources, was Mavra Yuryeva, a lady-in-waiting of the Empress Maria Fyodorovna, Paul’s wife.

According to the late Emperor’s will, on August 1, 1801, the baby Martha was promoted to nobility and given several villages with a total of 1000 peasants. She was brought up in Pavlovsk by Maria Fyodorovna. Sadly, Martha lived only a little longer than two years, she died on September 17, 1803. The income from her villages was given to her mother.

Georgiy Alexandrovich Yurievskiy, 1894

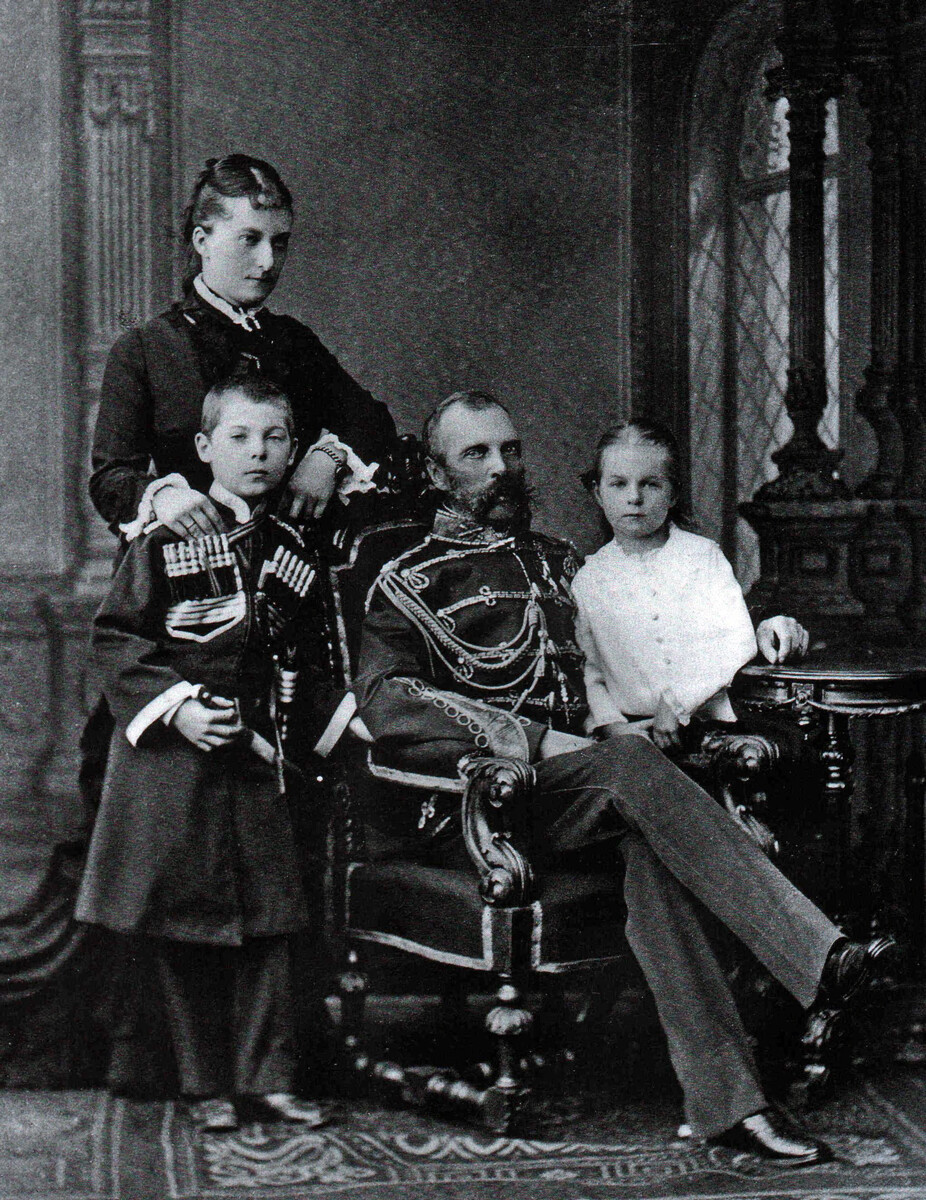

Public DomainGeorgy and two other daughters, Olga and Yekaterina, were born from Alexander II and his favorite Yekaterina Dolgorukova. From 1866, they became lovers, while Empress Maria Alexandrovna was out of the emperor’s favor. After Nicholas, her eldest son with Alexander II, died of meningitis, she lost all interest in life. Alexander’s affair was obvious for everybody in the palace, but the empress stayed silent.

“Destined for forgiveness, day after day, for many years, she never once uttered a complaint or an accusation. The secret of her suffering and humiliation she took with her to her grave,” a lady-in-waiting of the Imperial Court Alexandra Tolstaya wrote of her.

Georgy was born on April 30, 1872, in the Winter Palace. In 1874, he was elevated to the style of Serene Highness by the order of Alexander II. He and his sisters were given the last name Yurievsky, created from Yuri, one of the hereditary names of boyars Romanovs. In 1880, Empress Maria Fyodorovna died and, two months after it, Alexander II married Yekaterina Dolgorukova, who was also given the title Princess Yurievskaya and the style of Serene Highness, as were all their three children. There was another boy born from this union, Boris (1876), but he only lived a month.

After Alexander II was assassinated in 1881, Yekaterina Yurievskaya and all her children left Russia for France. There, Georgy studied at Sorbonne University, but, later, returned to Russia, where he was a lecture attendee at the Naval Cadet Corps. Although Georgy’s half-brother Alexander III didn’t allow him to join the Russian Imperial Army out of pure spite, Georgy managed to gain approval of his other half-brother, Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, who allowed him to serve in the Russian Navy, despite his lack of qualification.

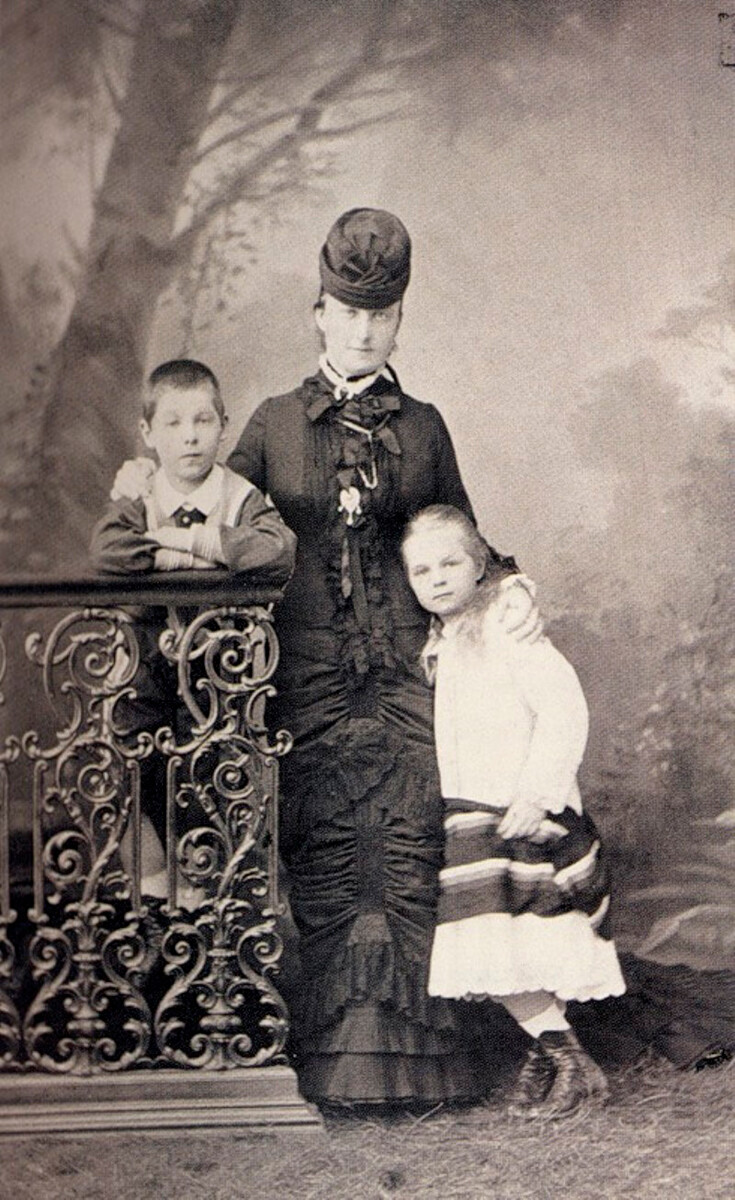

Ekaterina Mikhailovna Yurievskaya (Dolgorukova) with her son George and daughter Olga. 1881-1883.

Levitsky S.L./Public DomainGeorgy performed very poorly. “Both when on duty and on board during cruises, he simply does not want to do anything at all; neither advice, nor the example of others have any effect whatsoever on him. Laziness, untidiness and total lack of self esteem make him the laughing stock of his comrades and draw upon him the dissatisfaction of his superiors, who do not know what to do with him,” Grand Duke Alexei wrote to his mother in 1893. “It seems to me he would do better to transfer to land service, for he will never make a good sailor!” he added.

In 1897, Georgy was discharged from the Navy and sent to serve in His Majesty's Hussar Life Guards Regiment. Alexander III was dead by that time and his son and successor Nicholas II didn’t object to his uncle serving in the Army.

In 1900, Georgy married Countess Aleksandra Konstantinovna von Zarnekau and they had a son named Alexander Yurievsky (1900 – 1988). They went on to live abroad, where their marriage crumbled and Aleksandra divorced Georgy. He died in Marburg in 1913.

Olga Alexandrovna Yurievskaya

Legion MediaOlga Alexandrovna was born from the same union between Alexander II and Yekaterina Dolgorukova in 1873.

From 1891, she lived with her mother and sister in Nice, in a house called Villa Georges in honor of her brother Georgy. In France, the family was able to afford some twenty servants and a private railway carriage.

In 1895, Olga married Count George-Nicholas von Merenberg (1871–1948), a grandson of Alexander Pushkin, becoming Countess Merenberg. Nicholas II, who became the tsar, refused to sponsor his aunt’s wedding, because his mother Maria Fedorovna forbade him to do so and Olga was very offended by that.

She spent most of her life in Germany and had three children, one of which died in infancy. She, herself, died in 1925 at Wiesbaden.

Ekaterina Alexandrovna Yurievskaya (Bariatinsky).

Legion MediaAlexander II and Princess Yekaterina Yurievskaya (nee Dolgorukova)’s youngest daughter Yekaterina was born on September 9, 1878, in Yalta, Crimea, on one of the estates Alexander II gave to her mother.

After 1881, Yekaterina with her mother, brother, and sister went to live in Nice. In 1901, she married Alexander Baryatinsky, who had one of the biggest fortunes in Russia, but was, at the same time, a womanizer and big spender. They had two children, Andrey (1902-1944) and Alexander (1905-1992), who inherited a vast fortune after their father passed away in 1910 from meningitis.

During World War I, Yekaterina returned to Russia. She lived a lavish lifestyle and, in 1916, married Prince Serge Obolensky (1890-1978). However, this marriage was also unhappy. After the Revolution, Yekaterina and Serge had to flee to Europe and barely made a living there – Yekaterina even had to sing in bars to earn something. After her mother died in 1922, her daughter received almost nothing, as the mother lost all her fortune to lavish lifestyle and various charities.

Tsar Alexander II, Duchess Catherine Dolgorukova and their children George and Olga.

Public DomainIn 1923, Serge Obolensky divorced Yekaterina, who went on to become a professional singer, with a repertoire of some two hundred songs in English, French, Russian and Italian. She bought a house on Hayling Island, Hampshire, and lived there, supported by an allowance from Queen Mary, the widow of King George V, but, after the Queen’s death in March 1953, she was left almost penniless and began selling her possessions.

Yekaterina died in a nursing home on Hayling Island on 22 December 1959. She was the last surviving child of Alexander II, as well as the last grandchild of Nicholas I.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox