Who guarded the lives of Russian tsars?

The members of the Palace Grenadiers Company

Public domainMarch 1st, 1881, the day Alexander II was assassinated, was apparently the worst day for the Russian Emperor’s personal security guards. But it could get worse, because Russia could lose the next Emperor, Alexander III, as well. Sofya Perovskaya, member of the ‘Narodnaya Volya’ terrorist organization, started planning for the assasination of Alexander III immediately after the murder of his father. In fact, she was arrested 10 days after Alexander II’s death near Anichkov Palace, where Alexander III lived with his family.

Alexander III’s security – best in the Empire

His Majesty's Cossack Escort (photo), 1890s

Public domainThe rule of Alexander III, who came to the throne right after his father was blown up, was the time when the Emperor’s security got strengthened. Alexander III chose Gatchina Palace outside St. Petersburg as his main residence – in Gatchina, it was easier to maintain security measures than in the very center of St. Petersburg, where the Winter Palace is located. Separate regiments were formed for guarding the Imperial residences and the Imperial family in railroad trips. The 1st Railroad Battalion, guarding the Emperor, counted over 1000 men – they acted as both train crews and railroad security.

Before Alexander III, the Emperor’s trains weren't closely guarded, which made it possible for the terrorists of Narodnaya Volya to try to blow it up. Under Alexander III, any trip by the Emperor on the train was a close-knit security operation. All information about the Emperor’s trips was classified, and two completely identical trains, which periodically switched places, traveled simultaneously along the planned route.

His Majesty’s Own Cossack Escort. Uniforms.

Public domainFrom 1881, military units were organized in such a way that, during the passage of the Emperor’s trains, practically every meter was guarded. Vasiliy Krivenko, a secretary for the Minister of the Imperial Court, remembered: “With each tsar’s railroad trip, great pressure was laid on entire military districts to perform the task of protection... Tight military cordon in fact stretched from St. Petersburg to the Crimea, or even to the Caucasus, if the Emperor needed to go there. During the passage of the train through a region, all kinds of training and drill classes in the local military formations were stopped, all the attention of the authorities was focused on the rail track and on the train in which the tsar proceeded.”

But the security of the Russian sovereigns wasn’t always so tight.

Peter’s problem with security

The streltsy of Moscow

Public domainIn February 1697, a plot was revealed against the life of Tsar Peter. The conspiracy was led by a senior statesman, Ivan Tsykler. He and his accomplices noticed that Peter often went and rode around Moscow alone, without security guards, and planned to catch and stab him. Luckily, their plan was derailed by Elizaryev and Silin, two ordinary streltsy, members of the palace guard.

Streltsy – those bearded men dressed in red overcoats and fur-trimmed hats, wielding axes or spears – were the bodyguards of the tsars of Moscow. In the Kievan Rus’ and beyond, the security of the princes was ensured by their druzhina – the closest circle of fellow noble warriors. When the Moscow Tsardom was created in 1547, the tsar started hiring the military to serve as his personal bodyguards and security at the Royal residences, including the Moscow Kremlin.

Now, Peter’s problem with his security was that Ivan Tsykler, the head of the conspiracy, was a former streltsy colonel, and the streltsy killed Peter’s uncle and other relatives in the 1682 uprising that put Peter and his brother Ivan on the throne. Peter dismissed and destroyed the streltsy in 1698, with the suppression of their uprising – one of the most gruesome executions of the era.

After that, the tsar’s personal security was ensured by his new guard regiments – the Preobrazhensky and Semyonovsky. Former troops in his ‘Toy Army’, in 1700, the two regiments were promoted to Leib Guard (“Lifeguard” in German) and became the Tsar’s personal security. During the reign of Anna Ioannovna, the Izmailovsky and Konnyi (Cavalry) regiments were added to what became the Imperial Guard.

From the Imperial Guards to the Cossack Escort

The Life Guard Preobrazhensky regiment (uniforms)

State Historical MuseumIn the 18th century in Russia, the Imperial Guard played an important role in the ‘Palace Revolutions’ – Catherine I, Peter II, Anna Ioannovna, Elizabeth Petrovna and, most famously, Catherine the Great, ascended the Russian throne with the help of the Imperial Guards. The Guards had become a serious political power, which, by the end of the 18th century, wasalso so corrupt that it was actually possible to instill a conspiracy inside their ranks, and execute the murder of Emperor Paul I.

Alexander I, Paul’s son and heir, removed the Imperial Guards from immediate protection of the Imperial Family. In 1811, Cossacks from Southern Russia and the North Caucasus were summoned to the Imperial Guards to protect the Emperor during the European Campaign of 1813-1814 (the War of the Sixth Coalition). They formed a squadron inside the Life Guard Cossack regiment.

"The attack of the Life Guard Cossacks near Leipzig on October 17, 1813"

Karl RechlinDuring the Battle of Nations at Leipzig, Saxony, on October 16-19, 1813, the Cossack squadron actually saved Alexander I’s life. During the battle’s culmination, the Cossacks under Colonel Yefremov performed a flank attack at the French Cuirassiers (heavy cavalry) who attacked the positions at Alexander’s headquarters. Even the Cossack officers were armed with spires in order to make the attack nastier. They crushed the French cavalry.

In 1825, the Decemberist Revolt occurred, raising further concerns about the Imperial Family’s security. Nicholas I improved it greatly. In 1828, he formed His Majesty’s Own Cossack Escort, staffed by over 40 young North Caucasian noblemen – Cabardians, Chechens, Kumyks, Nogais and other Caucasian ethnicities. Why were they chosen over Russian guards?

Mountain men behind the Emperor

Alexandra Fyodorvna, Nicholas II (wearing a Cossack uniform), and the Cossacks of the Escort, Livadia, Crimea, 1913

Public domainIt’s important to remember that the Escort was formed during the Russian annexation of the North Caucasus – the Caucasian War of 1817-1864. Historian Dmitry Klochkov explains: “Serving in the capital of the Empire, the young Caucasian noblemen who came from strictly traditional societies, became accustomed to European traditions and morals. The lower ranks of the Escort were renewed every four years to ensure the rotation of personnel.” As Nicholas I reckoned, entrusting the Caucasian noblemen with the protection of the Emperor was a gesture meant to gain their confidence and respect. But at the same time, these young offspring of the Caucasian princes were in a sense hostages, held in the heart of the Empire, next to the sovereign himself.

The Cossacks of the Escort (uniforms)

Public domainThe uniforms of the Cossacks of the Escort had ethnic design: a traditional woolen coat called cherkeska (chokha), equipped with the famous gazyrs. They were armed with daggers and shashkas (Coassack sabres), and sometimes even sported bows and wore chainmails. The Cossacks of the Escort were ‘gala’ guards of the Emperor, picturesquely following him in all their glory during military parades and ceremonial receptions at the Imperial Court.

But they could do much more than that. The Caucasian Cossacks could aim and shoot accurately from horseback, grab a handkerchief from the ground with their shashka and keep it, ride standing on the saddle, and crawl under the belly of a horse – and all of these at full gallop! The Escort was an object of admiration for the court nobility. But there were certain rules of treating the Caucasian noblemen, devised by Alexander Benkendorf, the head of Nicholas I’s state security. He strictly prohibited the Russian noblemen from ridiculing the Cossacks for their religion or their looks, forbade Russians to interfere with the Caucasians’ religious needs, and most importantly, not subject them to corporal punishment.

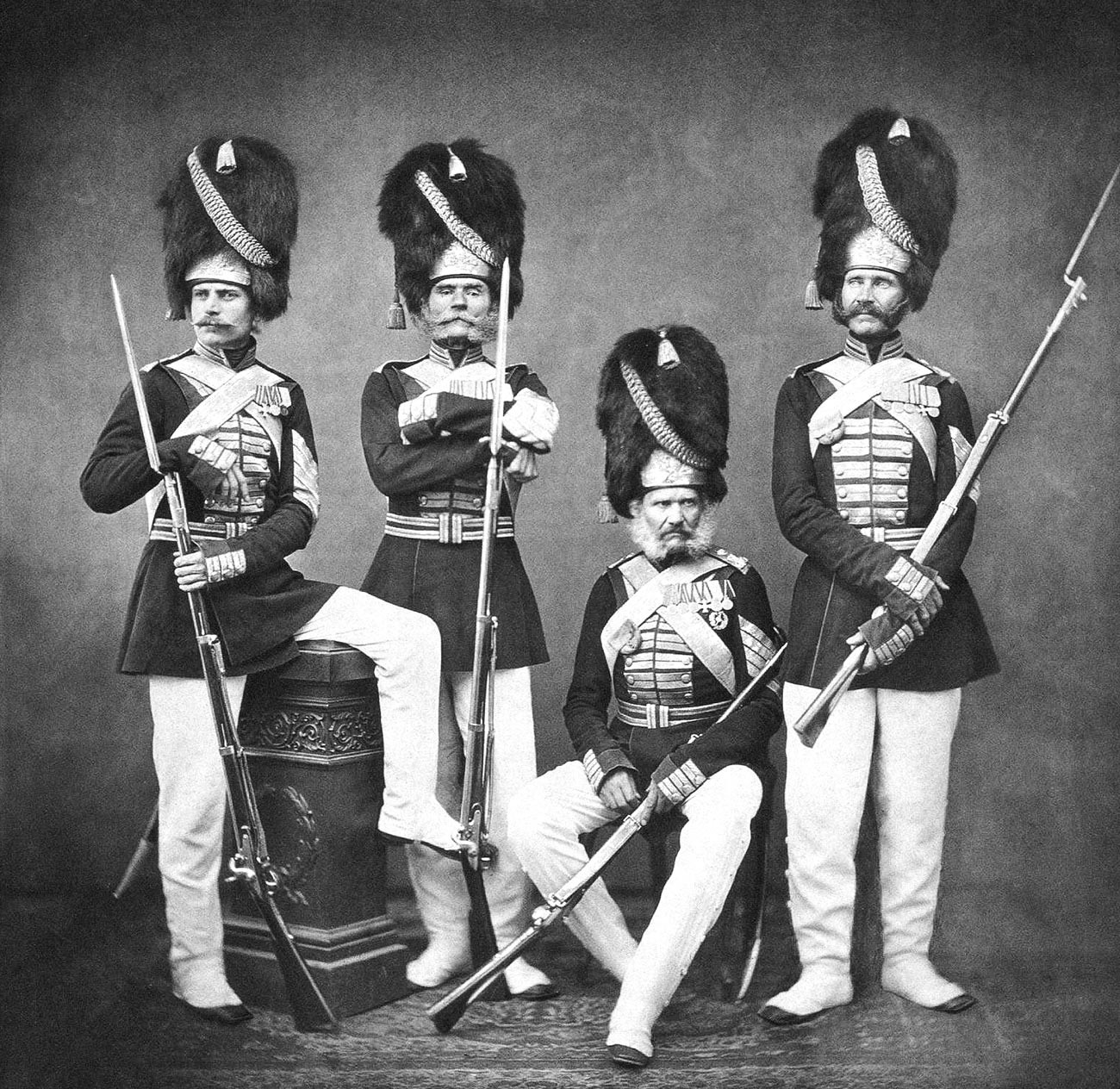

The Palace Grenadiers circa 1870-1880

Public domainIn 1827, in addition to the Cossack Escort, the Company of Palace Grenadiers was formed. Their main function was keeping honorary duty in the palaces, near the monuments to the Emperors, during ceremonial feasts and receptions. The Grenadiers Company was staffed with seasoned, aged warriors wearing bright, gold-and-red uniforms. For common people and foreign guests, those grenadiers were the embodiment of the Empire’s military glory.

Special Cossacks were entrusted with guarding the Empress – two to four Chamber Cossacks. Historian Igor Zimin says: “Handsome tall Cossacks, with an indispensable beard, were selected for this position. They wore luxurious uniforms, and were happy to show it during foreign voyages, since in Europe, the Chamber Cossacks were the literal personification of the terrible, menacing Russian Cossack.”

The Emperor's children and the Cossacks of the Escort, 1913

Public domainHis Majesty’s Own Cossack Escort existed until 1917. However, during the revolutionary times in Russia, no security could ensure the Emperor’s safety in the vast Winter Palace in the center of St. Petersburg. So Nicholas II and his family stayed at their suburban residences in Peterhof and Tsarskoye Selo; for example, in 1905-1909, Nicholas visited St. Petersburg, the capital of his Empire, only four times! The residences were cordoned and constantly checked by patrols. But this didn’t save Nicholas II from all of the ensuing events, because the real security of the Emperor lies in the trust of his subjects.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox