8 life-changing reforms in Russian history

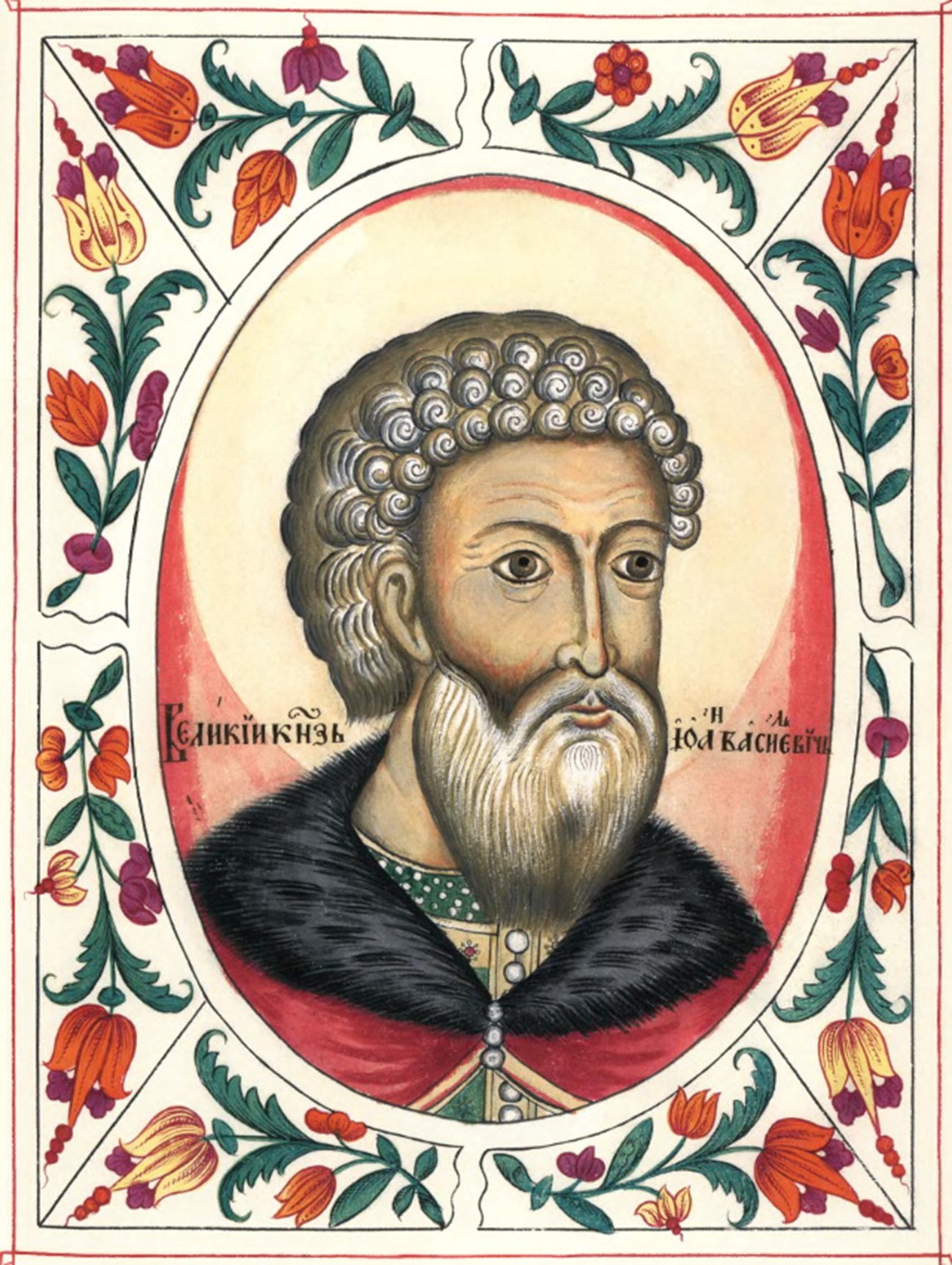

1. Ivan the Great’s ‘Gathering of Rus’ lands’

Ivan III

Public domainIvan III (also known as Ivan the Great) was a Grand Prince of Moscow who ascended to the Russian throne in 1462. He is sometimes referred to as the “gatherer of the Russian lands”, because he greatly expanded the territory of his state after the Mongols’ dominance had ended.

Ivan III subordinated Rus’ principalities to Moscow, united these lands under one monarch and attempted to introduce in a basic form a system of state governing bodies known as ‘prikazy’ (from the Russian word “to order”), institutions akin to modern ministries that coordinated policies across different spheres of life and across different regions of the country.

2. Ivan the Terrible’s expansion of Russia and conquest of Siberia

Ivan the Terrible

Stanislav Rostvorovsky/Ekaterinburg Museum of Fine ArtsWhen Ivan IV became the first Russian Tsar in 1547, his quest for power had only just begun. Not only he was set to expand Russia’s territory — through the conquest of Kazan and the Astrakhan Khanates, Siberia, and other territories — but he also ventured to solidify his own rule over these territories by elaborating the system of public administration (‘prikazy’) introduced by Ivan III.

Ivan IV also gathered the Council of a Hundred Chapters, an important forum of the clergy that was set to resolve many questions and issues concerning the problems of the Russian Orthodox Church. This council issued its decisions under the name of ‘Stoglav’, a text that became the manual and reference for Russian clergy in many aspects.

Under Ivan the Terrible, the ‘Sudebnik’ of 1550 was issued. It was the first code of laws in the Moscow Tsardom that was to be obeyed as the only and the highest code of laws, superior to any and all local laws and acts.

Click here for 7 interesting facts about Ivan the Terrible, Russia’s first tsar.

3. The monetary reform of Alexey Romanov

Alexey Romanov's ruble

Public DomainBefore 1654, the financial system in Rus’ was rudimentary: large-scale transactions were complicated, because there were no coins of large denominations; instead, people had to count thousands of small coins. At the same time, small-scale trade was inhibited by the absence of small change. This inflexibility of the monetary system dramatically restrained the necessary economic development of the country.

Tsar Alexey Romanov, spurred by negative consequences of war and plague outbreak, became the first Russian ruler to introduce a ruble coin in Russia. It’s interesting that, in the absence of the mining industry and precious metal production in Russia, there was not enough precious metal to make those coins and first rubles were actually made from remelted European thalers. Although initially, the monetary reform was poorly implemented and resulted in inflation and increased tensions with various subjects, it was a crucial first step that allowed his descendants to advance Russia’s financial and economic system in later years.

Alexey Romanov is also widely known for his reform of the military. During his reign, military specialists from Europe came and settled in Russia, assuming various posts in the army. It also became possible for commoners to become nobility through military service.

Click here to see the top 5 most valuable coins of Tsarist Russia.

4. Peter the Great’s making of the Russian Empire

Peter the Great

Nikolay Dobrovolsky/Central Naval MuseumPeter the Great became the first-ever Russian ruler to visit European countries. The first time he embarked on such a journey was in 1697–1698. There, he learned that Russia lagged behind most European countries in practically all spheres: social, economic, cultural and, most importantly, military.

Upon his return, Peter set out to radically reform all spheres of life in Russia — an initiative that would eventually turn the country into an Empire comparable in power and influence to the major European powers.

Peter the Great initiated the development of various industries that either did not exist in the country before or were not fully developed or present on a large national scale. For example, shipbuilding and silk spinning. He subjected the powerful church authorities to the Most Holy Synod — the newly established highest governing body of the Russian Orthodox Church. The first Russian emperor introduced ‘The Table of Ranks’ in 1722 for state civil and military servants that was meant to foster meritocracy in the army and government. He established the ‘Collegiums’ — specialized state governing bodies akin to modern ministries, — reformed the military to build a powerful army and fleet and introduced Russians to the European way of life, including shaving and wearing European-style clothing.

On top of it all, St. Petersburg emerged as a result of his will as a city that was meant to cement Russia’s status as a European power.

Click here to find out why the Russian Empire owes so much to the Netherlands.

5. Catherine the Great’s Charter to the Gentry

Appearance of Catherine II

Alexandre BenoisAlthough it was her husband, Peter III, who initially freed the Russian gentry from otherwise obligatory service in the army, the gentry fully blossomed as a social class only years later during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762-1796).

The Empress issued the document — known as the ‘Charter for the Rights, Freedoms, and Privileges of the Noble Russian Gentry’ — that granted special privileges to the class of Russian gentry. Most importantly, the gentry was exempt from obligatory military service, received a special status under Russian law, received the right to trade (even overseas) and obtained the right to form local self-governing bodies (subordinated to the Empress and her authorities, nonetheless).

The reform changed life in the Russian Empire in many important ways and, in a way, greatly contributed to the rise of classic Russian culture as we know it today.

Click here to find out what was so "Great" about Catherine.

6. Alexander II’s emancipation of the serfs

Reading of the Manifest

Boris KustodievIn 1649, the Tsardom of Russia published its first legal code forbidding peasants to leave their masters at any point. At this point, the serfdom was emerging as an accepted way of life in Russia. Selling peasants was an acceptable practice among Russian nobility, who had a right to punish their serfs for misdeeds, too.

In 1861, Alexander II — who went down in history as Alexander ‘the Liberator’, albeit for a different reason — abolished serfdom in Russia, although in a drastically inconsiderate way. The state loaned plots of land to newly freed peasants on a 5-6 percent annual interest and thus created a new financial dependency. As a result, the reform that had begun with the best intentions in mind indirectly created conditions that made Russia prone to the revolution that eventually toppled the house of Romanovs in 1917.

Click here to find out how abolishing serfdom led to the Russian Revolution.

7. Industrialization and collectivization in the USSR

Collectivization

Mikhail Smodor/russiainphoto.ruWhen the Soviets came to power, as a result of the Bolshevik Revolution, life in the country changed dramatically. The new authorities immediately nationalized all banks and large enterprises and declared that land should only belong to peasants and factories — to workers.

Yet one of their most far-reaching reforms was, arguably, the politics of industrialization and collectivization. In 1927, a decision to unite dispersed individual farms into large collective farming entities was passed. By the end of 1937, 93 percent of individual farms were forced to become parts of larger “kolkhozy”, taking the country’s agricultural industry to whole new levels of mass production, albeit at enormous human cost.

Also, the new government had to take radical measures to boost the country’s industrial development that was insufficient for its time. Specifically, the major attention was given to developing defense and military, as well as other heavy industries. As a result of these reforms, Russia — or the Soviet Union at the time — quickly overcame many socio-economic problems that contributed to the collapse of the Tsarist regime, but also established a totalitarian form of government that would survive for many decades.

Click here for a journey through the Soviet 1930s in only 17 photos.

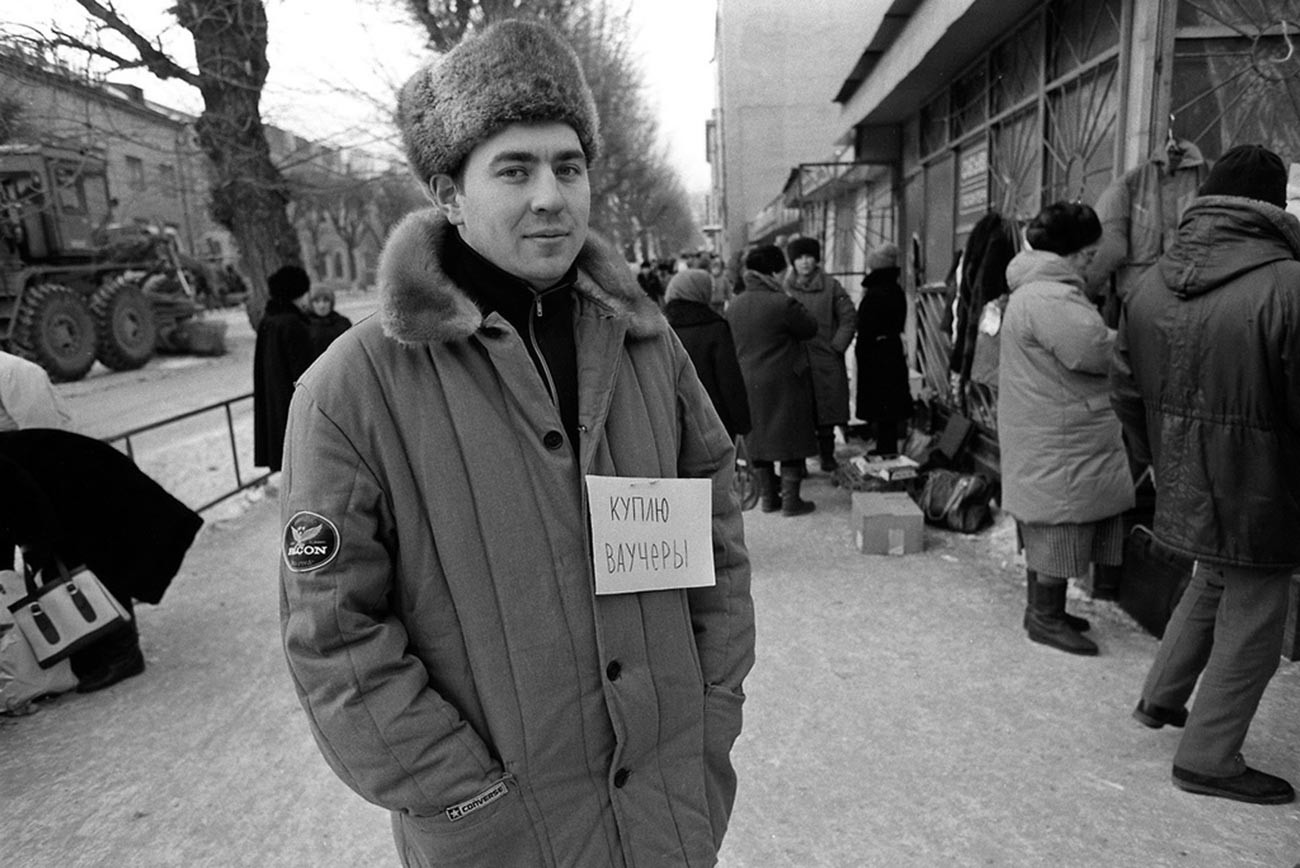

8. Privatization and the switch to a market economy

In the Soviet Union, the economy was regulated by the state. Volumes of production and prices were set by a central authority — the state — who owned most of the factories, plants, and other means of production. However, in 1991, Russians, unexpectedly for most of the people, found themselves in a, more or less, free market economy overnight as the Soviet Union collapsed.

The old socialist economic system was declared inefficient and the new government had to adopt radical measures to facilitate Russia’s survival in the new, capitalist world.

Justifying the need for immediate radical measures by the desire to prevent a possible food crisis (a controversial justification that was later criticized by some economists), economist and government official Egor Gaidar convinced Russia’s President Boris Yeltsin to implement immediate liberalization of the inflating national currency — the Russian ruble — and privatize most of the state-controlled assets to solve the mounting problem of a bulging budget deficit.

The radical reforms were implemented swiftly in the following years. Currently, there is no dominant opinion in Russia on whether the Gaidar’s reforms were good or bad for the country. On the one hand, the time of implementation was marked by inflation, product deficit and high unemployment. On the other, the measures were instrumental in introducing a market economy in Russia and integrating the country’s economy into the world market.

Privatization, too, was marred by controversy, as the process of selling state-owned assets was heavily corrupted and had given rise to the class of oligarchs in Russia.

Click here to find out why it was so dangerous to live in Russia in the 1990s.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox