How the Soviet Union brought culinary equality to the table

The chefs of the workers' canteen of the food production facility getting ready for the service provision to workers, 1986.

Boris Klipinitser/TASSMany dishes that we today consider traditional Russian cuisine are actually rooted in the Soviet times. Salads drenched in mayonnaise, cutlets full of bread, “potato” cake from rusks – all of these were created during the existence of the USSR. The new times challenged the old way of life. And of course, a centuries-old Russian cuisine has also undergone significant transformation.

No kitchen slavery anymore

Until the 1917 Revolution, Russian cuisine was divided both socially and geographically. Traditional peasant dishes from the western part of the Russian Empire included schchi (cabbage soup), millet porridge, and rye bread. Inhabitants of the Russia’s north cooked ukha (fish soup), baked turnips, and kalitki pies. Muscovites enjoyed sbiten (a hot honey drink) in traktirs (a kind of café), while in St. Petersburg, then the capital of Russia, there were elegant cafés and bakeries in the European style. And of course, there was the home cooking of the middle class.

The builders of the Baikal-Amur mainline during the break.

Edgar Bryukhanenko/TASSThe Soviet Union standardized Russian fare. A high level of social equality - an idea peddled by Soviet leaders - became key in cooking. The Soviet kitchen was a mix of national dishes from the socialist republics, many of which were simplified using cheap ingredients. Specialities from the southern region of the USSR, like shashlik, lecho, kharcho were especially popular.

As the proletariat became the main social class food was designed according to the needs of the working class. Moreover, a woman’s role was seen as a worker, not only as a housekeeper. "No kitchen slavery" was a popular slogan of the new country.

The first thing that changed significantly was urban public catering. A working person had no need to eat a lunch at home. He could eat at a canteen in his factory or office, where all dishes were cooked according to the state standards (GOSTs), that regulated everything from the quantity of meat in the soup to the chemical composition of forks. That’s why borsch in Perm was very similar to the borsch in Ryazan, for example. Dishes did not really vary from one place to the next.

Secondly, the term “set lunch” appeared, which described a meal with three courses: Soup, main, and compote. It was cheap so workers would choose this way of dining over cooking at home.

The interior of Moscow's Prague Restaurant.

Yury Artamonov/SputnikOf course, there was public catering for the “elite,” artists, the Party’s nomenklatura, that included not only canteens and cafés but also shops with deficit goods. As for restaurants, ordinary Soviet people visited them mostly during big events like anniversaries or weddings.

Thursday was fish day

There was lack of products in the Soviet Union, in particular meat. That’s why in 1932 the head of procurement of the country, Anastas Mikoyan, introduced “fish day” every Thursday. Canteens served only fish soup, fried cod, and fish cutlets on the fourth day of the week. Why Thursday? For Orthodox believers, Wednesday and Friday are days of fasting. According to one theory, Bolsheviks introduced “fish day” on Thursday to disrupt this religious tradition.

From the end of the 1930s, the fish industry developed rapidly and canned fish (tuna, humpback salmon, and sardines) found a place on tables of Soviet citizens.

The Murmansk fish processing plant, 1971.

Semyon Maisterman/TASSAt first, people were not enthusiastic about these unknown products, wrote food historian Pavel Sutkin. But during one Party meeting, senior Soviet politician Vyacheslav Molotov made a sensational statement. A band of smugglers was allegedly hiding jewels in cans of fish and sending them abroad. As evidence Molotov opened a can and took out a pearl necklace. Needless to say, all canned fish was sold out in the Soviet Union within days - it was practically a lottery. Did anyone get lucky? No one knows. A lot of fish dishes were invented as a result though.

Why the Soviet Olivier is more popular than a traditional salad

The Soviet Union is famous for its fast and affordable developments in cooking. Take, for example, the Olivier salad, which throughout the world is known as the Russian salad. It was originally invented in the 1860s by French chef Lucien Olivier who owned a restaurant in the center of Moscow. The salad was a signature dish of this restaurant. Back then it comprised pressed caviar, boiled crayfish, veal tongue, grouse, soy of anchovy (does anyone know what is this?), fresh salad leaves, pickles, capers, boiled eggs, and fresh cucumbers. To prepare the sauce a cook needed a French vinegar, two fresh eggs, and olive oil.

The Russian salad.

Global Look PressThe Russian salad has nothing to do with the creation of the French chef. But ask any person from modern Russia or the former Soviet republics how they do Olivier, and they will all answer: Boiled sausage, potatoes, canned green peas, eggs, cucumber, and lots of mayonnaise. In the Soviet years, it was not only hard to find delicacies like crawfish and grouse, but also good sausage and canned peas. Sometimes shops "threw" rare products that were immediately snapped up and saved as a treat for the holidays. Today some restaurants try to recreate the original Olivier recipe; however, the Soviet salad made from these ordinary products is much more popular than its Imperial Russian ancestor. A Russian joke: "Don't touch it – this is for New Year!" Everyone in the country gets this joke.

Another famous dish from the USSR is “herring under a fur coat.” Pieces of herring are covered with a layer of boiled potatoes, carrots, beets, grated egg, and encased (of course) in mayonnaise. The salad invented in 1918 was named in the spirit of the Revolution: "Boycott and Anathema to Chauvinism and Collapse," abbreviated in Russian as SHUBA (the fur coat). And still, this dish decorates every Russian festive table.

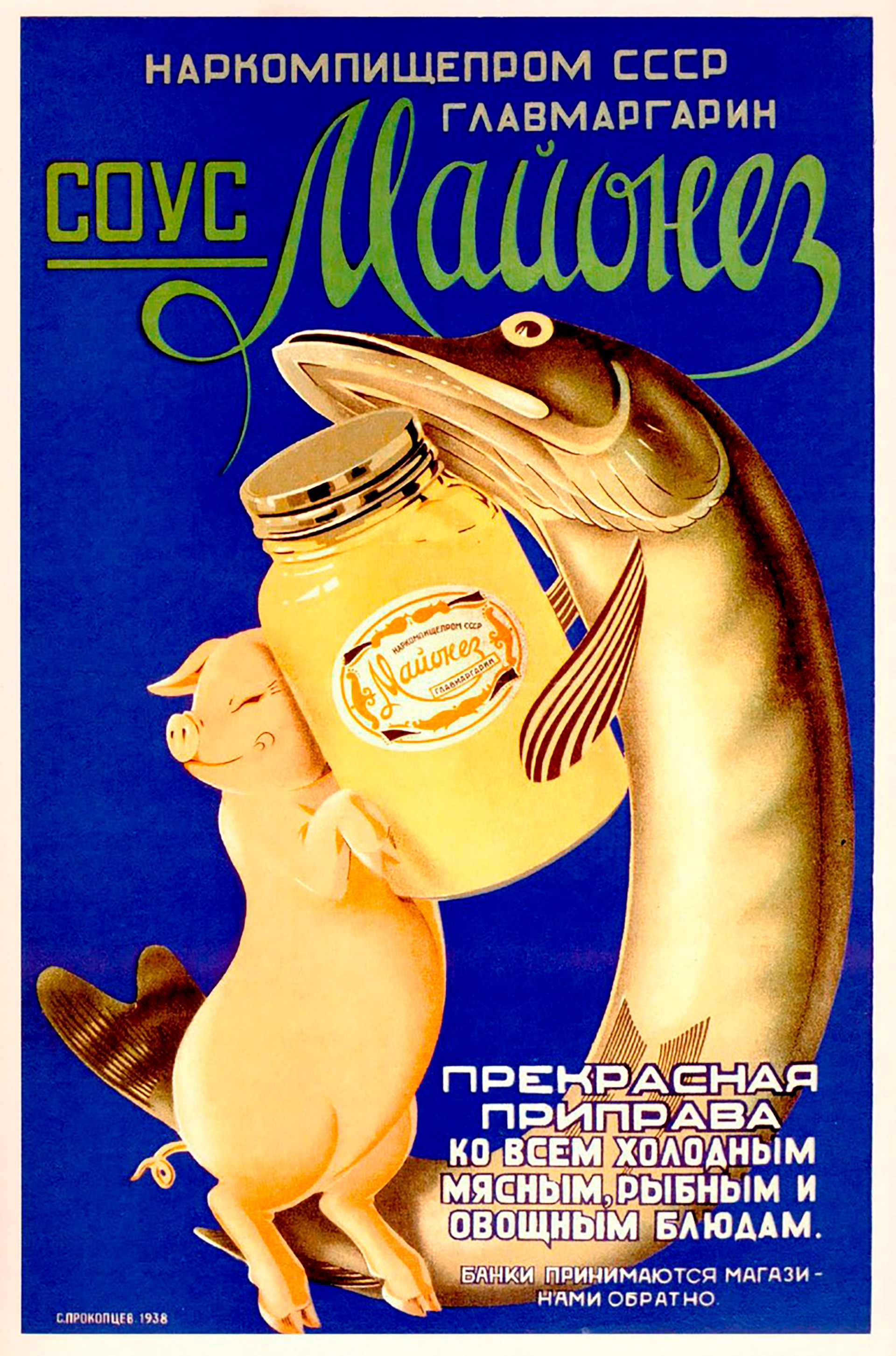

Passion for mayo

Today mayonnaise is not considered healthy. But in the early Soviet years, when there was lack of nourishing food, it was a valuable source of calories and fat. Moreover, mayonnaise made any food rather tasty. People used to say that it was possible to eat anything as long as it was slathered in mayonnaise. Soviets hunted for this white sauce endlessly, especially because there were hardly any other sauces available. Soviet mayonnaise, which appeared in 1936, only vaguely resembled its French counterpart. The recipe included refined oil, fresh egg yolks, mustard, sugar, vinegar, salt, and spices - no E-additives and stabilizers. Mayonnaise was in short supply so many Soviets only got to eat it during holidays.

The Soviet advertising poster.

Archive PhotoMayonnaise is the basis for the three pillars of the Soviet holiday table – Olivier, “fur coat” and “mimosa.” It’s also used in a pork dish called “French meat,” although no such dish ever existed in France of course. Mayonnaise is added to the dough (cookies made from mayonnaise using a meat grinder anyone?). By the way, the empty jar of mayonnaise was not thrown out: It was often used as a container for medical supplies.

Nostalgia for the Soviet kitchen

The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 but still continues to influence the tastes of Russians. Eating habits may have become healthier since then but every Russian will tell you - there’s always a craving for mayonnaise deep down, preferably slathered over salads and breaded cutlets.

Inside the Varenichnaya cafe.

Maria Ionova-GribinaDespite the fact that there are a lot of restaurants serving traditional and modern Russian cuisine, Soviet canteens still trigger bouts of nostalgia. Restaurants in the Soviet style are very popular not only among Russians but also among tourists, and many people still cannot imagine the New Year table without the Olivier salad.

Do you remember the milky taste of Soviet ice-cream? Read this story to find out why this delicious dessert was the best!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox