The Winter Palace and the Dvortsovaya (Palace) square

Legion MediaThe Winter Palace can be described as the heart of St. Petersburg and the most recognizable building in the city. The city’s main square, Palace Square; the grand Palace Embankment on the River Neva; and Palace Bridge - St. Petersburg’s landmark drawbridge - are all named after it. Also, the city’s central street - Nevsky Avenue - starts at the Winter Palace and then heads deep into the city.

Several “winter” palaces were built in the 18th century and the present one is the fifth of its kind. Two “winter” palaces were erected under Peter the Great. The first was temporary and made of wood and, in the second, made of stone, Peter the Great lived out the last years of his life and it was where he died. For a long time, it was considered lost, but, in the 1970-1980s, parts of its rooms were discovered under the Hermitage Theater - now several of them have been restored and are open to visitors.

The Second Winter Palace of Peter the Great

The HermitageEmpress Anna Ioannovna’s residence is regarded as the third Winter Palace. Essentially, this was Peter the Great’s palace, but rebuilt by his niece. Peter the Great’s daughter, Elizabeth Petrovna, wanted an even grander and more spacious palace when she came to power, so a fourth, temporary Winter Palace was built for her… but then it was dismantled and, finally, the present palace was constructed.

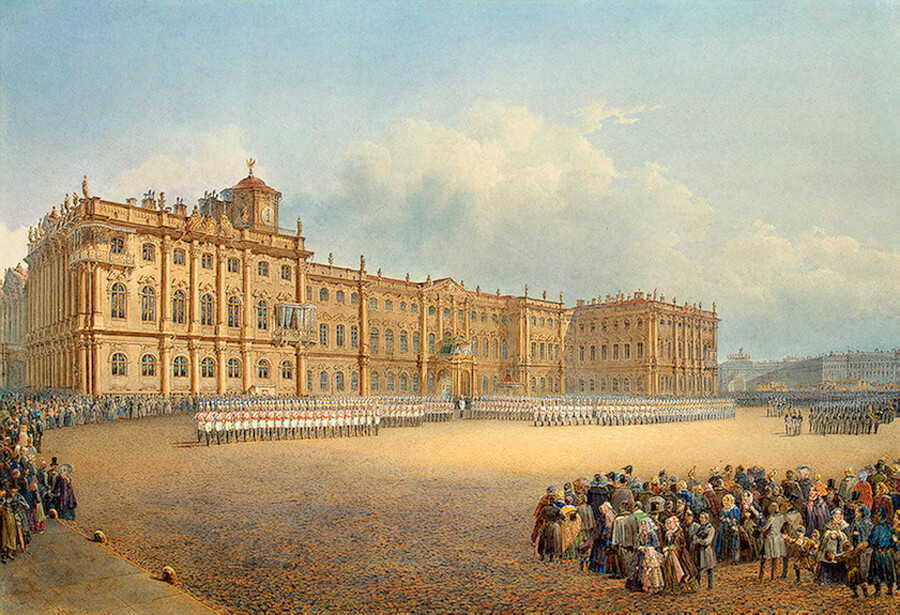

Vasily Sadovnikov. View of the Winter Palace from the Admiralty. The Changing of the Guard. 1830s

Public domainThe final design of the ostentatious Baroque palace was by Elizabeth Petrovna’s chief architect, Italian Bartolomeo Rastrelli. He built more than one palace for her, but this was to be the most magnificent. Its construction took eight years and the Empress did not live to see the work completed.

After the brief rule of Peter III, his spouse Catherine the Great came to power as a result of a palace coup. She, naturally, also decided to have the palace adapted for her. In the mid-1760s, in accordance with her decree, the overdone baroque “frills” in its decor were removed, giving the building a more austere appearance. Catherine also had several rooms rebuilt to accommodate her favorite, Grigory Orlov, as close as possible to her private apartments.

The Winter Palace at night

Legion MediaIt is not called the ‘Winter’ Palace by accident. In summer, the monarchs preferred to retire to the country - each of them had their own magnificent residence and, indeed, more than one - Peterhof, Tsarskoye Selo, Pavlovsk. They all had lavish parks and numerous entertainment was staged there.

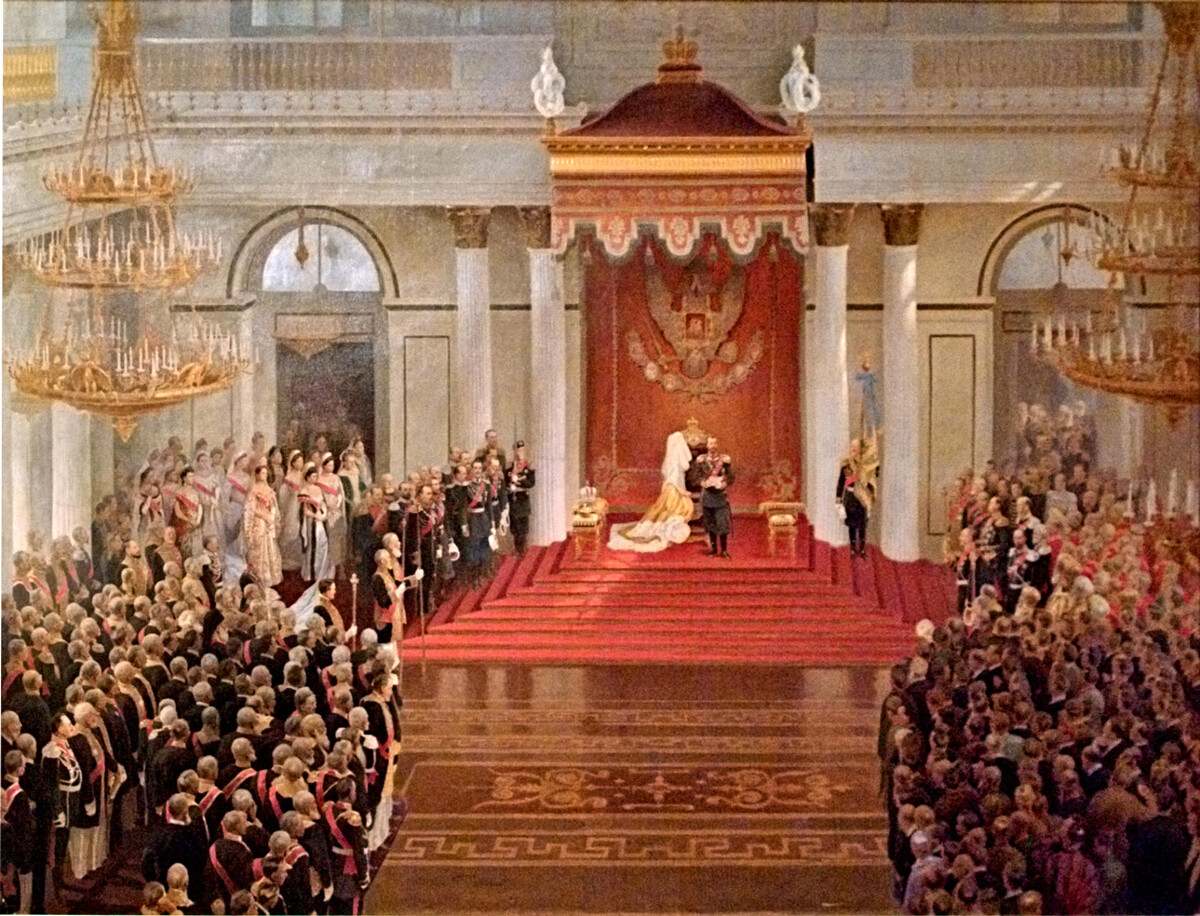

V.V. Polyakov. Reception on the Occasion of the Opening of the First State Duma on April 27, 1906

Museum of Political History of RussiaBut, in winter, all the Tsars of the Romanov dynasty, starting with Catherine the Great, invariably lived in the Winter Palace (incidentally, the palace had over 400 stoves to heat such a large space). It was the principal Imperial palace of Russia, a formal residence with a throne room.

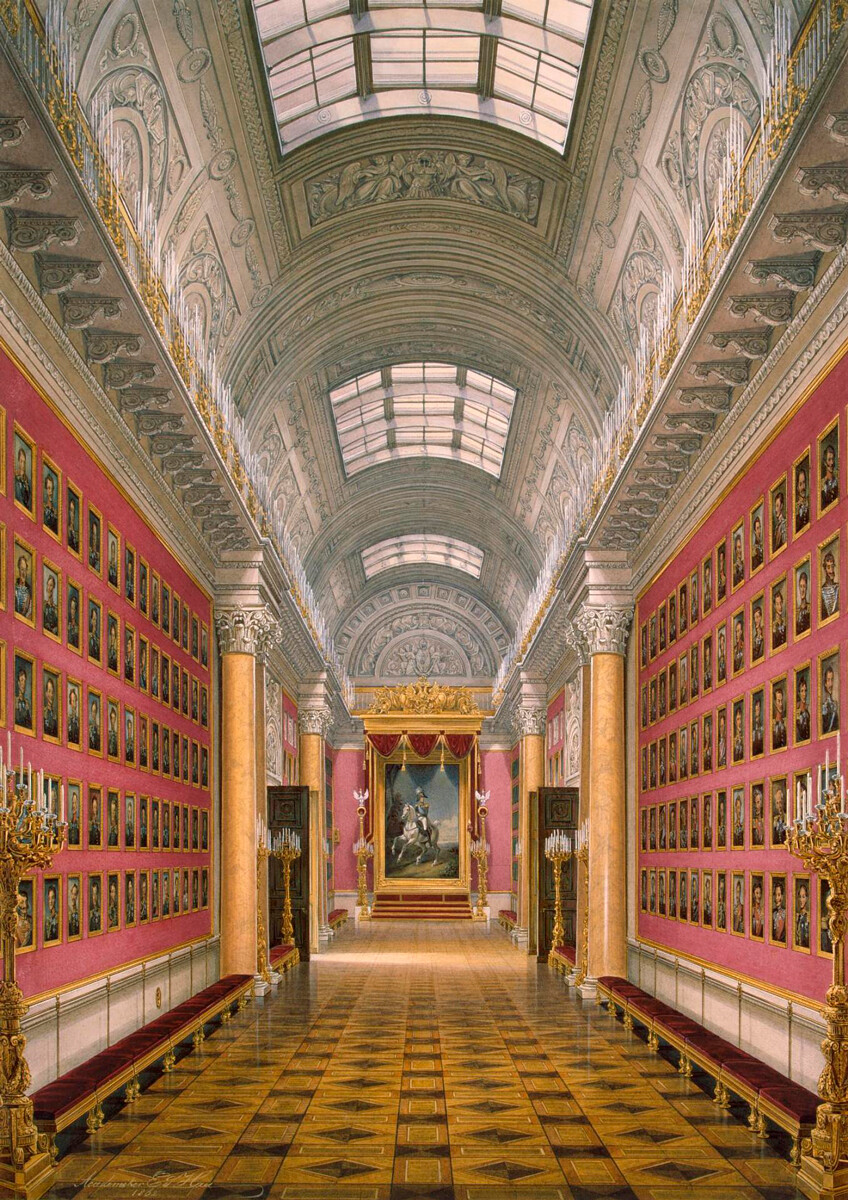

Eduard Hau (Gau). The War Gallery of 1812. 1862

The HermitageAfter the first Russian Revolution in 1905, Tsar Nicholas II no longer wanted to live in the center of St. Petersburg, in the public’s view. He moved the official Imperial residence to the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, where he and his family lived for the next 12 years.

Nicholas II on the balcony of the Winter Palace

Karl Bulla Photography Studio / Central State Archive of Film and Photo Documents of St. Petersburg

View of the Winter Palace and Palace Square

Andrew Shiva / Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 4.0There are three floors in the Winter Palace and its floor plan is rectangular with an internal courtyard. It has four façades (which vary slightly in design). The south façade, facing Palace Square, is regarded as the principal one - it houses the grand entrance, framed with three arches. And the north façade faces the Neva.

The north façade and Palace Embankment

Florstein / CC BY-SA 4.0The building is decorated with two rows of innumerable columns. There are sculptures and vases along the perimeter at roof level.

The Jordan Staircase

The HermitageOn the Neva side, the palace is 210 meters long and 23.5 meters high. Under an Imperial edict issued in 1844, it was prohibited to erect residential buildings higher than the Winter Palace.

The Malachite Room

The HermitageThe Winter Palace has a total of 1,084 rooms. The interiors of the state rooms, private rooms and boudoirs are all works of art in their own right. Each royal personage living in the palace was allocated more than 10 rooms. Separate apartments were allocated to the Consort of the Emperor (after Catherine the Great, the country was ruled only by men). The monarch’s children also lived in the palace and, later, for example, the children’s brides- or grooms-to-be. After the wedding, the newly-weds usually moved to their own palaces.

Eduard Hau (Gau). The bedroom of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, 1870

The HermitageSometimes, several rooms were converted into private apartments to accommodate people of high standing. Also, at the invitation of the Emperor, people not related to the Imperial Family could live or stay in the Winter Palace. The Court staff also lived in the palace, as did the ladies-in-waiting, who were allocated up to three rooms each.

Take a look at the Winter Palace through the eyes of the Emperors here.

Military hospital in the Nicholas Hall of the Winter Palace

Public domainDuring World War I, by order of the Emperor, the empty rooms of the palace after it was vacated by the tsarist family were handed over for army use. A military hospital named after Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich was opened there in 1915. Around 1,000 beds for wounded servicemen were installed in six rooms of the tsarist palace and there was also a separate operating theater. The empress herself and her daughters were medical nurses, helping to dress the wounds of the injured.

More photos here.

Still from the movie ‘The Storming of the Winter Palace’, 1920

Public domainThe key event of the 1917 October Revolution when power was transferred to the Bolsheviks was the “storming of the Winter Palace”. The well-known newsreel shots showing soldiers running towards the palace are merely a dramatic reconstruction. In actual fact, the Winter Palace was seized pretty much peacefully - the discharge of a number of artillery guns merely scratched the palace’s cornicing and the cruiser ‘Aurora’ fired off a single blank round. The Provisional Government, which was housed in the Winter Palace, was very poorly guarded and someone had completely forgotten to close the rear gate, so those storming the building got into the palace without bloodshed and arrested the government.

A room in the Winter Palace during the war. Workers left picture frames in their place in order to be able to rehang the evacuated masterpieces more quickly.

The HermitageOn June 22, 1941, museum staff started urgently to prepare the collection for evacuation. In the course of a month, more than a million works of art were packed and shipped. But far from all were evacuated, since the Siege of Leningrad was already under way by September 1941.

The coach house after bombing

The HermitageBomb shelters were set up in the rooms and basements of the Winter Palace, where up to 2,000 people sought refuge from shelling and air raids. Many members of museum staff permanently lived in the palace with their families, while at the same time continuing to work to protect the remaining exhibits. The Winter Palace repeatedly came under fire: Certain rooms and the grand staircase were severely damaged, while a shell hit the tsarist coach house.

In 1944, following the lifting of the siege, the Winter Palace opened its doors to visitors again, but restoration and rebuilding were to continue for a long time.

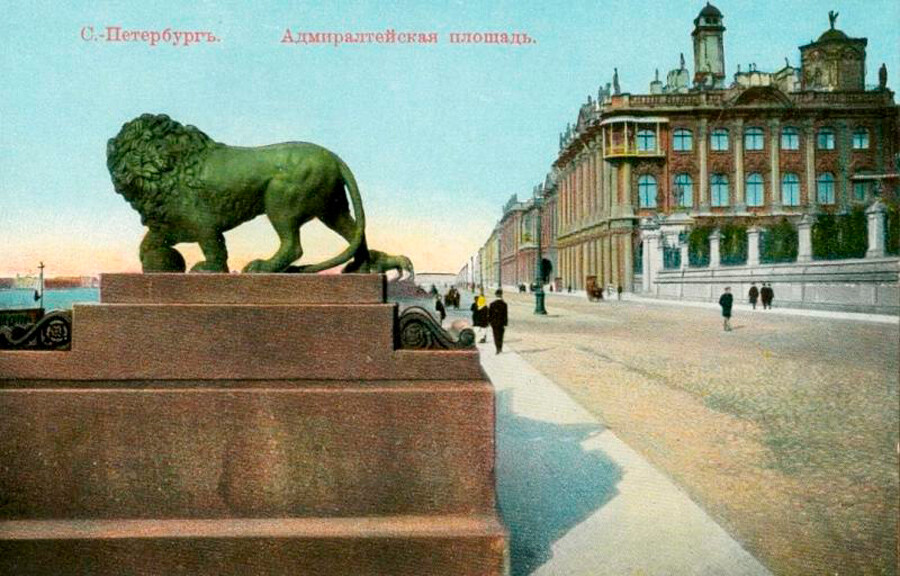

Postcard, late 19th century

MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruUnder Catherine the Great, the palace was painted a sand color like the residences of the French kings and Austrian emperors. In the mid-19th century, Nicholas I ordered the color of the façade to be changed to brick red and that was how the palace looked when the Revolution broke out.

In all likelihood, the Russian tsars never saw a green Winter Palace

Lynn Greyling / PixabayIt became pistachio green with white columns during the Soviet period, in 1946 - the result of post-war restoration work.

The White hall

The HermitageThe Winter Palace is the main building of the country's leading art museum, the Hermitage. But it is far from its only building. The year 1764 is regarded as the date of the foundation of the Hermitage - in that year, Catherine II acquired an enormous collection of paintings. She added a wing to the Winter Palace known as the ‘Little Hermitage’ (i.e. place of solitude) to house it.

The War Gallery of 1812

Eduardo Fuster/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesThe collection grew ever larger and, as a result, another, more substantial building, known as the ‘Large Hermitage’, was erected specially to serve as a museum. Strictly speaking, the Winter Palace itself only became a museum in the wake of the Revolution - part of the collection was moved here and access passages linking it to other adjacent wings were built. The Hermitage is the country’s biggest and most-visited museum and houses priceless objects of Western and Russian art (here are the top masterpieces).

Cats live in the basement of the building

Legion MediaThe Hermitage cats are the museum’s unofficial symbols. The first ones appeared in an earlier “version” of the Winter Palace - they were brought from Kazan in 1745 to help deal with mice and rats. And they protected the state apartments against the latter better than any poison. In the siege of Leningrad, many of the cats died - subsequently around 5,000 cats were sent to the Hermitage by the people of Siberia. Museum director Mikhail Piotrovsky is a firm supporter of the feline presence, describing the cats as a “legend” of the Hermitage and an “integral part” of the life of the museum.

More on the Hermitage cats can be found in our report here.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox